On the morning of March 15, amid escalating fears about the COVID-19 outbreak, a 62-year-old educational consultant showed up at the John F. Kennedy International Airport in New York for a flight to Trinidad, where he planned to attend a funeral, he said. But police stopped the consultant at the gate and arrested him under a year-old warrant, alleging he’d given bogus information for a state identification card in New Jersey.

The arrest led the consultant into New York‘s notoriously brutal and unsanitary jail system, where COVID-19 was beginning to spread.

The consultant, who spoke on condition that he be identified only by his first name, Bill, knew jail would be terrible. But he said he was shaken by an apparent lack of protection against the coronavirus for inmates and workers.

His first night in the Vernon C. Bain Center, a floating jail in the East River, was spent on a floor, lying back-to-back with other men, “like a slave ship,” he said. Then he was assigned to a dorm at the floating jail where inmates — many of them charged with nonviolent crimes or parole violations — bunked about 3 feet apart, ate at communal tables, shared toilets, showers and phones and had soap but no masks, disinfectant or alcohol wipes to keep their detention space clean, he said. New inmates arrived, others left. Corrections officers guarded them without much protective gear beyond gloves. They tracked news of the virus’ spread on the day-room television.

“We were left to our own defenses,” Bill recalled. “We didn’t know what was going to happen to us with the virus. We were in cramped quarters where no one really cared.”

That sense of being stalked by a deadly disease without being able to defend against it pervades New York City jails, according to inmates, reform advocates, defense lawyers, health officials and the union representing corrections officers. So far, 167 inmates and 114 Department of Correction staff members have tested positive for COVID-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus, signs that it is being transmitted inside facilities and following those who are infected as they return to outside communities.

Do you have a story to share about how the coronavirus is affecting the criminal justice system? Contact us

The experience in New York, which is the center of the American outbreak with more than 36,000 cases as of Monday, could replay in cities and counties across the country, public health experts say. Jails may act as COVID-19 incubators, sickening and killing inmates and workers and spreading the disease to the broader public.

“They're all ticking time bombs,” said James Manfre, a former sheriff in Flagler County, Florida, and a member of the Law Enforcement Action Partnership, a nonprofit that advocates for the reduction of jail and prison populations. “County jails will suffer the most because they’re the ones that cycle people in and out the quickest.”

There are indications that COVID-19 is beginning to spread in lockups around the country. Jail inmates have tested positive in Illinois, New Jersey, California, Texas, Louisiana, Georgia, South Dakota and Washington, D.C. Inmates or staff members have tested positive at state prisons in California, Louisiana, Michigan, Texas, New York and Georgia. The federal Bureau of Prisons says 19 inmates and 19 staff members have tested positive; one inmate has died.

Authorities in many parts of the country are scrambling to respond, cutting down on arrests, suspending trials and court hearings, banning jail visits, screening staff as they come to work, isolating ill inmates and releasing detainees deemed low risk to the public.

Full coverage of the coronavirus outbreak

Los Angeles County, which has America’s largest jail system, says it has no confirmed COVID-19 cases behind bars, but has released 1,700 inmates to try to prevent a spread. In Cook County, Illinois, which includes Chicago, 24 inmates and nine workers have tested positive as authorities work to release detainees accused of low-level crimes. New Jersey, South Carolina, Iowa, Nashville, Tennessee, and Cuyahoga County, Ohio, have made similar moves.

Attorney General William Barr has ordered the Bureau of Prisons to allow more offenders to serve time in home confinement, but inmate advocates and some Congress members want the Department of Justice to do more, including expanding the release of elderly and ill inmates.

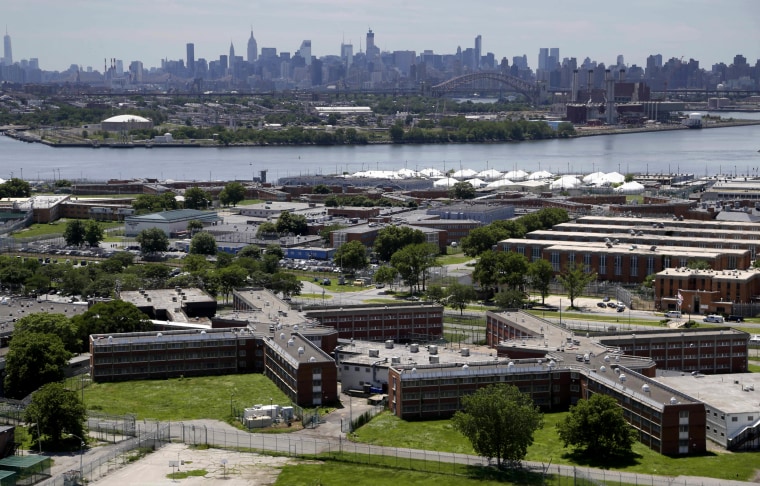

In New York City, Mayor Bill de Blasio has ordered the release of 75 jail inmates nearing the end of their sentences for nonviolent offenses, and has said he wants to release about 300 more. But that’s a small fraction of the 4,636 inmates in the city’s jails, 3,000 of whom are waiting for trial and 1,300 of whom are being held for violations of parole or probation. The city’s Board of Correction, which monitors jail conditions, has implored authorities to release more than 2,000 inmates who are elderly, ill or accused of nonviolent offenses.

Last week, New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo, a Democrat, said he would approve the release of 1,100 jail inmates held on alleged parole violations, a number that would likely include a few hundred in New York City. On Friday, the Legal Aid Society said it has persuaded a judge to order the release of 106 accused of minor violations of parole.

“It’s important for everyone to realize they are not separate from the community. We are all together. But they don’t have a chance because they are locked up in crowded, dirty conditions and that puts everyone at risk,” said Dr. Robert Cohen, a member of the board who ran medical services on Rikers Island, the city’s main jail complex, during the AIDS crisis. “Wherever possible, the number of people should be cut down to decrease the risk to people working and living in jail. It’s a public health action that will save lives.”

Michael Skelly, spokesman for the New York City Correction Officers’ Benevolent Association, which represents jail guards, said the city took too long to shut down in-person inmate visits, increase segregation of at-risk inmates and supply staff with enough gloves, masks and hand sanitizer. The focus on releasing inmates has overshadowed the plight of corrections officers, he said.

“We’re at the epicenter of the epicenter,” Skelly said. “You want to talk about social distancing, but you have housing areas in jails that are 50 inmates to one officer, or almost 100 to one.”

Some inmates said in interviews that they felt for the officers who guarded them.

“The officers are terrified,” one man locked up on an alleged parole violation said in a brief phone interview from a dormitory-style detention center on Rikers Island. He spoke on condition of anonymity out of fear that it could jeopardize his case. “They’re more sympathetic to us. They look at it as we’re in it together.”

The New York City Department of Correction, which runs the city’s jails, said in a statement that it is taking a number of steps to protect workers and inmates, including screenings, “robust sanitation protocols,” promoting social distancing and handing out soap and cleaning supplies. The agency also said it was trying to space out dormitory sleeping assignments, or have inmates sleep “head-to-toe.”

“The health and well-being of our personnel and people in custody is our top priority,” the department said in a statement.

But Kelsey De Avila, head of jail services at Brooklyn Defender Services, a public defender agency, said the city’s responses were inadequate.

“We are running against the clock,” she said. “Our health care system is already overwhelmed and it’s going to get worse in coming days and weeks and we could really help ease that burden by not putting people in jails who’ll be exposed to the virus.”

Another Rikers inmate, who asked to be identified only by his first name, Tyrell, said he has watched several other men fall ill and be removed from his dormitory without any explanation. New inmates have been assigned the empty beds with little apparent cleaning, he said.

“I fear for my life,” Tyrell, 30, who is being held on a parole violation, said. “I don’t want to catch coronavirus. I came here healthy and I don’t want to leave here with it.”

Download the NBC News app for full coverage of the coronavirus outbreak

Junior Wilson, 57, in Rikers for an alleged grand larceny and parole violation, said the mood had turned dismal.

“They’re not giving us hardly anything to clean with, the bare minimum. Little spray bottles to spray this or that down,” Watson said. “It’s just ridiculous. They’re slowly killing us in here.”

Bill, the educational consultant, considers himself lucky. A divorced former lawyer who lives paycheck to paycheck, he spent six days stuck in the floating jail while Legal Aid Society lawyers tried to persuade prosecutors to release him — along with dozens of other people accused of low-level crimes. He was let go after New Jersey prosecutors said that, because of the coronavirus’ impact on the court system, they’d dropped their request to have him extradited from New York.

Bill said he has been feeling ill since his March 20 release, and has been self-isolating at home in New Jersey. He’s also thinking of those who remain in jail.

“There was a lot of uncertainty and fear,” he said. “We were told to wash our hands and to avoid contact with each other but the reality was that there was no prevention whatsoever. There was nothing being done to protect us.”