DENVER — A plan to help homeless people during the pandemic by letting them set up camp in a church parking lot has forced residents in an affluent neighborhood to question their progressive values and commitment to helping ease social ills.

Advocates said unsheltered people were being left behind in Covid-19 mitigation efforts, so they devised a plan to provide safe outdoor spaces where homeless people could access meals, medical care and other services.

But when Pastor Nathan Adams of Park Hill United Methodist Church announced on Easter Sunday that it would put faith into action and create a camp on site for about 40 unsheltered people for six months, many residents in the community were unsettled.

“When I bought in Park Hill, it wasn't because there was a homeless encampment one block from my front door,” said Jon Kinning, who lives a block away from the church. “If I wanted to live in downtown Denver and near homelessness in my face every day, having people sleep on my patio or go to the bathroom on my garage, I would live downtown.”

About 4 1/2 miles from downtown, Park Hill is full of flowering trees, stately brick homes and cozy bungalows. Black Lives Matter signs adorn front lawns in the largely white neighborhood surrounding the church, and in the 2020 election, about 67 percent of voters in Park Hill cast ballots for Joe Biden.

“It's a neighborhood where kids are used to being pretty free,” said Stephen Booth-Nadav, who has lived across the street from the church for 20 years. “In the summer, kids are out playing in the street, playing in the parking lot, up and down the sidewalks, playing with their dogs.”

When members of the church approached the Colorado Village Collaborative about transforming the lot into a safe outdoor space, Adams and many of the 400 people on an informational call were supportive. Two such camps had already opened in December near the state Capitol downtown without any major problems.

“We see this as an extension of the work that God is calling us to do, love our neighbors but specifically to love our most vulnerable neighbors," Adams said recently. "In this case, those that are experiencing homelessness."

Despite the call to action, five Park Hill residents filed a lawsuit earlier this month in Denver District Court to stop the encampment and sought a temporary restraining order to prevent the project from moving forward.

They said in the lawsuit that the proposal "pose[s] a real danger to minors and school-aged children," does not address the impact on the neighborhood and displaces people from one part of the city "with available resources to an area not equipped to handle" the safe-camping site.

The lawsuit was dismissed by the court Wednesday, and the Colorado Village Collaborative is on track to open the camp June 14 after securing a city permit.

Cole Chandler, executive director of the collaborative, which has created tiny home villages for homeless people in Denver, said more people are sleeping outside rather than in emergency shelters to avoid catching Covid-19, to have more freedom and to avoid becoming crime victims in the crowded spaces.

“We're seeing some of the greatest numbers of homelessness that we've seen since the Great Depression," Chandler said recently. "And there are not enough places for people to go. We need solutions like this that seek to mitigate harm, seek to reduce impacts in surrounding neighborhoods and, most importantly, seek to provide services and long-term housing connections to people on the streets.”

A point-in-time survey conducted in January 2020 by the Metro Denver Homeless Initiative found 4,171 people living on the streets in the city and county. City shelters can house about half that many each night. Results from this year's survey are not out yet, but experts expect the number to grow.

Daniel Brisson, executive director of the Center for Housing and Homelessness Research at the University of Denver, said innovations like the parking lot encampment are key to easing the crisis.

“There's just not enough beds in the current sheltering system to meet all the needs, so we need different solutions for the different people experiencing homelessness,” he said.

Yet Booth-Nadav's daughter, Ariella Nadav, 18, said she will fear for her safety when she gets home from work late at night and has to park on the street.

"I don't want to walk into my house every night over the summer and be scared for my life, and not just my life, but my well-being," she said. "I don't want to have to deal with getting sexually harassed every day."

No violent or sexual offenders are allowed in the camps, Cole said. But the population includes people who have been on the streets for years and have addictions.

"We don't exclude chronically homeless. Our site currently is about 40% people that are newly homeless and 60% that are chronically homeless," he said. "We don't allow drugs or substances at the site. But this is a harm-reduction model. And we do certainly have people that are living with an addiction that are a part of this community."

On a recent tour of one of the collaborative's camps downtown, a drug deal could be seen happening across the street near an abandoned diner.

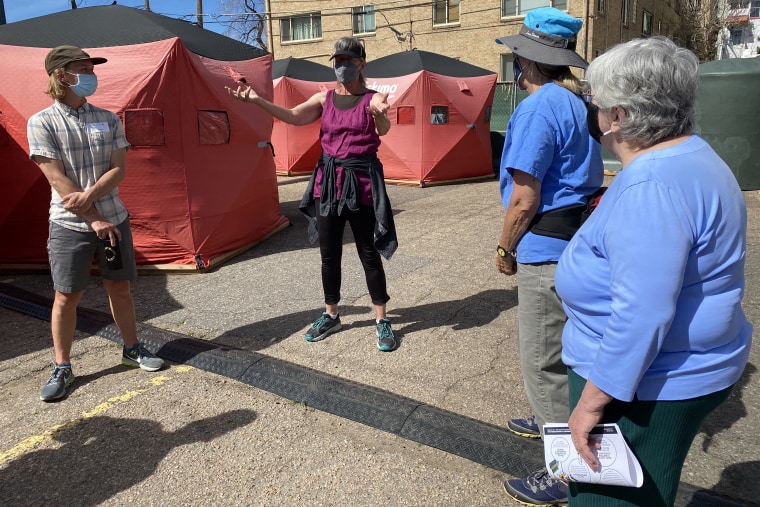

Cole was showing Park Hill residents around to help ease their anxiety about what a camp would look like in their neighborhood. Colorful outdoor fencing kept the encampment private, and bright red tents outfitted with electrical power for fans and heat were lined up in neat rows. Portable showers and toilets were positioned nearby, along with hand-washing stations and trash cans.

The grounds were clean, and security guards and volunteers were on duty 24/7. Cole said no one in the Capitol Hill camp has tested positive for Covid-19, and 32 out of the 36 residents were vaccinated.

Mark Montes, known as “Shorty,” was helping himself to coffee inside a tent that served drinks and snacks.

“I was homeless 11 years on the streets,” he said. “If it wasn’t for them, I’d probably still be on the street drinking and not even getting a job or anything.”

Another resident who identified himself only as Max was wearing a sunny yellow dress, a wide-brim hat and flip flops as he sat under a tent with his camp neighbors and a dog named Muttley.

“I’m homosexual and my family doesn’t approve,” Max said, adding that he feels much safer in the camp than in a shelter or on the streets. “Getting woken by, getting kicked in the head by a cop is not the best thing.”

Even after seeing the Capitol Hill camp, Stephen Booth-Nadav is unconvinced.

“I've read stuff on Facebook that some of my neighbors five blocks away are saying, oh, they're so happy that this is coming to Park Hill,” he said. “I'm thinking, five blocks away, I might say that, too. Does my neighbor five blocks away understand what I'm saying when I say my daughter's afraid to park her car and come into the house?”

But Brisson said that kind of attitude prevents reforms from taking hold.

“To say that it 'shouldn't be me' pushes it on the least advantaged, the most disadvantaged neighborhoods in our community,” he said. “So I would really, really invite people in the community who feel like, 'My neighborhood isn't the right place for this,' to rethink: Whose neighborhood is?”