This article has been jointly published by NBCNews.com and InsideClimate News, a nonprofit, independent news outlet that covers climate, energy and the environment.

PORTSMOUTH, Va. — At the foot of the Chesapeake Bay in southeast Virginia lies a Naval shipyard older than the nation itself. One of the country’s first warships was built here in 1799. So was the first battleship, and decades later the first aircraft carrier.

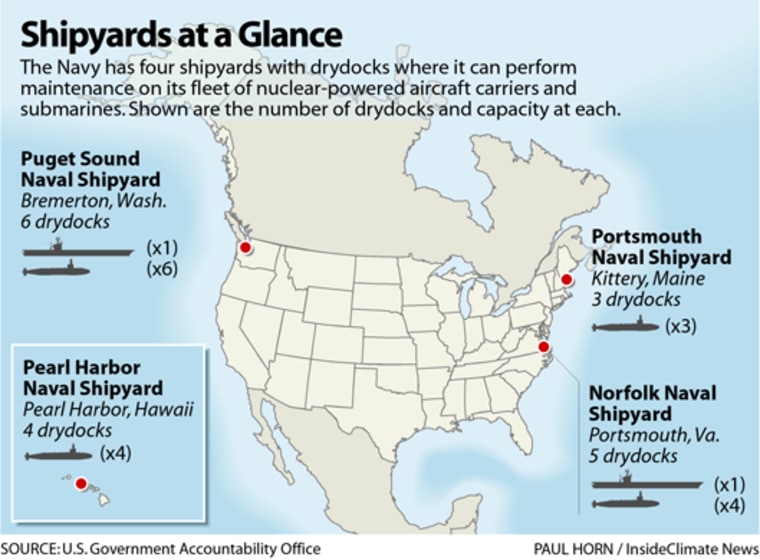

Over the past three centuries, Norfolk Naval Shipyard has been blockaded and burned to the ground, only to be rebuilt again and again. Today, it’s one of four Navy shipyards that maintain the nation’s nuclear-powered submarines and aircraft carriers, which enable the Pentagon to respond quickly to military and humanitarian crises across the globe.

But the shipyard now faces its greatest existential threat: rising seas and extreme weather driven by climate change.

In the past 10 years, Norfolk Naval Shipyard has suffered nine major floods that have damaged equipment used to repair ships, and the flooding is worsening, according to the Navy. In 2016, rain from Hurricane Matthew left 2 feet of water in one building, requiring nearly $1.2 million in repairs.

And that wasn’t even a direct hit — the most immediate worry, former military leaders say, is a strong storm that blows right through the area.

“It would have the potential for serious, if not catastrophic damage, and it would certainly put the shipyard out of business for some amount of time,” said Ray Mabus, who was the Navy secretary under President Barack Obama. “That has implications not just for the shipyard, but for us, for the Navy.”

Among the shipyard’s greatest vulnerabilities are its five dry docks, which are waterside basins that can be sealed and pumped dry to expose a ship’s hull for repairs. Once inside, vessels are often cut open, leaving expensive mechanical systems vulnerable to damage from storms and flooding.

The dry docks “were not designed to accommodate the threats” of rising seas and stronger storms, according to a 2017 report by the Government Accountability Office. Navy officials warned the government watchdog agency that flooding in a dry dock could cause “catastrophic damage to the ships.”

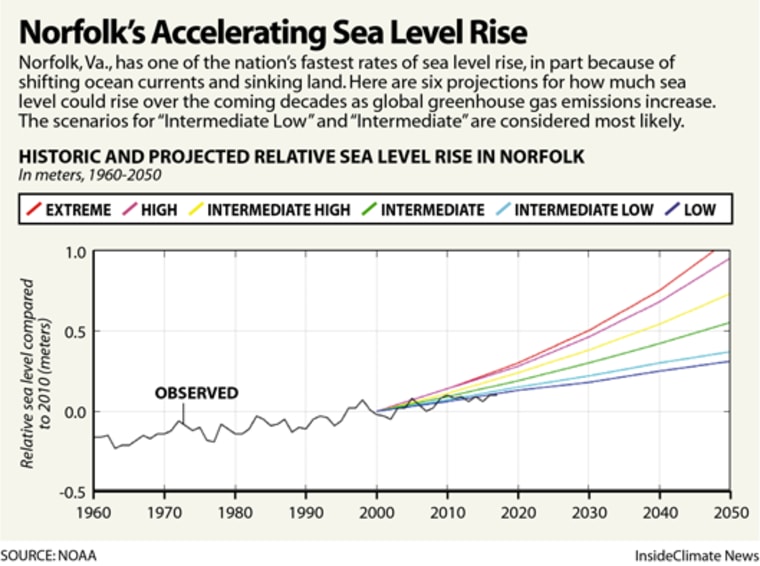

Already, high-tide flooding is contributing to extensive delays in ship repairs, the GAO said, disrupting maintenance schedules throughout the Navy’s fleet. Sea level in Norfolk has risen 1.5 feet in the past century, twice the global average, in part because the coastline is sinking.

The Navy has erected temporary flood walls and uses thousands of sandbags to protect the dry docks at Norfolk Naval Shipyard. The Navy has also begun elevating some equipment, but the facility remains vulnerable, according to a Defense Department survey on the effects of extreme weather on military bases, obtained through a public records request. In response, the Navy proposed a more permanent barrier estimated to cost more than $30 million, part of a 20-year, $21 billion plan submitted to Congress this year to modernize Norfolk as well as Navy shipyards in Maine, Washington and Hawaii.

But the new projects have yet to be approved.

The Navy said it takes extensive measures to limit damage from flooding. “These requirements ensure the safety of our personnel, our ships (nuclear and non-nuclear), and shipyard infrastructure," William M. Couch, a Navy spokesman, said in an email.

In October, Hurricane Michael offered a glimpse of what can happen to coastal military bases in a storm’s path when it leveled much of Tyndall Air Force Base, damaging more than a dozen stealth fighters undergoing maintenance.

Months earlier, the Federal Emergency Management Agency envisioned what might occur if a similar storm were to strike Norfolk — by driving a computer-simulated Category 4 hurricane directly into the region as part of a national disaster preparedness drill. Their simulated cyclone’s 140-mph winds snapped power lines and cell towers, hobbling the grid and communications, and whipped the Chesapeake Bay into a 12-to-15-foot storm surge, high enough to flood the downtowns of nearby cities.

The Navy declined to disclose the precise damage to the shipyard in the scenario, but a news release described the aftermath as “New Orleans without the levee system.” National hazard maps show a storm of that magnitude would likely submerge the entire facility.

“It’s not a question of if, it’s a question of when,” said retired Vice Adm. Dennis V. McGinn, who was assistant secretary of the Navy for energy, installations and environment until January 2017. “And when it hits, how vulnerable are we going to be, and are we going to be standing there saying, ‘oh, we woulda, coulda, shoulda?’”

Limited time, little progress

The Navy has long understood the stakes of global warming. It has many coastal facilities, and its forces are often first on the scene of humanitarian emergencies triggered by extreme weather.

A decade ago, the Navy commissioned the National Research Council to study the risks climate change poses to its ability to respond to these crises and keep the country safe. The 2011 report said a thawing Arctic would stress the military’s fleet by opening a vast new arena to police in particularly harsh conditions. The report also found that 56 Naval facilities worth a combined $100 billion would be threatened if sea level rose about 3 feet.

"Every year you wait to make decisions and take actions, the risk goes up."

The report warned that the Navy needed to begin protecting the most vulnerable facilities immediately, and had only 10 to 20 years to begin work on the rest. Seven years later, there’s been little progress, said retired Rear Adm. Jonathan White, who led the Navy’s Task Force Climate Change before retiring in 2015.

“Many of those recommendations, most if not all, have gone unanswered,” he said. “Every year you wait to make decisions and take actions, the risk goes up. And I think the expense also goes up.”

Across the military, the response to climate change has been piecemeal and inadequate, according to interviews with more than a dozen retired officers and former senior-ranking national security officials.

“It’s probably on the radar, but it’s below what we would call the cut line,” said retired Rear Adm. David W. Titley, who initiated the Navy’s Task Force Climate Change in 2009. Senior officers spend their days fielding urgent requests for money and resources, he said, and have little left for long-term threats. “That’s probably how it’s looked at: ‘Yes this is a problem, but I still see the shipyard out there,’ and so it gets kicked down the road.”

The Navy has begun protecting bases here and there, elevating critical equipment like generators and creating “micro-grids” at some facilities to make electrical supply more resilient to storms. And perhaps most critically, Congress passed legislation this year requiring any military construction in a 100-year floodplain be elevated at least 2 feet above the expected flood level.

But even if some of the work the Navy plans to undertake receives funding, it may be inadequate. A flood wall to protect the most vulnerable dry docks at Norfolk Naval Shipyard, for example, will not be built to the more stringent standards once considered — the so-called 500-year flood, with only a 0.2 percent chance of occuring in any year. Instead, it’s a foot and a half lower, designed to protect against a 100-year flood, which probably isn’t enough to prevent flooding in a Category 4 hurricane. Climate change is already making severe storms more frequent, and a few decades from now, when the seas will be 1 or 2 feet higher, a smaller storm would inflict the same amount of damage.

Managing climate change under Trump

Even when commanders take climate change seriously, politics and legislative gridlock can block funding. “My experience was, the thing that Congress is most likely to do is not fund it until it becomes a crisis,” said Mabus, the former Navy secretary. “And then it might be too late.”

Addressing climate change has become more difficult under President Donald Trump, who said recently that he thought climate scientists had a political agenda. His administration omitted climate change in its first National Security Strategy, and he rescinded an Obama executive order that sought to provide intelligence analysts with current climate science to better monitor global hotspots.

In this environment, military officials have become reluctant to work openly on climate change, said Joan VanDervort, former deputy director for Ranges, Sea and Airspace at the Pentagon. “They try to stay away from the words ‘climate change,’ and use words like ‘natural resources’ and ‘resiliency’ and terms like ‘weather,’ ‘hurricanes,’” she said. When you omit “climate change as a priority related to our national security,” she added, “it’s very difficult to get funding.”

When asked about the Navy’s response to climate change at the shipyards, a spokesman pointed to comments Defense Secretary James Mattis made last year: “The Department should be prepared to mitigate any consequences of a changing climate, including ensuring that our shipyards and installations will continue to function as required.”

Navy officials declined to be interviewed. In emails, Couch said that "flooding concerns were a major consideration for Norfolk Naval Shipyard in evaluating necessary work," and that the Navy has "identified some near-term projects that mitigate concerns related to rising seas and flooding," including raising equipment and building flood walls.

Like sinking a ship

All of the nation’s 69 submarines and 11 aircraft carriers are nuclear-powered. They help project the military’s might across the globe, but nuclear power has a drawback: The ships can be repaired at only a handful of facilities with the equipment and personnel to handle radiological material. Of the Navy’s four shipyards, only two can dry-dock aircraft carriers: Puget Sound in Washington state and Norfolk.

In two reports — from 2014 and last year — the GAO cited officials at Norfolk and an unnamed shipyard who warned that flooding from storms posed a threat to ships undergoing maintenance. In one case, they were preparing to cut a submarine in half and were concerned that “if salt water was allowed to flood the submarine’s systems, it could result in severe damage.”

The Navy explained in an email that it has measures to prevent that type of accident. When a major storm is approaching, it said, workers can quickly seal up ships undergoing repairs, allowing them to refill the dry dock and float the vessel.

That’s what the shipyard did to the submarine USS Wyoming as Hurricane Florence headed toward Norfolk in September, the Navy said.

Florence veered into the Carolinas, sparing Norfolk.

But recent flooding has worsened already poor conditions at Norfolk, the GAO said. Most capital equipment infrastructure at the shipyards, such as cranes and other core machinery, is beyond its effective service life and obsolete, according to a Navy report provided to Congress this year. The shipyards have suffered extensive maintenance delays because of deteriorating conditions and other factors, with nearly 14,000 lost days of operations for the submarines and aircraft carriers between 2000 and 2016, according to the GAO.

Mabus, the former Navy secretary, said these delays ripple throughout the fleet’s carefully choreographed maintenance schedule, which means ships may not be ready when they’re needed. “It’s a very, very serious readiness issue,” he said.

Without a tremendous investment in protections, Mabus and others said, the Pentagon will have to hope that disaster does not strike. Hurricane season is nearly over, but nor’easters can bring storm surges just as high.