MODOC, Indiana — When Jamie Harshman entered kindergarten at the local public school here more than 20 years ago, her parents did not anticipate that she would graduate from Union School Corp., as the single school in this district has been known since it was formed in 1952.

Locals have long thought that the small rural school district would eventually be shut down and absorbed by one of the neighboring districts. After all, only a few hundred students ranging from kindergarten to 12th grade were enrolled in the school, situated in this town of 190.

“That impending doom has been here for a long time,” said Harshman, who now serves as the curriculum director for Union School Corp. and spends her days working from its central office.

But the fear for Union’s survival has largely disappeared since last year, when it began working with a private education corporation to open a digital school, in which kids at home join classes taught live by teachers online. That partnership with K12 Inc. has increased enrollment numbers and, as a result, the amount of state dollars they receive.

But now a discussion is brewing outside of Modoc and its small school district. Advocates call the virtual school an innovation that rescued a cash-strapped small public school and offers increasingly rare learning opportunities to rural students. Critics call it a devil’s bargain that forced a school to trade academic oversight and accountability for dollars that mostly go to a private corporation.

Students and parents, meanwhile, are left somewhere in the middle. And now the Board of Education has formed a committee to inspect the virtual schools — all of which were considered failing by state standards last year — after Gov. Eric Holcomb, a Republican, called for “immediate attention and action” to address the problem.

It might seem odd for a tiny rural school nestled here between huge tracts of farmland to have a digital school with more than 700 students who live across the state. But, as school board vice president Christa Ellis explained, the district was in debt and out of options.

For years, members of the public argued whether to shutter the school or keep it open. Board meetings moved to the cafeteria to accommodate interested locals, and Harshman said there are some friends she doesn't speak to anymore because of how heated those discussions became.

Some like Ellis worried closing the school would mean the end of the nearby communities — most so small they don't have a single stoplight — and force kids to travel farther to larger schools.

“When you eliminate the school, we’ve seen what happens to these small towns,” said Ellis. “Those towns have died over the years. We didn’t want our entire township and [nearby townships] to die. We didn’t want our community to die.”

So last summer the school board decided to partner with the private education corporation known as K12 Inc. — which had a 2017 revenue that exceeded $875 million — to open a public virtual school called Indiana Digital Learning School. It has grown Union’s enrollment from 256 students in 2016-17 to 937 students in 2017-18, according to Indiana’s Department of Education.

And in Indiana, where the state allocates $5,273 to each student, that’s millions of taxpayer dollars flowing to Modoc.

But much of that money appears to flow right back out, according to the contract between Union School Corp. and K12 Inc. Union only retains 5 percent of those dollars, while K12 takes 95 percent to operate the school and add to their bottom line.

A devil’s bargain?

K12 Inc. called Union’s Superintendent Allen Hayne in the summer of 2017 after he interviewed for a job at their organization — a post he did not receive — and approached him with the idea of a large digital school.

Prior to that, the school district’s most profitable move was to add an international program that brought in kids from China for $18,000 a pop, and they even reached out to the nearby Amish community, adding a total of 14 Amish students. Other ideas included advertising the school at a nearby town's Walmart or getting a billboard.

“We’ve almost kind of been forced to run our school more like a business in terms of marketing ourselves and bringing in new kids to stay afloat,” admitted Hayne, who served as superintendent and high school principal simultaneously. “And we just found an out-of-the-box idea that really works for us and has generated enough kids and interest to keep us open.”

Three weeks after the school board approved the decision to partner with K12 and just about 12 days before the start of the school year, Union appointed Elizabeth Sliger as the head of Indiana Digital Learning School (INDLS), who previously worked for K12 in Dayton, Ohio, and remains a company employee.

The entire digital school operates with five full-time employees who are split between two former classrooms that K12 rents from Union for $1,200 a month. It has 21 teachers on staff, holds around 66 classes each day, and has an enrollment capped this past year at 740 students by the school board because they wouldn’t receive additional funding from the state if they added more students after October.

Teachers work out of their homes and are hired and fired by K12, so they don't receive the same retirement benefits as public school teachers. Diane Smith, who lives outside of Columbus, Indiana, came to INDLS after she quit her public school job when her mother was sick. She said she enjoys the work.

"I have about 10 minutes before each class and since they’re all the same, the prep time is pretty easy. All of the curriculum they have here meets state standards, so I feel pretty comfortable with it," said Smith, who teaches a computer course via a headset and a laptop — often with one of her three Yorkshire terriers on her lap.

Hundreds of Indiana kids are currently on a waiting list for enrollment in INDLS, and many intrigued families attended the numerous "EnRolling Skate Events" K12 put on throughout the state during the month of May. Nearly 40 people registered for the event in Bloomington, Indiana, and children and parents met, skated and chatted about school as pop music blared.

Now Union and INDLS project they’ll have more than a thousand virtual students next year after they release their cap.

Public school advocates are concerned that the district is acting out of a sense of desperation for dollars because consolidation is on the horizon for so many rural schools. Underlying these criticisms is a belief that the small, rural school district is being taken advantage of by a large private corporation.

“It’s a moral hazard issue — a devil’s bargain,” Preston Green, a professor of education leadership and law at the University of Connecticut, said after reviewing the contract between the school and K12. “These districts need the money, are responsible for these students but the students are not a part of them. The question becomes: How concerned is the district going to be? It just doesn’t have the incentive to focus on these students. They’re just dollars to them.”

Union and INDLS reject the characterization.

“As a school, I’m not being taken advantage of,” Hayne told NBC News. “You know, I really don’t believe that ... with all the things they do, I feel very comfortable in the agreement.”

K12 Inc. said these agreements usually use 80 percent of those state dollars for operation costs, but noted that there are additional costs and that ultimately the company typically makes a 3 percent operating profit.

Another concern is that one of K12 Inc.’s Hoosier Academies Virtual School closed after receiving an F from the state every year from 2010 to 2016. The school also suffered high student turnover and ultimately dropped its enrollment from more than 3,000 students to 1,750 this past year.

Union School Corp. said they were unconcerned about that and a report from the National Education Policy Center concluded that district-operated virtual schools fare much better than charter-operated schools. However, it remains to be seen whether a small district like Union has the bandwidth to provide proper oversight and hold INDLS accountable.

As of now, it appears to run fairly independently within Union.

“There was a great deal of care put in to make sure that any mistakes made in the past wouldn’t be made with this new school,” Ellis said of INDLS.

Lawmakers, however, are worried about how many virtual schools are failing standards across the state. Digital schools in Indiana boast graduation rates far lower than the state average of more than 80 percent — one popular program even had a graduation rate of 6.5 percent or 64 students out of 985.

That’s a trend that tracks nationwide, as only 36.4 percent of full-time virtual schools across the country received acceptable performance ratings, according to the National Education Policy Center report.

An opportunity to learn safely

For some, however, this new digital school has been a godsend.

The worst of A.J. Besson’s seizures caused him to break his nose at the local school in Wheatfield, Indiana, this past year. His mom, Candida York, 47, pulled him out of class as she looked for an education alternative.

A.J., 8, was born 10 weeks early and was diagnosed with periventricular leukomalacia, a white matter brain injury that can cause seizures and learning disabilities — A.J. has attention deficit disorder and obsessive compulsive disorder.

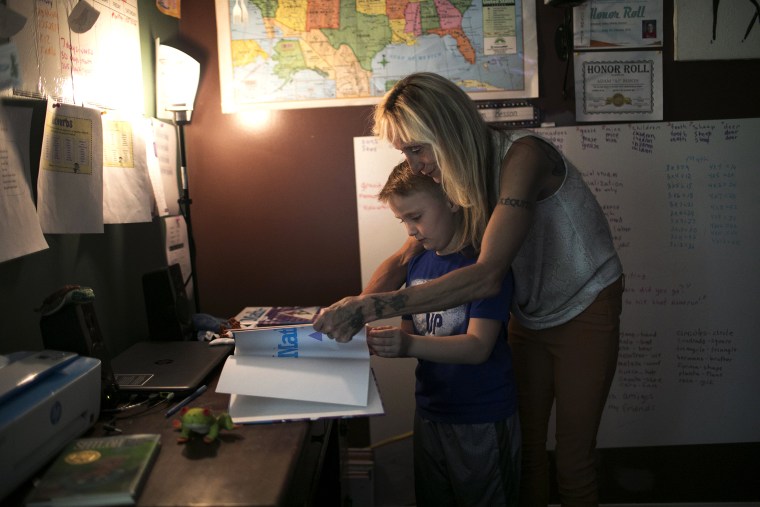

Soon she enrolled him in Indiana Digital Learning School, based in Union School Corp. nearly 200 miles to the southeast of their home in Wheatfield, Indiana. She says he has thrived.

“They saved my son’s life and they saved my family,” York said amid tears. In her living room, a whiteboard on one wall is covered in her son’s vocabulary words and an honor roll certificate bears his name.

Laying on a trampoline in the middle of the room, A.J. agreed.

“It’s great that I don’t have seizures anymore,” said A.J., who uses the trampoline to exert unused energy during his school day. “My mom said if I had too many seizures that I would have died. I kept having seizure after seizure at school.”

Many INDLS students have similar stories. Sliger said that while nearly 20 percent of their students require special education, more than 40 percent use the word “bullying” when explaining why they came to the program.

But that doesn’t mean these programs shouldn’t be held to high standards, some say.

“If they are the most vulnerable or this is the student’s last chance, then we should be doing even more to help them rather than accepting substandard performance,” said Gordon Hendry, a member of the state board of education overseeing the committee looking into virtual schools.

Sliger said she’s not intimidated by that mandate, but she said she hoped that the state would remain aware that her student body is atypical for its level of achievement and home life.

“I expect to meet high standards,” she said. “I don’t need you to lower any bars. But I am gonna do it for students who are different and you need to listen to those students’ needs.”

Though virtual schools in the state are failing, Sliger is sure that her new school, which hasn’t yet received a grade, will do better than any of the others.

Union certainly expects that it will be doing well. They’re already replacing the school’s HVAC system and redoing the track. Teachers are making plans to stay in the area, rather than looking for jobs ahead of what felt like imminent closure. Students in Union’s physical school can now take a Spanish class through INDLS and have the opportunity for new course offerings that their rural school could not provide before.

“Those rumors of consolidation are gone,” said Union High School Principal Michael Huber. And that’s “because of the stability that this program has provided the brick and mortar school.”