March 30 was a meaningful day for Arlene Van Dyk. The longtime intensive care unit nurse at the Holy Name Medical Center in Teaneck, New Jersey, got to see a patient leave the ICU — a woman who’d contracted the coronavirus and spent 10 days on a ventilator.

She wasn’t just any patient, Van Dyk said. This was the first COVID-19 positive person at Holy Name to be removed from life support and prepared for discharge.

“For us in the ICU, we see the sickest of the sick,” Van Dyk, a single mother of two, said. “We forget that there’s people that do well. This was a huge thing for us to see this.”

The acute care facility has had an up-close view of the daily tragedies unfolding across the region in recent weeks. Bergen County, where the hospital is located, has experienced 263 deaths and more than 7,500 confirmed cases of COVID-19, according to the New Jersey Department of Health. In New Jersey, as of Tuesday, there were more than 44,000 confirmed cases and more than 1,200 deaths and across the Hudson River in New York City, there have been nearly 77,000 cases and more than 4,000 deaths as of Tuesday, according to Johns Hopkins University.

Holy Name reported 11 cases of the disease in mid-March, with six of them in its intensive care unit, hospital spokeswoman Jessica Griffin said. By Tuesday, those numbers have swelled: more than half of the 2,300 tests its staff conducted yielded positive results, 183 people were hospitalized and 57 died.

The hospital suffered its own losses. A sterile supply technician, Severiana Gimenez, died from complications of COVID-19 on March 29. Five days later, so did Jesus Villaluz, who spent 27 years working in patient transport.

Twelve doctors have contracted the virus, Griffin said. The hospital’s CEO, Michael Maron, was also sickened by it. Maron, who spent a week at home fighting off a bad case of fatigue, returned to work Saturday — more evidence that the virus doesn’t always win.

“I’m walking, living proof of that,” he said.

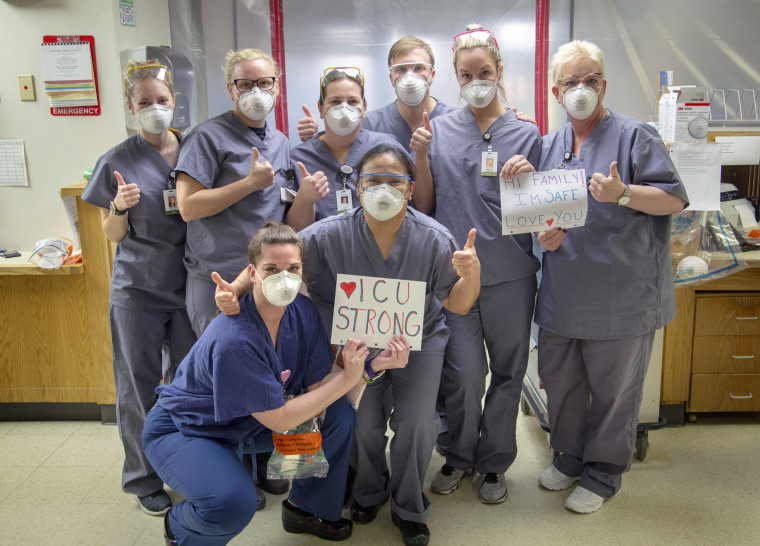

The ICU transformed to meet the surge of COVID-19 patients, said Jeff Rhode, a hospital photographer who’s been spending more and more time there to document the work of nurses and doctors. Among the most notable changes are the walls of plastic sheeting, he said. They separate patients, open and close by zipper and provide an extra layer of protection between hospital staff and patients.

“It started out as a couple of rooms,” Rhode recalled. “Then it was five rooms, then it was half the floor, and then I’d go up the next morning and the whole floor would be just plastic sheeting.”

“I can’t really describe the mood,” he added. “People are focused. They’re working. They’re tired. But, you know, they’re dedicated.”

In another building, Maron said the hospital is converting a ground floor meeting room and auditorium into more ICU space to house an estimated 40 beds. A local builder that specializes in modular design said it could be ready in four days, he said.

In the meantime, the hospital consolidated its COVID-19 patients on ventilators, moving them April 2 from the ICU to a new unit with 36 beds called “the shell,” Van Dyk said. The idea was to centralize the patients in a new structure — it was built in less than a week — to make it easier for her and other staff to tend to them, she said.

Each patient required eight movers and roughly 30 to 40 minutes per move.

“It was exhausting,” she said. “Everybody’s just exhausted.”

Still, there was a sliver of encouraging news: nobody died that day, Van Dyk said. And they even weaned a few patients from their ventilators, lowering their sedation so that they were more alert.

“They’re doing more breathing on their own,” she said. “And we’ll watch them like that for, say, 24 hours. If they look good, then maybe tomorrow we’ll be able to remove" the ventilators.

“We’re starting to see positives, which we need right now,” she added.