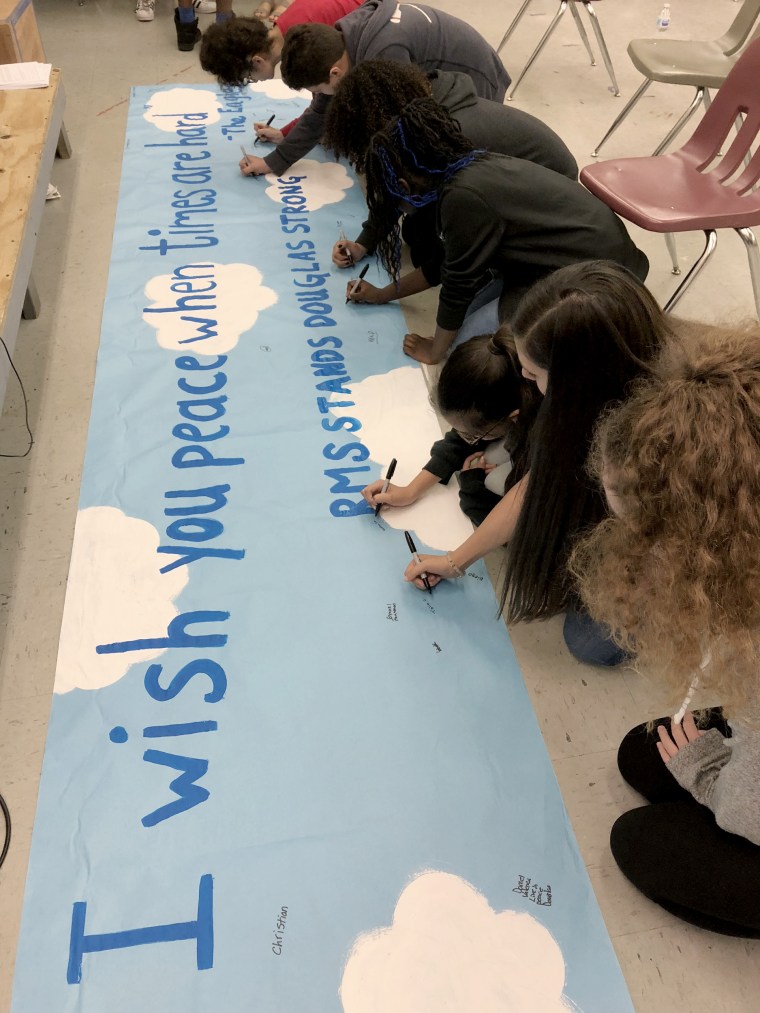

At Ramblewood Middle School in Coral Springs, Florida — less than a 20-minute drive from Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School where 17 people were shot to death on Wednesday — students have been asking: What if it happens here?

Only half the class came in on Thursday and Friday, according to Ramblewood drama teacher Meagan Nagy. The rest are too scared to come to school.

And those who have shown up are on edge.

"Every time there was a knock at my door, any time the bell rings, the intercom went off, the students jumped," Nagy said. "They were scared."

They also had questions:

"Why did the gunman do it?"

"How did it happen?"

"Where will we hide if a shooter comes to our school?"

Like Stoneman Douglas, Ramblewood is in the Broward County public school district. Many of its students go on to Stoneman Douglas, in neighboring Parkland, for high school, and many have older siblings or friends there.

Related: Parkland school shooting: Football coach Aaron Feis died shielding students

For the past two days, Nagy has used her class time to let students cry and grieve. She's shared with them the procedures that she and other teachers have rehearsed in the event of an emergency. She's even enlisted their help with making a place in her classroom where they could hide if there was a shooting.

"I spent a drama class with my kids cleaning out a closet, because I have 46 kids in my class," she said, "in the event that this happens again — and I have to hide 46 kids."

Nagy said she doesn't want to "pretend something didn't happen, because something happened, and something very bad happened." But she also said she's tried her best to make her 6th, 7th, and 8th graders feel safe as they process the deaths of students and teachers at the high school barely a dozen miles away.

"Three colleagues lost their lives two days ago by standing in front of bullets, by standing in front of kids," Nagy said. "I said to my kids, 'I would do the same thing for you, and I want you to know that it's OK to come to school because your teachers will keep you safe."

In schools across the United States, the deadliest school shooting since the 2012 massacre in Newtown, Connecticut, has led to difficult discussions between teachers and their students, whose sense of safety inside their classrooms has been shattered — again.

Related: Florida school shooting: These are the 17 victims

"Educators across the country get up each and every day to make the future for the students they work with better, and it seems like it should not need to be said, teaching and learning cannot occur where children and educators do not feel safe," said Mary Kusler, senior director at the National Education Association's Center for Advocacy. "Their number one job when they woke up and went to school on Thursday morning was to make sure that each of their students felt safe."

Educators must reassure children and "validate their feelings and help put them in perspective," Kusler said.

"We need to create time to listen and be available to talk with both students and their parents, and we need to recognize that kids will express that in different ways," she added. "Some of them will want to talk or draw or write, or find some other outlet. A lot of it needs to be developmentally appropriate: what you do at an elementary school and a high school are very different."

At Glenbard North High School, in the Chicago suburb of Carol Stream, Illinois, government and psychology teacher Erica Bray-Parker's students have been asking her about the Parkland shooting after watching horrifying videos taken by students inside Stoneman Douglas that have been posted on social media.

"I flip it and say 'stop watching this,' and 'what action can we take? Are there policy makers we can contact? Is there a not-for-profit organization? Voice your opinion,'" she said.

Bray-Parker has been a teacher for 24 years, so her students' confusion and horror after the Parkland shooting brought back memories of how her students responded to the 1999 Columbine, Colorado, shooting, when she was teaching at another Illinois high school.

But so many school shootings later, Bray-Parker said it's hard not to fear the worst happening at her own school.

"I drove into work thinking what if it happened, what exit door would I use, what would I do with the children I'm responsible for?" she said. "I usually think about my lesson plans. I just want to teach the electoral college."