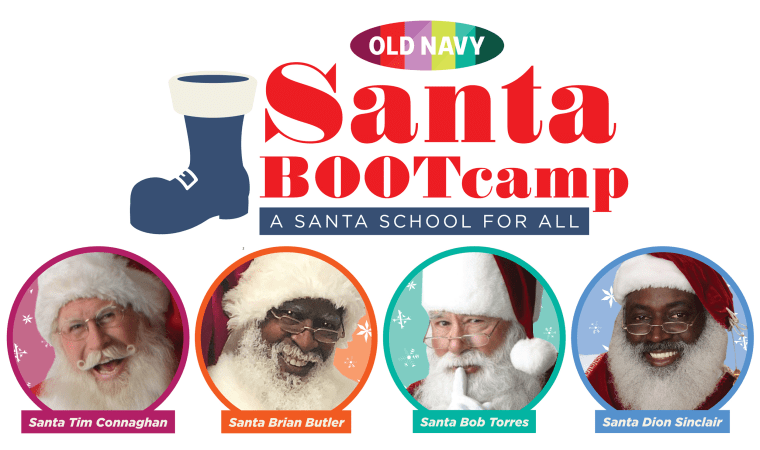

Old Navy is launching a virtual “Santa BOOT Camp” on Friday to train would-be Kris Kringles of color in the art of spreading holiday cheer and make the ranks of the people who play the iconic Christmas character a little less white. But as conservative pundits and politicians stoke white grievance and a national battle rages over the teaching of critical race theory, one of the original Black Santas has some advice for the newbies who intend to don the red suit this season: Disarm the bigots with Christmas cheer.

“I’m not about politics and I’m a faith-based Santa, so I know I am not the reason for the season and I’m happy to share that with anyone willing to listen,” Dion “Santa Dee” Sinclair, aka “The Real Black Santa,” told NBC News. “But if I’m not your kind of Santa, that’s OK. I will keep smiling and wishing the kids Merry Christmas and Happy Holidays.”

Besides, Sinclair said, “the kids don’t see color. All they see is Santa Claus.”

Other stores like Macy's and major retail outlets like the Mall of America in Minnesota have also tried to diversify their Santa ranks, delighting many shoppers while dismaying others.

“It is a concern,” another of America’s premier Santas, Tim “Santa Tim” Connaghan, said when asked about the anger over nonwhite Santas. “Change is hard for some people, and things are definitely changing.”

What’s not addressed specifically in the Old Navy tutorial is how a nonwhite Santa deals with bigotry, a company spokesperson said.

“Our Santa BOOTcamp is a lighthearted experience aimed at bringing out the inner holiday spirit in all of our attendees,” a company statement said. “We will provide guidance on some of the most common challenges of playing Santa, including how to handle outrageous gift requests and to temper potential disbelief in little ones."

That said, Old Navy said it “stands for inclusivity and has a zero tolerance police for workplace discrimination and harassment.”

"Our brand is deeply committed to ensuring all employees — inclusive of our in-store Santas — are treated with respect and dignity."

Sinclair, who is 57 and says he “became Santa Claus” some 20 years ago, is one of the Santa trainers taking part in Old Navy’s “Happy ALL-idays” campaign.

In the 30-minute virtual course, the Santa trainees will also learn some key phrases in both sign language and Spanish, and how to take that perfect holiday photo, he said.

“One of the most important things is to never make a promise you can’t keep,” Sinclair said. “If a child wants a certain present, you say ‘Let’s see what we can do.’ In my heart, I would give every kid the toy they want out of my bag. But the parents can’t always afford the present their child wants.”

The most promising Santa boot camp grads could find themselves deployed to Old Navy’s flagship stories in New York City, Chicago and San Francisco.

“There aren’t a lot of Santa’s out there who're like me,” said Sinclair. “It’s even harder to find an Asian Santa. Believe me, I’ve tried.”

Connaghan, who is the national Santa for the Marine Corps and Toys for Tots, agreed. He, too, is taking part in the Santa BOOT Camp.

“Businesses like Old Navy understand that more and more customers want their Santas to look like them,” said Connaghan, who also owns the Kringle Group, which is one of the largest Santa booking agencies. “But it’s just very hard to find an Asian or Hispanic or African American Santa, especially one with a full white and real beard. Many are, I guess you can say, follicly challenged.”

“I am lucky,” Sinclair, who sports a bushy white beard year-round, said. “But lots of Black men have trouble growing a beard like mine, and the theatrical white beards don’t fool the kids anymore. The kids are smart. They can tell when somebody is wearing a fake beard.”

Sinclair’s and Connaghan’s assertion about the scarcity of nonwhite Santas is backed up by some actual numbers.

In a nation where half the children under the age of 15 are nonwhite, less than 5 percent of the professional Santas working the malls and street corners and festive gatherings are Black or Asian or Hispanic, according to a Santa survey done in 2017 by The Tampa Bay Times.

But the idea of Santa being anything but an elderly white man with a big beard and rosy red cheeks has never sat well with some segments of U.S. society when Black Santas first started appearing after World War II.

In 2013, then-Fox News personality Megyn Kelly sparked a firestorm when she insisted on her show that both Santa and Jesus were white and anybody who believed otherwise needed to get over it.

Three years later, the Mall of America was hit with an online backlash when it hired Larry Jefferson as its first Black Santa, a process that required a nationwide search.

Sinclair, a father of four and grandfather of two based in Atlanta, said he came face-to-face with that ugliness early on in his Santa career when he found himself working the evening shift at a mall in a mostly white Atlanta neighborhood.

“A mom came who’d been in the mall earlier in the day and saw a white Santa and came back later in the day with her kids and, lo and behold, she found me,” Sinclair said. “'That’s not the Santa we’re looking for,' she told the manager. Her little daughter looked so disappointed. She just wanted to see the fat men in the red suit.”

Why isn’t there more diversity among Santa Clauses? Connaghan addressed that very question in an essay several years back.

Santa is based on the historical St. Nicholas, who is believed to have been a Greek bishop living in what’s now Turkey. But whenever he was portrayed in paintings during the Middle Ages and Renaissance he “mirrored the ethnicity of that community,” wrote Connaghan.

Good old American commerce help solidify the image in the American psyche that Santa was, as Connaghan put it, “a white male with a beard of white.”

As a result, many children were brought up with the idea that Santa is white.

But good old American commerce also recognized rising Black consumer power after World War II and began hiring Black Santas to entertain children at department stores during the Christmas season, historian E. James West wrote in The Washington Post last year.

Still, the resistance to a Black Santa “can be connected to the so-called War on Christmas which has become a conservative rallying cry over the past two decades,” West wrote.

Connaghan said many generations of America grew up with a fixed concept of what Santa was supposed to look like “and just accepted it.”

"That includes a lot of Black and Hispanic people who never thought of Santa as being anything other that white, like the Coca-Cola Santa," he said.

But as the country changes, so, too, will the country’s concept of Santa, Connaghan and Sinclair said.

“I think, in a couple of years, most people won’t be looking for Santas with white beards, and won’t be expecting a Santa that looks like Tim Allen,” Connaghan said, referring to the star of the 1994 movie “The Santa Clause,” who is also white. “Santa is constantly evolving.”