The noise in the hallway could have been anything: a locker door shutting, textbooks dropping on the floor. But when he heard a sudden sound outside his classroom a couple of weeks after the Florida school shooting, Dan Greenberg, a high school English teacher in Sylvania, Ohio, assumed the worst.

"The immediate response is thinking about the shooting, thinking about what happened in Parkland," he said, adding that before the Feb. 14 massacre, "that was never the first thought in my mind."

Now, Greenberg said, he's hyper-aware of the possibility of more school shootings.

"That's scary to have that as the default mindset," he said.

During the same week, over at Pine Ridge Elementary School in Aurora, Colorado, special education teacher Jennie Campbell was showing her third-graders an educational video in which Blackbeard, an infamous pirate, gets shot. She hadn't discussed the Parkland shooting with her students, youngsters with moderate to severe needs who she describes as "resilient but also very aware of what's going on."

"One of my students said, 'There's gunshots, just like at the school in Florida'" after seeing the pirate get shot, Campbell said. "I didn't even think about it at that moment. What do you do? What do you say to that?"

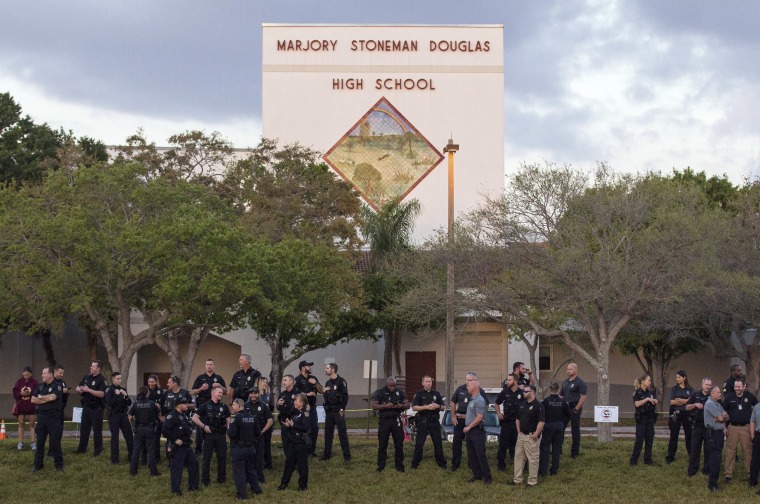

The shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland happened nearly a month ago, and hundreds of miles away from Sylvania and Aurora. But the attack, which left 17 people dead, has left an indelible uneasiness among teachers and students across the country — and a determination to bring a sense of safety back to the classroom.

"It's an everyday conversation, and it’s not just school safety. It’s 'what are we going to do about it?'" said Justin Fox-Bailey, a high school English teacher in Snohomish, Washington, for 20 years and the president of the Snohomish Education Association, the teachers union there.

"They don't want to see any more kids die at school. They don't want to see any more teachers or other educators die at school."

"I don't hear from teachers on any given day that they're worried for their safety," he said. "But they're worried generally, and they don't want to see any more kids die at school. They don't want to see any more teachers or other educators die at school."

On Wednesday, thousands of students across the U.S. plan to participate in a National School Walkout to protest gun violence, stepping out of class for 17 minutes in honor of each Parkland victim.

While some schools say they will discipline students for participating in the walkout, others, like Winter Hill Community Innovation School in Somerville, Massachusetts, are taking a different approach.

"We want to have a discussion with students about what this means to them and listen to their voices, because that's important," said Chad Mazza, principal of Winter Hill, which has about 400 students from pre-kindergarten through eighth grade. "The students appreciate that. They know we care about what they think."

While the national walkout is student-led, some educators say they want a chance to galvanize, too. At Chelsea High School in Chelsea, Alabama, principal Wayne Trucks expects some teachers to come to school wearing orange — symbolizing their support for gun control. The high school plans to host a forum in an auditorium on Wednesday where students and teachers can express themselves.

"We're going to give teachers an opportunity to participate, as long as they provide supervision for the students who don't want to participate," Wayne said.

Other teachers have set their sights on a walkout of their own. Campbell, the special education teacher in Colorado, said her local educators' group, the Cherry Creek Education Association, is considering a teachers' walkout on April 20 — the anniversary of the 1999 Columbine High School shooting.

Such a walkout, she said, would give educators a chance to voice their opposition to a proposal by President Donald Trump to train and arm some teachers. Last Friday, Florida Gov. Rick Scott signed new gun restrictions into state law, including a provision that allows teachers to arm themselves, and the White House on Sunday promised federal aid to train teachers to carry weapons.

"It blows my mind that rather than having a sit-down conversation about what we can do to change and help schools, let's just fix it by arming teachers," Campbell said. "I went to school to teach kids, to have them love learning and help them find what their passion is. I did not go to school to protect children in that sense."

Fifty-six percent of Americans disagree with Trump’s proposal to have some teachers carry concealed guns to increase school safety, according to an NBC News|SurveyMonkey poll.

Related: Poll: Majority of Americans disagree with Trump's proposal to arm teachers

But some educators have cheered the idea — including those at the Harrold independent school district in the tiny rural town of Harrold, in West Texas. The district is believed to have been the first in the nation to arm teachers when it began in October 2007.

According to Superintendent David Thweatt, it has quelled fears of "what if it happens here?"

"I can't imagine taking on the dual role of taking care of kids and making sure their needs are met educationally, socially and emotionally, and then at the same time, having a loaded weapon and having to defend students if the need came up."

"The parents are glad that their kids are protected. After every shooting, you get copycat situations, and we don't get those," said Thweatt, who created the program after five people were killed in a 2006 shooting at an Amish schoolhouse in Pennsylvania.

At Sidney City Schools in Sidney, Ohio, not only are more than 40 teachers armed, but their classrooms have bulletproof vests stashed in them, said Superintendent John Scheu. Teachers "go through an immense amount of training to be even considered" to be armed, he said.

"When President Trump said he's for arming teachers, I think this is taken out of context, because I don't think he means arming every teacher with a handgun," Scheu said. "I think he means those who are physically, emotionally and psychologically capable."

Greenberg, the Ohio English teacher, want lawmakers to think of other solutions — such as more school counseling services and less access to firearms.

"I can't imagine being armed myself," Greenberg said. "I can't imagine taking on the dual role of taking care of kids and making sure their needs are met educationally, socially and emotionally, and then at the same time, having a loaded weapon and having to defend students if the need came up."

CORRECTION (March 12, 2018, 4:36 p.m. ET): A previous version of this story misidentified the subject matter of an educational video. It was about a pirate, not a bear.