DENVER — When Covid-19 hit the U.S. in March, revenue at Alyssa Manny’s yoga studio fell 60 percent to 70 percent. And it wasn’t just her. Nearly every business on Tennyson Street, in a gentrifying neighborhood about 15 minutes from downtown Denver, was hit hard by the pandemic.

First to go was Biju’s Little Curry Shop, a popular dining spot featuring dishes that Biju Thomas grew up with in south India, like samosa chaat, dosas and rotis. He moved to the U.S. in 1980 and settled in north Denver. February had been his best month since he opened the restaurant in 2016. But by March, he was done.

“We lost $80,000 in bookings that first week,” Thomas said recently. “We had weddings and events booked into March, April, May. We did about $400,000 in catering and events over the course of a year. Fifteen hundred meals a day out of the kitchen. There’s no coming back from that.”

Thomas’ experience is echoed by small-business owners across the country who have fallen on hard times since the start of the pandemic, which has killed over 260,000 people in the U.S. and strangled the economy. At least 100,000 small businesses nationwide have closed permanently, according to a Yelp analysis released in September. Many others are barely hanging on.

Small businesses make up 44 percent of U.S. economic activity, according to a 2019 report from the Small Business Administration. Restaurants, which before the pandemic employed 15 million people, have been especially hard hit. The wreckage is evident in empty storefronts, takeout-only signs and GoFundMe pitches to help merchants stay afloat.

“No one was prepared for the reality of shutting down an entire economy,” said Manny, owner of Ohana Yoga + Barre and vice president of the local merchants’ association. “Business owners had to decide, do you want to take on debt and play the long game or get out?” Manny chose the former, taking on $200,000 in debt and turning her popular studio into a membership-only operation.

In the early 20th century, streetcars ran along 38th and 44th avenues, and riders hopped off at Tennyson to shop and go to the movies. Over the decades, the bowling alley became a grocery store; the movie theater, a music store; and the post office, a furniture store. Other small businesses moved in, like a barber shop, a print shop and a corner bar.

The Tennyson Street commercial corridor, with its eight blocks of restaurants, breweries, an independent bookstore and The Oriental Theater, a venue for live music performances, is the beating heart of the community. Today, Tennyson is rapidly gentrifying, and in a nod to the transformation, the high-end athletic-wear purveyor Lululemon recently opened a seasonal pop-up, Corepower Yoga moved in and a boutique hotel is coming in January.

But some residents are critical of the changes, which include apartment buildings without ground-floor retail to promote foot traffic, saying the trendiness is out of character with a neighborhood where century-old bungalows sit beside contemporary apartments.

Along Tennyson, a vibrant painting of a buffalo hangs in an art gallery window and the scent of citrus candles greets pedestrians outside a nearby shop. The familiar notes of “It’s Beginning to Look a Lot Like Christmas” rise out of an antiques store, and passersby know what the restaurants are serving just by breathing — bacon, toast, red sauce, pepperoni.

Over the spring and summer, restaurants that survived the initial shell shock of Covid-19 pivoted to takeout and outdoor dining. Picnic tables moved to parking lots and vacant plots of land, and the street had a party-like vibe. Three houses that had been slated for demolition became pop-up spaces for an interactive art experience sponsored by a marijuana brand. The Wana Art House featured a magic circus, the Beach House projected immersive beach scenes and The Club House was a place for pop-up art and boutique sales.

But with the turn of seasons, businesses shut down again. Fencing surrounds the former art houses, and Local 46, a popular watering hole with a tree-covered patio, closed for good on Halloween.

Hops and Pie, a pizzeria owned by Drew Watson and his wife, Leah Watson, had a busy summer, but a short video they released in November informed customers they were moving to takeout and delivery indefinitely. The heated outdoor tent they had just erected would sit empty as the state announced that one in 41 Coloradans were testing positive for Covid-19. No indoor dining would be allowed, not even in a tent.

“This has surely been the worst year we’ve ever had by a landslide,” said Watson, who has owned the eatery for 10 years.

On Nov. 16, word came that the Alchemy 365 fitness studio was shutting down after opening in January, occupying the entire first floor of a residential building. During the pandemic, membership declined by over 60 percent, said co-owner Tyler Quinn. The business received federal Paycheck Protection Program loans, enabling most of its staff to stay on for a while, and the landlords adjusted rent payments. But it still wasn’t enough.

“It’s terribly disappointing,” Quinn said. “This was designated as a really aggressive growth year for us. We’re going to be delayed if not completely derailed on our long-term vision.”

Two of his seven locations, one on Tennyson Street and one in Minneapolis, were forced to close during the pandemic. Quinn and his team were discouraged by the lack of leadership from all levels of government to help navigate the crisis.

“It doesn’t feel like there’s anybody out there thinking, ‘How do we support these small businesses?’” he said.

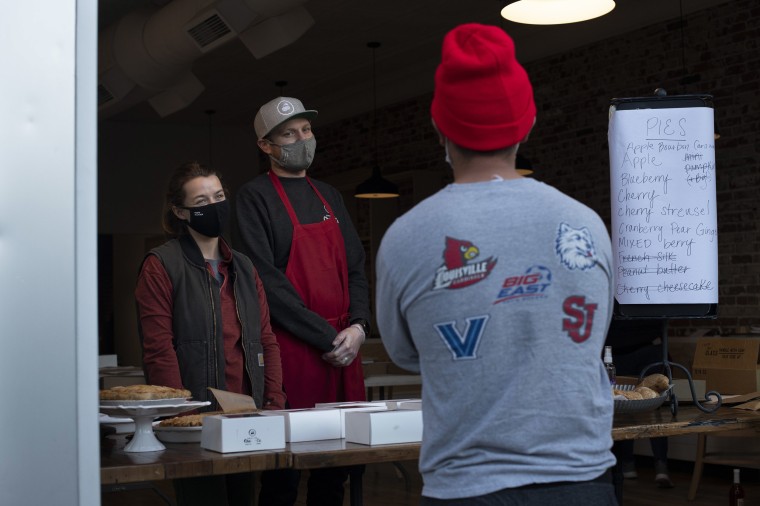

Despite Covid-19, Elias Lehnert decided to move forward with the newest Colorado Cherry Company pie shop after his landlord sweetened the deal. His family started the business in 1929, and his parents have three stores in northern Colorado.

“Pie is comforting. It’s like a hug,” said Lehnert, who represents the fourth generation of his family in the business. “People just need a hug right now in a lot of different ways. “

Lehnert, who began setting up his pie store in August, said the building’s owner, Asana Partners, offered him the space rent free until he opened in November, and he’s paying up to 15 percent less than a previous prospective tenant was offered.

He is starting cautiously with pop-ups for the holidays, having customers order a pie and pick it up at the takeout window.

“They want to see us succeed,” Lehnert said of the landlords. “I feel a lot better that we don’t have the pressure to be fully open today. … If I had to be fully open, I’d be very scared.”

The handful of developers who have staked their claim on Tennyson Street also face uncertainty. Lenny Taub, who owns First Stone Development, is working on his second project on Tennyson Street. He sold out a 42-unit apartment building this year, but the pandemic has changed his approach for his next development after he had trouble moving smaller units.

“What I learned during the middle of the pandemic is people were looking for elbow room and they were willing to spend money for larger spaces,” Taub said.

He hopes to break ground on his next apartment building by spring 2022, with fewer studios and more two-bedroom units. Taub expects the gentrification of Tennyson to continue, pandemic or no pandemic.

“It’s the walkability. It’s really a nice place to walk,” he said. “I see the attraction. I see why young families are moving in there. It’s a great place to bring children up.”

Still, Alyssa Manny worries that Covid-19 will permanently alter the mom-and-pop nature of Tennyson Street because only national companies will be able to afford leases as small businesses close and landlords stop providing pandemic rent relief.

“It’s our small businesses on our streets that are constantly giving back to our communities,” Manny said. “We’re the ones sponsoring baseball teams and giving back to the homeless. We want to see this whole area continue to thrive.”