A trailblazing Black priest who was a civil rights hero to many African American Catholics was accused Tuesday of being an alleged sexual abuser of a young boy in an $800,000 settlement reached with the Archdiocese of Chicago, according to a lawyer for the boy.

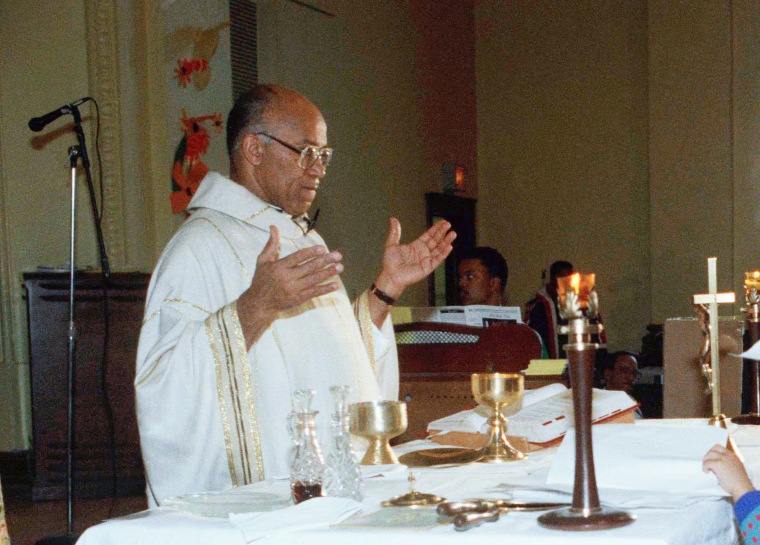

The Rev. George Clements was the pastor of the Holy Angels Church in Chicago when he allegedly began preying on the then 7-year-old boy in 1974, according to the accuser’s attorney, Mitchell Garabedian.

The alleged abuse, which happened at least 20 times until 1979 when the young man turned 12, took place in the church rectory, in Clements’ car, and while on a camping trip, the lawyer said.

“It was the worst you could imagine,” Garabedian said of the alleged abuse during a news conference in Chicago. “When my client reported the abuse to his mother, [he says] his mother locked him in the closet and said, ‘Don’t ever talk about Father Clements like that again.’”

Garabedian called on Cardinal Blase Cupich, head of the archdiocese, to place Clements on the archdiocese’s public list of “credibly accused priests.”

“The hiding has to stop,” said Garabedian, a Boston lawyer whose efforts on behalf of predator priest victims were dramatized in the Oscar-winning 2015 movie “Spotlight.” “The secrecy has to stop.”

The $800,000 in settlement money, which was agreed upon through private mediation, will also be shared by the sex-abuse victims of four other Chicago-based Catholic clergymen, Garabedian said.

The Archdiocese of Chicago declined to comment on the settlement or on Clements, who was 87 when he died in 2019.

“We don’t comment on lawsuits, claims, or settlements,” a spokesperson for the archdiocese replied via email.

Legal settlements, including this one, often do not include an admission of wrongdoing.

Clements’ accuser, who is now 54 and lives in the Chicago area, was not at the news conference.

Garabedian insisted his client was “not the same man” who accused Clements of sexual abuse back in August 2019.

At the time, Cupich asked Clements “to step aside from ministry” pending the outcome of an investigation and the accused priest told The Chicago Sun-Times the allegation was “totally unfounded.”

The state Department of Youth and Family Services said they had found no evidence to back up the claim and Clements’ name is not on the list compiled by the Archdiocese of Chicago of priests who have been credibly accused of sexually abusing a minor.

“For the sake of transparency and healing Cardinal Cupich has a moral responsibility to publicly list Fr. George H. Clements on the publicly credibly accused sexual abuser list of the Archdiocese of Chicago,” Garabedian said in an email to NBC News.

A Chicago native, Clements was only the second Black priest to be ordained by his hometown archdiocese. He became one of the best-known Roman Catholic clerics when he marched for social justice with Martin Luther King Jr. in Alabama and Mississippi as well as Chicago.

Clements also became the first American priest to adopt a child and wound-up raising four sons. His foray into fatherhood was depicted in “The Father Clements Story,” an NBC television movie made in 1987 that starred Lou Gossett Jr. as the pastor.

About a decade later — but well before the Catholic Church was engulfed by the priest sex abuse scandal — Clements said in a 1995 interview that he had reservations about the priesthood.

At that point Clements was getting heat from his superiors for staging sit-ins at stores that sold drug paraphernalia near his church, protests that sometimes resulted in his being arrested.

“Had today’s climate been around in the ‘80s, I would never have adopted,” he said. “As a matter of fact, I wouldn’t have become a priest! I’m serious about this. Had I known back in 1957 that I was giving my vow of obedience not just to the cardinal archbishop of Chicago and his successors, but I was giving (it) to a review board! A group of people I know nothing about! They could be racists for all I know.”