In September 2018, an ambulance rushed Bonnie Austin to a nearby Columbus, Ohio, hospital after she complained to her husband of chest pains and labored breathing.

A night shift doctor in the intensive care unit named William Husel was in charge: He ordered 600 micrograms of fentanyl, a powerful opioid used to blunt pain, and a large dose of a sedative known as Versed, administered through an IV, according to her medical records.

About a half-hour later, Bonnie Austin, 64, would be pronounced dead, the records show.

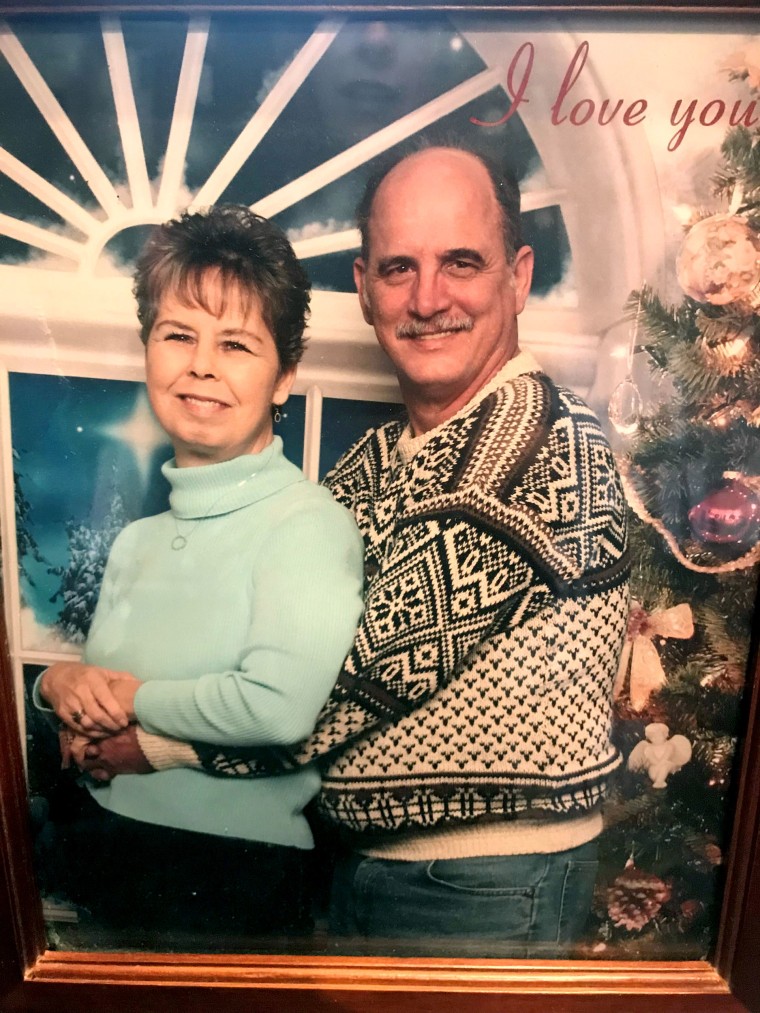

David Austin said it was Husel who first delivered the gut-wrenching news to him that his wife of 36 years was brain-dead. But he insisted he would have wanted the doctor to do everything within his power to try and keep her alive.

"Of course I wanted my wife to survive," David Austin told NBC News in 2019.

The amount of painkiller Husel allegedly ordered at the moment he did will become the focus of a long-awaited trial in which the doctor, whose medical license was suspended in January 2019, faces murder charges in the deaths of 14 intensive care unit patients. Jury selection is set to begin Monday in the trial.

The case became a stunning example of alleged medical malpractice with prosecutors in Franklin County initially charging Husel in the deaths of 25 patients. They said he ordered excessive doses of opioids to dozens of near-death patients between 2015 and 2018, when he was employed with the Mount Carmel Health System, one of the largest in central Ohio.

A new prosecutor in Franklin County, G. Gary Tyack, winnowed the number of counts down to 14, centering the trial on patients who were allegedly given higher doses of fentanyl — as much as 1,000 micrograms. Medical experts have said a typical dose for nonsurgical situations might be around 50 to 100 micrograms.

The amount of fentanyl allegedly ordered is only one facet of Husel's trial, which had been delayed during the pandemic and could last up to two months. Themes of medical treatment and ethics, and end-of-life comfort care using opioids are expected to come into play in one of the biggest cases of its kind against a health care professional in the United States.

In addition, complex medical testimony, emotional stories from the families of the deceased and the notoriety brought by Husel's defense team will make for an intriguing set of proceedings, observers say. The team includes high-profile lawyer Jose Baez, who once counted NFL player Aaron Hernandez, Florida mother Casey Anthony and Hollywood mogul Harvey Weinstein as his clients.

"It puts a lot of drama on the trial," said former prosecutor Ric Simmons, who teaches criminal law at Ohio State University. "The defense can say that you think you know this story, but you don't know the whole version yet, and you shouldn't put a judgment on it until you do."

'Good faith' defense

Husel, 46, has not spoken publicly or given media interviews since the allegations of misconduct first arose in a series of lawsuits filed by families in early 2019. When he appeared before the state medical board that same year as it weighed whether to suspend his license, members said he asserted his "Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination to virtually all questions."

Husel, who pleaded not guilty, has remained free on a $1 million bond.

Legal experts say his trial will offer a more nuanced view of the doctor, who began his career with a residency in critical care at the prestigious Cleveland Clinic, as the prosecutors and the defense outline their cases.

While Husel faces murder counts, prosecutors could offer evidence to jurors of another option: a lesser offense of reckless homicide for each count. While a murder conviction carries a sentence of life in prison with no chance of parole for 15 years, reckless homicide, which in some states is a type of involuntary manslaughter, has a penalty of up to five years in prison.

For each charge of murder, prosecutors must prove that Husel purposefully caused the death of the patients under his care. That will be trickier in this case, Simmons said, because the patients who died were generally already dying or close to it.

Therefore, he added, prosecutors will also need to show that each patient died because of how much fentanyl Husel authorized, and that perhaps they could have lived longer or their lives could have even been saved.

If prosecutors steer toward a reckless homicide argument for a particular count, then jurors would have to decide whether the doctor knowingly engaged in behavior that could result in a death, and not that it was his intent to kill.

In Husel's case, prosecutors could say "the first or second time could be accidental, but by the 14th time, he must have known or was at least aware of the risk someone was going to die," Simmons said.

The defense has argued to the court that Husel should be immune from prosecution because Ohio law declares that physicians who say they were acting in "good faith" shouldn't be held liable even when a "medical procedure, treatment, intervention, or other measure may appear to hasten or increase the risk" of death.

But Franklin County Judge Michael Holbrook said in a response this month that such a claim will be a central question for jurors to decide: Was Husel acting in good faith?

His lawyers have contended that the answer is yes, and the doctor was trying to provide comfort to people who were dying and in excruciating pain as they were being taken off ventilators.

"Dr. Husel practiced medicine with compassion and care," Baez told reporters in December. "That was his intent. And under the law — Ohio law — is that even if that killed them, so long as his intention was medically-based, then it's not murder."

A request for further comment to Baez's law firm was not returned, and the Franklin County Prosecutor's Office declined to comment ahead of the trial.

Simmons said Husel's lawyers will be careful not to suggest that the ordering of large doses of fentanyl for comfort care was meant to quicken patients' deaths.

"We don't allow euthanasia in Ohio, so that is not a possible defense," he added.

Hearing from Husel

Many of the patients whose deaths are part of this case were in the ICU already dying or near death and older. A few were as young as their late 30s, but many were in their 70s and 80s.

Simmons said he would expect Husel to take the stand since it will be important for the jury to hear directly from him as to his thinking.

Also up for discussion will be if there was any apparent pushback from other hospital staff, including the nurses, over the amount of fentanyl allegedly ordered.

Attorneys for some of the victims' families have previously said that Husel may have been persuasive enough to get his medication orders filled, and colleagues working late nights beside him may not have felt they could overrule his commands.

At least three dozen co-workers, including ICU nurses, came to Husel's defense in a letter to Mount Carmel after he was fired. One former ICU nurse previously told NBC News that "it's ludicrous to think you're going to convince 38 health care workers to collude to end anyone's life prematurely."

The trial hasn't been the only legal battle hanging over Husel.

About 35 families filed wrongful-death lawsuits against him, the hospital and other staff, with several of the families settling for a total of about $13.5 million. Husel's wife, Mariah Baird, who was a nurse at Mount Carmel, was also named in at least one of the suits.

David Shroyer, a Columbus lawyer who represents families of two of the deceased who will be part of the criminal trial, including Bonnie Austin's family, said 10 lawsuits are still outstanding.

While the allegations center on Husel, Shroyer contends there was a larger oversight by the hospital and that a system for obtaining fentanyl and accounting for every vial of a drug was either missed or willfully ignored.

"These things were falling in a dark hole without any kind of review," he said.

In the wake of the allegations, the Mount Carmel CEO stepped down saying the hospital made "meaningful changes throughout the system," and it fired almost two dozen employees, including nurses, physicians and members of the pharmacy management team. The hospital declined to comment ahead of Husel's trial.

No matter the outcome of the criminal case, Shroyer said, a larger reckoning is needed to ensure that what happened to the Austins doesn't happen to any other family.

"It’s a whole system that failed," he said.