Seeking to ramp up the nation’s capacity to administer a possible COVID-19 vaccine, the Trump administration has signed a $138 million deal with the makers of an innovative syringe designed to be used in developing countries.

The goal of the public-private initiative, called Project Jumpstart, is to facilitate the production of 100 million prefilled syringes by the end of 2020 and more than 500 million in 2021 in the event a vaccine becomes available, officials announced Tuesday.

The Health and Human Services Department and the Defense Department are partnering with ApiJect Systems America, which manufactures inexpensive prefilled syringes made of plastic.

The project will "help significantly decrease the United States’ dependence on offshore supply chains and its reliance on older technologies with much longer production lead times," said Defense Department spokesman Lt. Col. Mike Andrews.

Vaccines are typically delivered to doctors and hospitals in small in glass vials, which are time-consuming to make and require the use of a syringe to draw out the vaccine. But ApiJect figured out a solution to a problem that has long stymied researchers: how to make an easy-to-produce prefilled plastic syringe.

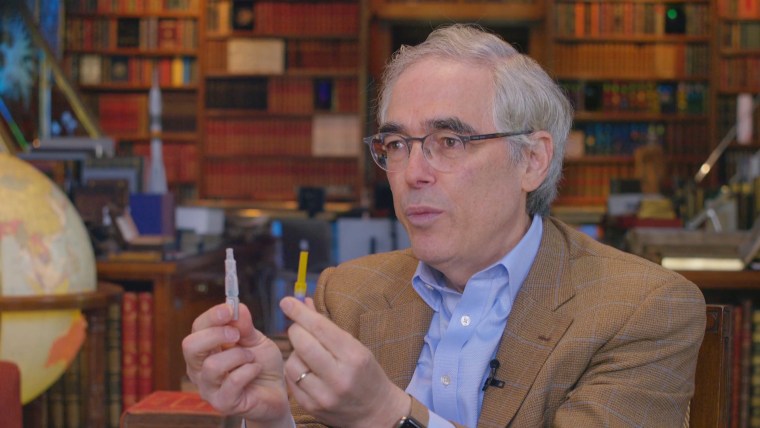

“Nobody has ever used an injectable prefilled syringe made of plastic in the tens of millions or even in the millions, because nobody had ever figured out how to attach a needle to a plastic filled container with a drug,” ApiJect CEO Jay Walker said in an exclusive interview with NBC News. “The technology to attach the two is the key to the uniqueness of what HHS saw we had solved.”

The device consists of an easy-to-attach needle and a plastic single-use container similar to ones used for eyedrops. The plastic syringes are made through a “Blow-Fill-Seal” manufacturing process, used in high-volume production for pharmaceutical grade products.

According to Walker, ApiJect’s prefilled plastic syringe will cost less than a dollar to produce, which is significantly cheaper than the cost of other prefilled syringes as well as glass vials.

The devices will be manufactured in the U.S. and planning is underway to retrofit facilities that already produce eyedrops and other similar items. ApiJect is also raising money to build new plants to help dramatically increase production of the syringes.

The deal comes two months after HHS announced that it selected ApiJect for an award valued up to $456 million for research and development of its syringes.

The new deal "will dramatically expand U.S. production capability for domestically manufactured, medical-grade injection devices starting by October 2020," Andrews said.

For more than a decade, experts in emergency preparedness and national security have warned about an inability to ramp up production of syringes in the event of a pandemic in the U.S.

Yet the U.S. still does not have the supplies or capacity to administer a vaccine anywhere close to the level that would be necessary for the coronavirus. A vaccine is not expected to be available until next year at the earliest, but experts inside and outside the federal government have expressed increasing concerns about the availability of syringes.

The manufacturing of glass vials to hold vaccines largely takes place overseas where costs are lower and environmental regulations are less stringent. It could take more than six months to produce just a few million of them, according to Walker.

“They're very specialized and very specific,” added Walker. “If you need tens of millions or hundreds of millions, they could take way longer to make. So that's a big problem.”

Public health experts estimate that a COVID-19 vaccine will require two doses to ensure immunity, requiring about 650 million just for the U.S. population alone.

“That's not just an order of magnitude or two” from current capabilities,” Walker said. “That's a whole new world of difference.”

In addition to the production of glass vials, the process of putting a vaccine into a container - known as ‘fill and finish’ - is also complicated. Existing facilities are already running at full capacity and built specifically for a given drug, officials say, and therefore cannot be easily switched over to package a new vaccine.

An HHS whistleblower, Dr. Rick Bright, sounded the alarm in March that the U.S. lacks enough vaccine-delivery capacity. Bright wrote in a whistleblower complaint filed May 5 that he raised the issue with his superiors at HHS earlier this year, telling them the nation’s stockpile “contains approximately 15 million needles and syringes, a mere 2 percent of the required amount.”

In a March 12 email to colleagues bolstering his complaint, Bright wrote: “It could take two plus years to make enough to satisfy the U.S. vaccine needs for a pandemic.”

The federal government first approached ApiJect in early 2019 to discuss the application of the new technology - originally intended for use in developing countries - to prepare for a potential flu pandemic. Following the outbreak of COVID-19 in China, a plan was developed to immediately increase surge capacity in the U.S. in anticipation of a vaccine or therapeutic treatment.

Two top officials with HHS’s Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response, Bob Kadlec and Joe Hamel, helped to spearhead the effort and worked to fast-track the process across agencies.

“They're thinking about every possible kind of pandemic and every possible kind of threat," Walker said. "They were stuck in a place where they said, ‘Look, we don't have a way to solve this problem.’”

The use of pharmaceutical-grade plastic as opposed to glass cuts down on the cost significantly, Walker said, and the containers are adapted from already existing packaging used for consumer eyedrops. Apart from attaching the needle, the syringes require no additional parts and are easy to maintain and dispose of safely, Walker said.

“Our product is simple for a really good reason: It's a global health product,” he added. “Our product is designed to be used by a midwife in a village in rural Africa to save a mother's life.”

The $138 million put up by the government represents only a fraction of the expected total cost of the initiative. Walker’s company is in the process of raising a billion dollars in private funding to complete the goal of producing more than 500 million syringes next year.

Though the government response to COVID-19 to date has been plagued by problems and delays, Walker says he is confident that they will be able to deliver millions of doses as soon as a safe vaccine is developed.

“We are going to do it,” Walker said. “It's not just feasible and possible. We are underway.”