Tennessee has been waiting more than three decades to kill Donnie Edward Johnson, Stephen Michael West, Charles Walton Wright and Leroy Hall.

This year, all four may die.

They are next in line in a jump-started execution schedule that has suddenly put Tennessee among states with the most active death chambers. After going nine years without putting anyone to death, Tennessee executed three people last year, second only to Texas. In addition to the four this year, it has scheduled two more in 2020.

This relative surge is unusual in America, where new death sentences and executions have dropped to historic lows and public opinion is turning against capital punishment. There were 42 death sentences and 25 executions nationwide last year.

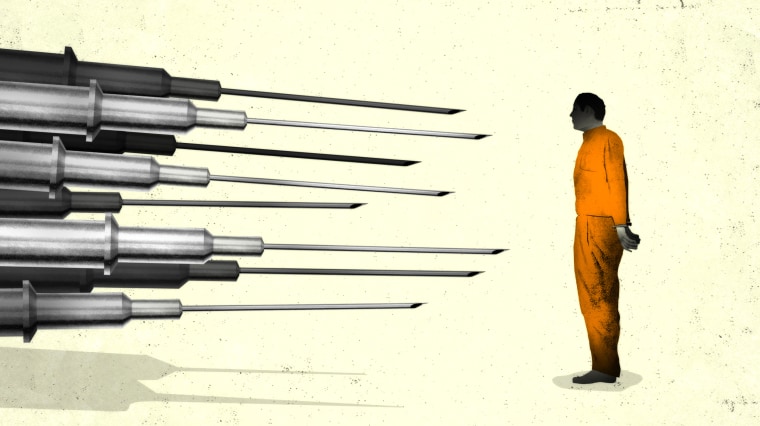

Much of the decline has to do with questions over the use of lethal injection drugs, the primary execution method in the 30 states that still allow the death penalty. Opponents say it is inhumane, and drug companies have resisted states’ attempts to use their products — often obtained secretly — to end someone’s life. The developments have made it increasingly difficult for states to carry out death sentences, with only the most persistent finding ways to continue.

“The death penalty seems to be retreating from most of the country, but there are pockets in which it is disproportionally used,” said Robert Dunham, executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center, a nonprofit that studies the use of capital punishment.

That includes Tennessee, where objections to the state’s lethal injection protocols — first involving a single drug, then, after it became too hard to find, a different three-drug mix — halted executions from 2009 to 2018. The hiatus ended when the state Supreme Court swept those objections aside last year.

The first of the new wave of Tennessee executions was on Aug. 9, when Billy Ray Irick was put to death for the 1985 rape and murder of a 7-year-old girl. On the eve of his death, his appeals reached the U.S. Supreme Court, which declined to intervene. Justice Sonia Sotomayor, in a dissenting opinion, called the process a “rush to execute.”

In the end, Irick was killed with a three-drug combination that was later described as torturous by a doctor hired by inmates’ lawyers — and prompted the next two men on the execution list, Edmund Zagorski and David Miller, to instead choose to die in an electric chair, a method all but abandoned for its barbarity.

“The significance of prisoners choosing a method known to be painful over something that is less known and could take longer, is extraordinarily significant and brutal,” said Megan McCracken, a lawyer at the University of California, Berkeley School of Law’s Death Penalty Clinic. “Prisoners are choosing it over the mix when they hear or see reports of other prisoners remaining alive, breathing, struggling, exhibiting signs of pain and suffering.”

Much of the opposition to the three-drug cocktail is based on the use of midazolam, a sedative that is supposed to render inmates unconscious before the administration of the remaining drugs — one that paralyzes them and one that stops their heart. Legal challenges have included evidence that the midazolam doesn’t prevent the inmate from feeling pain, and could cause pulmonary edema, which can make people feel as if they’re drowning in their own fluids.

“The basic argument is that this is torture and because this is torture it should be considered unconstitutional,” said Brad McLean, who represents a man scheduled for execution in Tennessee in April 2020.

Two men with looming execution dates in Tennessee, Stephen Michael West (Aug. 15, 2019) and Nicholas Todd Sutton (Feb. 20, 2020) have filed a lawsuit seeking to be killed by firing squad, an unlikely possibility that could only happen if the state can no longer obtain lethal injection drugs and the electric chair is found to be unconstitutional. Only Mississippi, Oklahoma and Utah currently allow death by firing squads, although Utah is the only one to use it ─ three times ─ since 1977.

Tennessee death row inmates have challenged the state’s three-drug protocol in a series of lawsuits and court filings. The case reached the state Supreme Court, which in an October hearing focused on requirements set by a 2005 U.S. Supreme Court ruling that inmates prove that a less painful method is available. The Tennessee inmates argued that the state could use a single drug, pentobarbital, which it had accepted in the past. But the state’s lawyers said it could no longer obtain the drug. The state Supreme Court ruled against the inmates, saying there was no clear alternative to the three drugs Tennessee is currently using.

The move to execute more people in Tennessee stands in contrast to Ohio, where a federal judge found in January that a similar three-drug method caused “severe pain and needless suffering.” In response, Gov. Mike DeWine, a Republican, postponed an inmate’s execution and ordered the state to seek alternative drugs.

Later this year, another important ruling on lethal injections is expected, this time from the U.S. Supreme Court. It is considering a Missouri inmate’s claim that lethal injection would lead to a “gruesome” death because he suffers from a rare condition that would make it difficult for executioners to find a vein to administer the drugs, and would cause him to choke on his own blood. Lawyers say the ruling could affect other cases involving elderly or infirm death-row inmates.

Tennessee’s execution schedule represents the culmination of cases that began decades ago, when the use of capital punishment was at its height in America. While the state has 58 people on death row, only two of them were sentenced since 2013.

“It is ironic that in a time where the number of executions has decreased significantly, Tennessee has experienced a sudden rush to execute so many men in such a short period of time,” said Kelley Henry, a federal public defender who represents three of the men on Tennessee’s execution list.

Tennessee’s execution schedule:

May 16, 2019: Donnie Edward Johnson, 68, sentenced to death for murder in 1984

Aug. 15, 2019: Stephen Michael West, 66, sentenced to death for murder in 1987

Oct. 10, 2019: Charles Walton Wright, 63, sentenced to death for murder in 1984

Dec. 5, 2019: Leroy Hall, 52, sentenced to death for murder in 1991

Feb. 20, 2020: Nicholas Todd Sutton, 57, sentenced to death for murder in 1986

April 9, 2020: Abu Ali Abdur’Rahman, 68, sentenced to death for murder in 1987