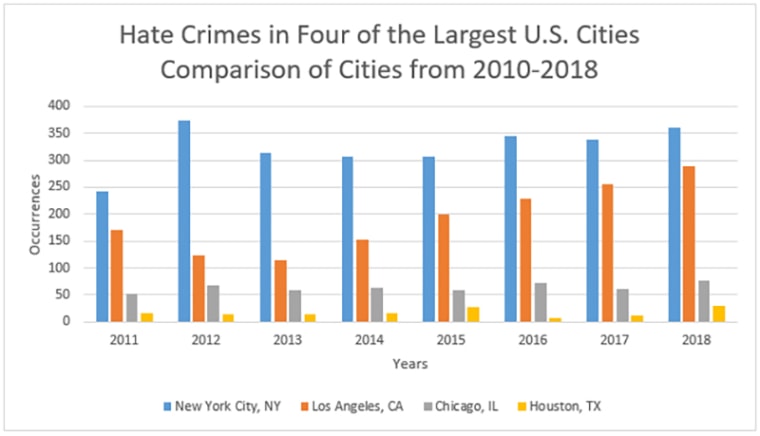

Hate crimes in major U.S. cities spiked around the time of the 2018 midterms, suggesting that extremist political rhetoric may be carrying over into actions.

The fall of 2018 had sharp increases in hate crimes in cities such as New York, Los Angeles and Philadelphia, said Brian Levin, director of California State-San Bernardino's Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism.

"In 2018, we saw spikes around election time in various U.S. cities, including the largest three," Levin told NBC News.

Though the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism has yet to finish its annual report, one reason why these diverse cities may be seeing more severe incidents of hate is that "hate-mongers" feel emboldened, Levin said.

In Los Angeles, for example, hate crimes fell in the first half of 2018 by 6.8 percent. But because they shot up in the latter half of the year, hate crimes were up overall by 12.5 percent compared to the previous year, according to Los Angeles Police Department numbers.

In the months around the 2018 midterms, October to December, hate crimes in the city rose more than 31 percent compared to the same period a year before. African-American, LGBTQ, Jewish and Latino communities appeared to be the most frequent targets.

"In looking at this correlation, we believe that around highly charged emotional events, like a terrorist attack or an election, the bully pulpit can make a difference," Levin told NBC News.

President Donald Trump held dozens of televised rallies during the 2018 midterm campaign, where he endorsed candidates, attacked Democrats and the press, and focused heavily on immigration, including a caravan of Central American migrants making their way through Mexico.

"As we speak, Democrats are openly encouraging millions of illegal aliens to break our laws, violate our borders and overrun our country," Trump said at a rally in Fort Wayne, Indiana, just before Election Day.

Hate crimes tend to spike after emotionally charged events, such as the 2018 midterms, then to stay at that level for some time before dropping off, according to Levin.

Before Trump launched his presidential campaign in 2015, hate crimes against Latinos were declining dramatically, Levin said. Then two weeks after the election in November 2016, anti-Latino hate crimes had the highest percentage increase of any groups, Levin said.

"Our center contends that the most common threat, the most prominent extremist threat right now, is undeniably far right and white nationalists," Levin said.

Almost every extremist suspect in murders in 2018 had far-right ties, according to a report published in January by the Anti-Defamation League.

To fight this trend, the ADL says public officials need to actively speak out against bigotry: "While we must continue to address that threat, the time has come to recognize that far-right extremism is an ongoing, pervasive and consistent threat to innocent lives in America."