SANTA FE, Texas — Alex Carvey hugged her friends, shed tears over white crosses bearing her classmates’ names and stood in silence for a moment. Then she reflected on the cause of the violence that hit her hometown.

“I don’t think guns are the problem — I think people are the problem,” Carvey, 16, a student at Santa Fe High School, said. “Even if we did more gun laws, people who are sick enough to do something like this are still going to figure out a way to do it. So it doesn’t matter.”

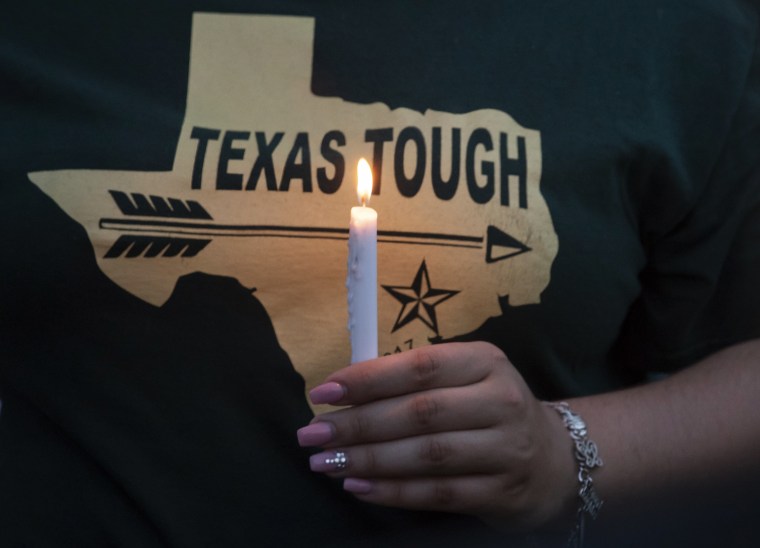

Many of Carvey’s classmates — along with their parents — agree with her. In contrast to the immediate aftermath of the Feb. 14 massacre in Parkland, Florida, when student survivors kicked off a national call for tougher gun control laws on social media and in street protests, there are few calls for new gun laws in Santa Fe.

Residents here still largely associate guns with hunting and family tradition, not mass shootings. In March, when students across the country walked out of schools to protest gun violence, just a handful of Santa Fe High School students participated.

“No matter how many laws there are, you can always break them,” said Nora Tulo, 15, a student at the high school.

Dimitrios Pagourtzis, the student charged in the Santa Fe shooting, was too young to buy a gun, Tulo pointed out, yet he was still able to use weapons belonging to his father. “He still brought a gun to school and he still killed 10 of our classmates,” Tulo said.

The stark differences in the responses to the mass shootings just three months apart serve as a reminder that in many parts of the country, including this section of rural southeast Texas, guns are woven into the history, upbringing and culture, and the relationship with guns gets passed down through the generations.

Parkland, on the other hand, is an upper-middle-class suburb in Florida’s Democrat-voting Broward County. It’s not uncommon for families to have a gun at home for protection, but most students don’t grow up learning how to shoot.

The contrast illustrates the obstacles facing gun control proposals in a country that is deeply divided over whether firearms are part of the problem of school shootings or part of its solution.

Drive two miles west from Santa Fe High School and you pass a sign just outside the town that advertises that Evans Farms Feeds sells “Guns & Ammo.” Across the street from a church that became a crisis center after the shooting, a home flies the Texas Revolution flag depicting a star and cannon with the defiant words “Come and Take It” beneath. Residents value self-determination and independence in a rural area they describe as “country” even as growth in surrounding communities is encroaching.

“I feel we just have to heal a different way,” Carvey said of the difference between the response in Santa Fe and Parkland. “Their way was to make a change, march. Our way is we just need time, we need time to process, to get everything together, to breathe and understand.”

We’re not huge gun people, but we’re not for gun control.

Jody Marabella, 56, a Santa Fe resident, said she doubts “our kids” will join in the gun reform activism that has swept the country since the Florida shooting.

“There may be a group, but I don’t think the majority will do that because, Santa Fe, we’re not huge gun people, but we’re not for gun control,” Marabella said.

One of the Santa Fe students who joined the small walkout against gun violence in March was Bree Butler, 18, a senior. After last week’s shooting, she posted a photo from the rally on Twitter and wrote, “It happened again.”

Still, Butler told USA Today that while she supports gun control, this is not the right time to protest.

“I know the political climate. I didn’t want to upset anybody,” Butler said. “Our community needs time to heal.”

One of the calls heard often in Santa Fe after the shooting is for teachers to be armed.

“It would definitely help if teachers were able to carry” guns at school, said Shannon Larsen, 33, a resident of nearby Clear Lake, whose 3-year-old son’s elementary school in Dickinson went on lockdown last Friday during the shooting. “That would help a lot.”

Some 170 school districts in Texas allow teachers to arm themselves. School boards can do so without state approval and can also determine the extent of training that teachers need. Separately, the state has allowed schools to select certain employees to undergo professional training and act as designated armed “marshals.”

Mass shootings can increase gun ownership. After a gunman opened fire in a church in Sutherland Springs, Texas, in November, gun license applications spiked in Wilson County, which includes Sutherland Springs, The San Antonio Express-News reported.

While residents of Santa Fe have largely shied away from debating possible solutions to gun violence since the shooting, elected officials have been more vocal.

Texas Gov. Greg Abbott, a Republican who is up for re-election this year, pledged to organize three roundtables on gun violence after the shooting and planned to hold the first one on Tuesday. He hasn’t committed to any specific proposals but mentioned a program used in the school district in Lubbock, in north Texas, designed to identify mentally unstable students.

State lawmakers pushed Abbott to hold a special legislative session on gun violence, since the Texas Legislature is not scheduled to meet again until next year. But with Texas Republicans in charge of state government, there’s little expectation that proposals to restrict guns will come from the sessions. In contrast, just weeks after the Parkland shooting, Florida’s Republican-controlled legislature passed a bill raising the purchase age for guns to 21, and Gov. Rick Scott signed it into law; Scott is the Republican U.S. Senate nominee challenging the Democratic incumbent, Bill Nelson, in November.

Texas State Rep. Chris Turner, who chairs the House Democratic Caucus, said in an interview with Houston Public Radio that he wants to see a range of issues discussed, including school security, mental health and access to guns. He also said that “until Republicans are willing to take on the NRA and say that ‘we’re going to pass laws that you might not like but that we think are in the best interests of protecting our citizens,’ then it’s going to be hard to move forward.”

There are some residents of Santa Fe who agree, though they often aren’t as vocal.

Solanda Miranda brought her grandson, Tyler, to the makeshift memorial created at the school. Tyler had been friends with Christopher Stone, one of the children killed in the shooting.

“I’m not for guns,” Miranda said. “It needs to stop.”

CORRECTION (May 23, 2018, 6:27 p.m. ET): A previous version of this article misattributed a quotation that criticized Republicans over their support for the NRA and called for a discussion of issues after the Santa Fe shooting. The remark was made by Texas State Rep. Chris Turner, not Rep. Jason Villalba.