It took two decades for Thomas Webb III to get Oklahoma authorities to pay for the nightmarish years he spent in prison for a rape he didn't commit.

The state finally agreed this week to write him a check for $175,000, according to his lawyers.

The payout is the maximum amount Oklahoma law allows people who have been wrongfully convicted to collect.

That is what is supposed to make up for his 13 years of incarceration ─ the lost wages and potential, the separation from family and friends, the time he'll never get back ─ and the psychological trauma that thrust him into addiction and homelessness after he was released.

And he's not allowed to ask for anything more.

But Webb says he will gladly sign the paperwork.

Simply getting the state to pay him, and in doing so acknowledge its mistakes, is enough to give him some comfort.

"For the first time, the state of Oklahoma has accepted the fact that I have been wronged," Webb, 56, said Wednesday. "That gives me closure, a feeling that justice, in my frame of reference, has been done, that amends have been made."

His journey, documented by NBC News last summer, has been epic.

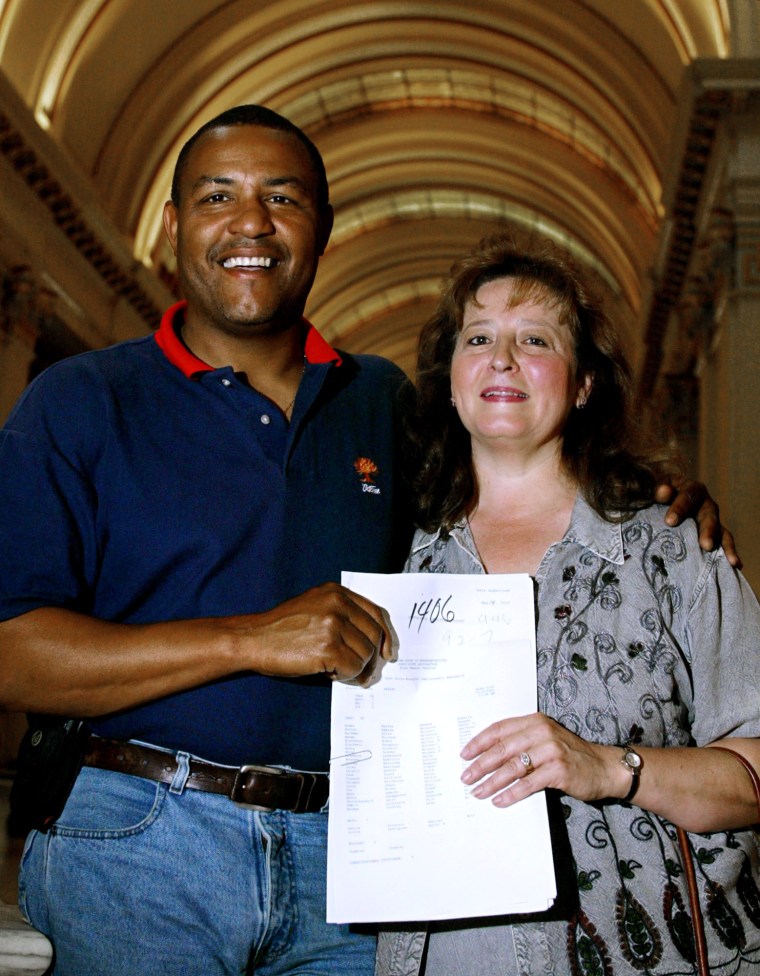

Convicted in 1983 of raping a student at the University of Oklahoma, Webb was exonerated in 1996 by DNA evidence that pointed to someone else ─ and proved that the victim had mistakenly identified him. He came home to a wife who'd married him behind bars and spearheaded his appeal. He found a well-paid job in computers. But his untreated emotional wounds led him to drink heavily.

While they struggled, Webb and his wife, Gail, lobbied for changes to the state Tort Claims Act that would allow compensation for people who had been wrongly convicted and imprisoned. Lawmakers twice passed a measure, and twice the governor vetoed it. Finally, in 2003, under a new administration, it became law, but the state capped payments at $175,000.

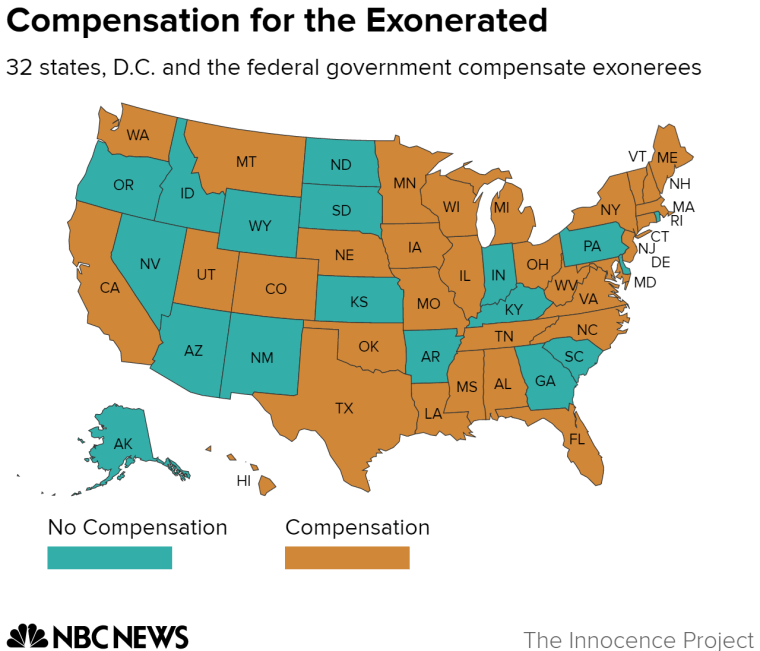

The law is stingy. Some states allow for millions in compensation. But several don't provide for any such payments. Webb was happy for the opportunity. He applied, and was denied.

Instead of appealing, Webb gave up. He turned to drugs, became homeless and divorced.

But he slowly turned himself around.

Early on in his recovery, authorities belatedly entered the DNA into criminal databases, and identified a suspect who'd raped a young girl while Webb was just starting his prison sentence. But the statute of limitations prevented authorities from prosecuting the man. He walked free.

Related: The Wrongful Conviction of Thomas Webb III

Around the same time, Webb was approached by his accuser, who apologized. He forgave her. To this day, she is the only person to say sorry for what was done to him. They became friends. He began to feel like he was healing.

He got in touch with the Oklahoma Innocence Project, whose founder, Lawrence Hellman, put him in touch a lawyer who could help continue his compensation fight. For months, through the end of 2016 and the start of 2017, Webb, Hellman and lawyer Rand Eddy pressed the state to reconsider the case. The state attorney general at the time, Scott Pruitt, did not respond. Then Pruitt left Oklahoma to become President Trump's administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency, and his replacement quickly approved Webb's request.

The confirmation came Tuesday. All that's left is for Webb to sign an agreement, a judge to approve it, and the check to arrive in the mail.

Hellman, dean emeritus at the Oklahoma City University School of Law, said Webb's story showed how far the justice system had to go to acknowledge the extent of wrongful convictions.

Last year, there were a record 166 exonerations, and there have been 2,000 documented since 1989.

Related: Number of Exonerations Hits Record for Third-Straight Year

"Now that society has accepted that innocent people get convicted, what the public hasn't focused on sufficiently is what happens to the people after they are exonerated," Hellman said.

Webb celebrated this week's news by telling his friends, including his accuser. But he also was afraid of getting too excited. He'd been let down so many times before.

"It's like an abused animal's reaction," he explained. "Even though the person is caring and has no intention of hurting you or anything like that, you still have reason to back off or be scared. That feeling is still there, still waiting for something to go wrong."

But it won't go wrong, Eddy said. The remaining steps are formalities. Webb will get his money.

The Oklahoma Attorney General's Office did not respond to a request for comment.

Eddy said the $175,000 "absolutely" falls short of what Webb lost. He'd like to see a system that allows juries to decide such compensation claims.

"I wish it could be more, but it still means a lot to him," Eddy said of his client.

Webb said he plans to use the money to repay his ex-wife for bankrolling his exoneration effort, and to pay back taxes, which will improve his credit and give him more financial stability.

He has become deeply spiritual during his recovery, and believes his path is being overseen by God. The compensation ─ the money and what it represents ─ is just another step, he said.

"But, hell, a public apology would have been the cheapest way to come to that," Webb said.

For that, he'll have to wait.