The USP Coleman II penitentiary in central Florida has long been known as a safe place for government informants and other marked men in the federal prison system.

But when James “Whitey” Bulger arrived in 2014, Charles Lockett, the warden at the time, wasn’t going to take any chances. He said he kept Bulger away from the general population for six months and talked to the most influential inmates to make sure they wouldn’t make a move on the elderly Boston mobster.

“He’s an old guy, but gangsters don’t forget,” said Lockett, who is now retired.

After four years at Coleman, Bulger, 89, was transferred to a prison in West Virginia with a much more violent reputation. Less than 12 hours later, he was found beaten to death.

Federal prosecutors on Thursday announced charges against three men, including a mafia hitman, in connection with the 2018 murder. But nearly four years after the killing, the Justice Department has still not shed any light on how the former mobster and FBI informant ended up in the general population of one of the nation’s most violent prisons.

“Although the defendants may be guilty of conspiracy to commit first-degree murder, the federal prison system also needs to be held accountable,” said Robert Hood, a former Bureau of Prisons chief of internal affairs and former warden at the ADX Florence “supermax” prison in Colorado. “The public needs to know why the BOP knowingly created a death sentence for Whitey Bulger.”

Hank Brennan, Bulger’s longtime attorney, filed a lawsuit on behalf of his family against the Bureau of Prisons in October 2020, alleging that the agency had failed to protect him.

The suit, which sought $200 million in damages, was dismissed in January. U.S. District Judge John Preston Bailey said in his ruling that federal courts were barred by Congress from weighing in on prison housing decisions that resulted in injuries or death.

Brennan said he believes the Justice Department waited to file the charges until after the civil suit was tossed to avoid having to turn over evidence that could aid the family’s case.

“They knew that a civil lawsuit could not proceed unless we knew who signed the transfer order, who directed and who approved putting him in a place where everybody knew he would be murdered,” Brennan said.

“They just don’t want this information to go to the public,” Brennan added. “And they don’t want to prosecute their own, and they never will.”

Stacy Bishop, a spokesperson for the U.S. Attorney’s Office in the Northern District of Virginia, rejected Brennan’s claims.

“The civil case brought by Bulger’s family had no impact upon the criminal investigation or the timing of the indictment,” Bishop said.

A spokesperson for the Bureau of Prisons declined to comment, saying it does not provide information related to investigations.

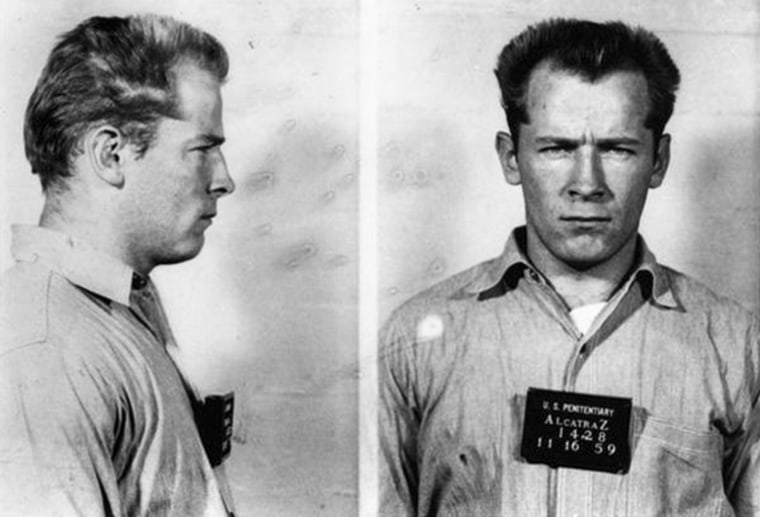

Known for his platinum hair and penchant for violence, Bulger ruled the streets of South Boston for decades. He disappeared in 1994 ahead of a looming indictment and evaded police for more than 16 years. But the infamous fugitive was captured in Santa Monica, California, in 2011 and ultimately sentenced to two life terms for his role in 11 killings.

He had no run-ins with other inmates at the prison in Coleman. But by the end of his time there, he used a wheelchair to get around and was dealing with heart problems and other health issues.

It remains unclear why he was transferred to the penitentiary in Hazelton, West Virginia rather than a prison medical facility. Known as “misery mountain,” Hazelton had a very different reputation than the facility in Florida.

Two inmates had been killed there in the previous six months, and prison workers were complaining of dangerous staffing shortages.

Bulger was wheeled into a cell just before 10 p.m on Oct. 29, 2018, prison records showed. He was found dead at 8:21 a.m., a couple of hours after the cells in his unit were unlocked so the prisoners could leave to eat breakfast.

Four inmates were immediately placed in solitary confinement. They included the three men who were ultimately charged — Fotios “Freddy” Geas, 55; Paul DeCologero, 48; and Sean McKinnon, 36 — as well as Bulger’s cellmate at the time, Felix Wilson.

Geas was serving a life sentence for murder and other crimes. He was an enforcer for the New England mafia during the 1990s and the early 2000s, according to federal prosecutors, making him a direct rival of Bulger, who was the leader of Boston’s Irish mob.

DeCologero was serving a 25-year sentence on racketeering and witness-tampering charges.

McKinnon was Geas’ roommate at the time of the killing, but he had no ties to the mafia. He was serving a seven-year sentence for stealing guns from a firearms store in Vermont.

All three remained in solitary for more than two and a half years as the investigation dragged on.

By the time the indictment was returned, DeCologero and McKinnon had both been transferred out of Hazelton. DeCologero was in a different prison; McKinnon was on supervised release in Ocala, Florida.

At his initial court appearance, prosecutors said McKinnon acted as a lookout while Geas and DeCologero repeatedly struck Bulger in the head, according to a transcript obtained by NBC News.

All three men were charged with conspiracy to commit first-degree murder. Geas and DeCologero were hit with additional charges: aiding and abetting first-degree murder, and assault resulting in serious bodily injury. McKinnon was also charged with making false statements to a federal agent.

Daniel Kelly, a lawyer for Geas, said his client’s indictment came as no surprise, but he didn’t expect it to take this long.

“What’s missing from the indictment here is the people who put Mr. Bulger in that position,” Kelly said. “They should be unindicted co-conspirators.”

It wasn’t known whether DeCologero had hired a lawyer. McKinnon’s lawyer did not respond to a request for comment, but he had previously told NBC News that McKinnon had nothing to do with the killing.

Alex Little, a former federal prosecutor, said the lack of answers from the federal government on the circumstances around Bulger’s transfer was likely due to the slow-moving criminal investigation.

The criminal investigators were almost certainly probing whether any Bureau of Prisons staffers deliberately placed Bulger in harm’s way as part of a conspiracy with prisoners seeking to kill him, Little said. And those investigators would not have wanted a report to come out with yet-to-be-disclosed details of how Bulger ended up at Hazelton while the investigation was ongoing.

“It would potentially bring to light pieces of the investigation that you’d otherwise like to keep quiet,” said Little, who is now a lawyer in private practice in Nashville, Tennessee.

The Justice Department Office of Inspector General has launched an investigation. Lockett, the former warden at Coleman, said he was interviewed by investigators a year after Bulger’s killing, but he hasn’t heard from them since.

A spokesperson for the inspector general’s office declined to comment on the status of the probe.

Lockett, for his part, said he still doesn’t understand why the elderly, ailing gangster had been transferred to the prison in Hazelton and placed in a regular housing unit.

“I would have never done that,” Lockett said. “And if I had input, I would have said, ‘No, no, no.’”