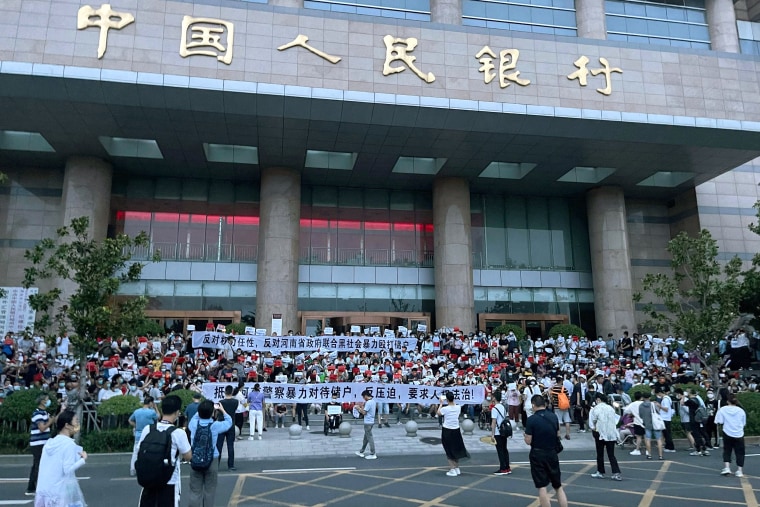

SHANGHAI — A woman who was injured on Sunday when a protest by roughly 1,000 bank customers in central China was violently broken up by security personnel said she continues to face harassment.

Still bearing bruises from kicks to her front and back, the 32-year-old woman, surnamed Geng, said she was awoken on Tuesday morning by loud knocks on her door from men claiming there was a water leak in her flat.

“I don’t know how they found me, they came to my house, but it’s under my mom’s name,” said Geng, who asked that only her surname be used given the sensitivity of the matter.

She said she threatened to jump out of the window if they tried to enter, then hid in her room for three hours as the two men in black, whom she could not identify, stood watch outside the apartment complex before she left from a different stairwell.

Other customers of the four small Henan province banks where at least $1.5 billion in deposits have been frozen since April have also reported harassment in a case that has dramatically exposed strains in a corner of China’s financial sector.

“It’s happened to a lot of investors — they want to wipe our phones, they want to take the videos and the evidence,” said Geng, who along with her mother had deposited 110,000 yuan ($16,354) at one of the banks.

Customers, who have grown increasingly assertive in calling attention to their grievances, told Reuters that police, village Communist Party officials and employers had visited them and their families in recent weeks to pressure them not to protest, including threat of job loss.

“The village party secretary will go to your house, will talk to your family and say that you’re making trouble,” said one, surnamed Chen, who said he was accused of being an overseas spy for speaking with foreign media.

After Sunday’s protest in the provincial capital, Zhengzhou, turned violent, police announced that they had arrested a number of accomplices in a scheme masterminded by Lu Yi, who they said used the banks to illegally siphon off money through a company he controls called Henan Xincaifu Group.

The statement did not say whether Lu was among those arrested. No one could be immediately reached at the group’s official email address for comment.

Police in Henan province and China’s Ministry of Public Security did not respond to requests for further comment.

While it is unclear whether the Henan bank troubles have wider ramifications, China’s thousands of small and midsize lenders are crucial to the domestic financial sector and have close linkages via inter-bank borrowing channels.

One depositor, who set up a WeChat group to coordinate efforts to retrieve their savings, said authorities had accused him of illegal assembly, causing what he said was “huge distress — bugging my sick mom, my wife, they’ve even gone to the school to find my kid, asking me to close the chat.”

Another, who works in a government finance department, was forced to resign after his attempts to join a protest came to light, according to screenshots of his resignation seen by Reuters.

Others said that when they travelled to protest destinations, police, Covid-19 prevention workers and others had repeatedly phoned them asking where they will stay and asking to meet. If they refuse, the calls can continue around the clock.

After being detained by police, customers have been asked to sign guarantees pledging not to protest, two of them said.

Last month, local authorities in Henan punished five officials for deliberately turning thousands of citizens’ health codes red, after depositors of the banks publicly alleged that their health codes abruptly changed from green to red when they began to travel to Henan to protest blocked withdrawals.

ANZ Research said that because high-risk institutions account for just 1 percent of Chinese banking assets, the problems at the Henan village banks were unlikely to spread to the wider banking sector.

Still, ANZ said, “despite the small size of the assets involved, the social impact of the incident could be significant if it is not handled appropriately. It could also trigger another round of regulatory tightening.”

China acts quickly to quell protests that could cause unrest or challenge the legitimacy of the ruling Communist party, and the space for dissent has narrowed under President Xi Jinping.

This week, China’s banking regulator said that Henan and Anhui provinces will start repaying some of the funds to customers with savings of under 50,000 yuan ($7,435) at rural lenders including Xinminsheng Rural Bank and Shangcai Huimin County Bank.

But many customers have much larger sums frozen, and the notice from the banking regulator does not characterize the funds as deposits, which the customers worry could limit their ability to be made whole.

China’s banking regulator, the central bank and the Henan lenders did not respond to requests for comment.

Many depositors say they plan to continue their protests.