There still may be places on Earth that aren’t despoiled by man-made trash, but they aren’t in the deepest reaches of the world’s oceans.

A plastic bag near the bottom of the Marianas Trench is just one of many bits of garbage that foul even the most remote points beneath the Earth’s seas, Japanese scientists recently revealed.

In a paper released last month, the researchers cataloged 3,425 cans, bits of plastic and stray fishing gear captured in photos and videos taken by deep-sea submersibles and remotely operated vehicles, mostly in the Pacific Ocean.

The images prove that “the influence of land-based human activities has reached the deepest parts of the ocean in areas more than 1,000 kilometers from the mainland,” the scientists said.

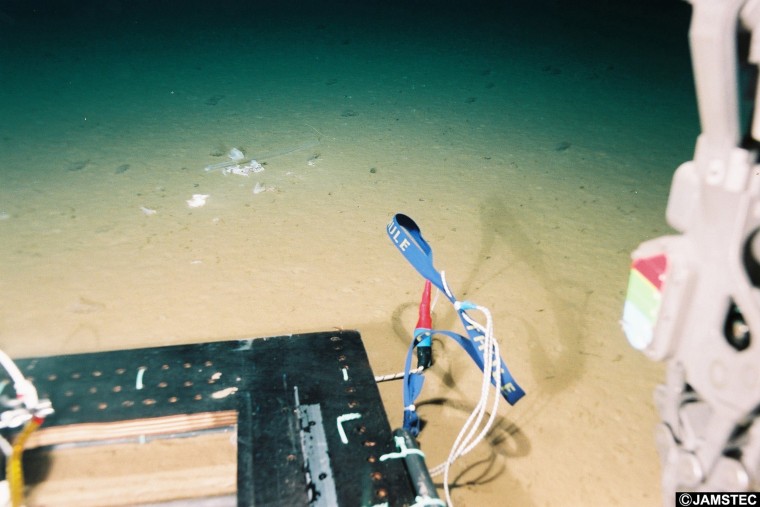

A remote vehicle captured the picture of the stray plastic bag at 35,775 feet beneath the surface, in one of the deepest sections of the storied trench, which stretches for more than 1,500 miles in the far western Pacific Ocean.

The review also found that the majority of humankind’s waste found at 18,000 feet and below comes from “single-use” products — the plastic bags and containers that many communities have begun to outlaw.

The startling find near the ocean’s deepest point reinforces earlier research that has shown vast swirling patches of plastic in the oceans. Dubbed garbage patches or “gyres,” much of the waste in the floating trash fields is too small to be seen, but pervasive and toxic enough to do widespread damage to sea life.

While near-shore pollution and the mid-ocean trash fields have been well documented, the Japanese researchers said less has been reported about the impact humans have had in the deep sea.

To study these dark zones, they made a comprehensive review of images collected over 35 years by Japan’s Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology. The information came from more than 5,000 dives. The scientists found that one-third of the human debris in the depths was “macro-plastic," or larger objects like plastic bags. The researchers said more study is needed to understand how the plastic and other waste gets from land — where most of the garbage is suspected to originate — into the deep.

Their findings, “Human footprint in the abyss: 30 year records of deep-sea plastic debris” were delivered in the journal Marine Policy.

The paper was not the first to suggest trouble in some of the Earth's most inaccessible places. A 2016 study revealed the presence of extremely high levels of toxic PCBs in tiny crustaceans that live in the Marianas Trench. Though banned in the 1970s, the chemicals don’t break down in the environment and accumulate in the fat of sea creatures.

Experts in America said the latest findings should renew concern about the threats to the world’s oceans.

David Gallo, an oceanographer who spent two decades at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts, said people tend to view the ocean as so vast that it can absorb multiple assaults by mankind.

But while oceans cover 70 percent of the Earth’s surface, Gallo said that the total volume of water represents “about the size of a pingpong ball in volume, if the volume of the Earth was represented by a basketball.” He added: “We trick ourselves [that] there is a lot of water, but there is really not a lot of water.”

Gallo said the new findings are a grim confirmation of what he has seen since his first research trip into the Pacific in the 1970s. “I thought we would be venturing into something like an alien planet, where there had never been sunlight,” Gallo said. “Then we get to the bottom and, lo and behold, one of the first things we see is a brightly colored piece of plastic.”

Mark Gold, a UCLA ocean scientist who previously led the environmental group Heal the Bay, said decades of work in ocean cleanup has persuaded him that governments need to take more forceful action. He once believed that recycling and cleanup programs could rid much of the ocean pollution. But he has concluded that only a ban on some plastic products will make a serious dent in the problem.

“We still have 8 million tons of plastic a year going into the ocean,” Gold said. “Anything short of putting bans on single-use plastic packaging is not going to solve the problem. What we have done so far is just reduce the rate of magnification. But the problem is still growing.”