SEOUL, South Korea — The pandemic has made us all face decisions we’ve never had to make. For me, one of them was to decide if it was safe enough to visit my parents here or not see them at all this year. But as the weeks extended to months, I decided it was a risk worth taking.

Many countries have strict restrictions on American visitors, with many requiring them to spend two weeks in quarantine. South Korea was no exception: I was told I would be required to download an app at the airport and self-quarantine for two weeks on arrival.

But that was just the beginning. It wasn't until I arrived that I realized the extent of the government’s program to contain the virus.

At Kennedy Airport’s international terminal in New York, normally filled with lines of people heading to destinations across the world, all was silent. Check-in counters were empty and the floors looked as though they had been polished minutes ago.

The check-in assistant was friendly and the process was seamless until she handed me a piece of paper I needed to sign acknowledging that I would in quarantine for 14 days at a government facility on arrival. I explained to the airline agent that I had planned on staying with my parents.

The agent informed me that without proof my parents live in Seoul, I would be shuttled straight to the government facility from the airport in Korea. I called my parents in a panic, though it was 2 a.m. there. Luckily they had the required forms lying around from a few years back. They sent me a screenshot of the document, which I hoped would be enough when I landed.

LANDING IN KOREA

Korean Air, like many other U.S. airlines, had spaced out seats throughout the plane to adhere to social distancing protocols. While on the plane, I was handed four pages of forms to fill out, which included three different travel declaration forms and an arrival card, rather than the usual single form.

By the time I landed at Incheon Airport, everything felt sterile. Video walls once lined with “Welcome to Korea” advertisements were replaced by videos of dancing sharks advising people how to keep clean and safe during the pandemic. It appeared I had traveled on the only plane that had arrived at the terminal.

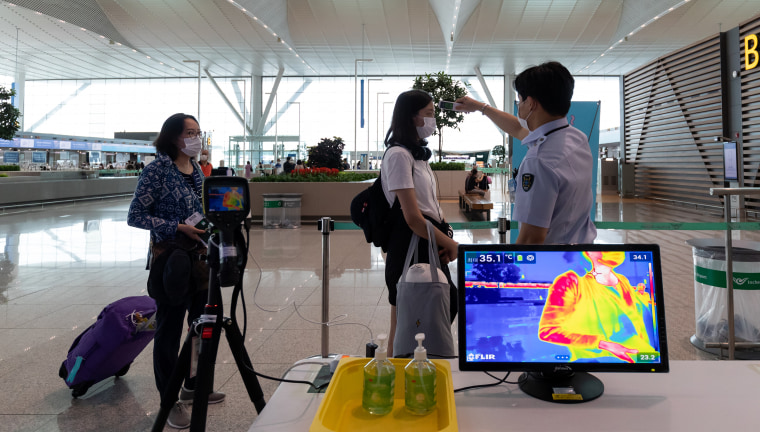

The first desk we passed while going through the terminal, which we would normally bypass, had a mounted heat sensor camera. I was stopped and asked a few questions and had my temperature checked.

I gave my U.S. cellphone number, but was told I needed to provide a Korean one. I crossed off mine and replaced it with my mom’s cell number. They were meticulous in examining the details I had jotted down on all my forms.

At the next checkpoint, I was told to download the Korean government’s Covid-19 app, titled “Self-Quarantine Safety Protection.” It had a tracking device and I would need to record my temperature and any symptoms twice daily. The assistant hovered over me and watched me as I installed the app on my iPhone just to make sure I had enabled alerts and that the app was running at all times.

Download the NBC News app for full coverage of the coronavirus outbreak

At the third checkpoint, I handed over my passport and travel documents before another clerk confirmed my app was indeed downloaded properly. They then called the Korean number I had jotted down earlier to confirm it worked.

I was then handed another three pages of forms to fill out, before staffers at two further checkpoints verified the information. This is how it’s determined whether travelers need to quarantine. Failure to comply could result in up to a year in prison or up to 10 million won (nearly $9,000) in fines, per the Korean Disease Control and Prevention Agency.

The last checkpoint before baggage claim was, among other things, to verify my parents’ information so that I could stay with them. Because of the documents I hastily gathered right before my flight, with just a screenshot of a piece of paper from years ago, I would be exempt from quarantine. If the information couldn’t be verified, I would be taken straight from the airport to a hotel and ordered not to leave for two weeks.

Finally, I thought I was on the other side. I was jet-lagged and I wanted to see my parents and go home. But there would be one more line. Visitors are normally required to travel into Seoul by a government-certified taxi or shuttle bus.

But my parents would be driving me home, which meant surrendering yet more information, this time providing my father’s cell number and our home address.

STAYING IN KOREA

The next morning, I was required to take a Covid-19 test. Whether you are a foreigner or a Korean citizen, the tests are walk-ins and they’re free. As I waited for my turn, I overheard a group of men say they had received an alert about a case at a wedding they had attended. It was incredible seeing this contact tracing we’ve all become so familiar with happening in real time.

Later that night, my mom received a text from the local agency to say my test was negative. I would also be assigned a case agent who would be my contact during my stay.

A bag arrived from the local authority the next day that contained a thermometer, a pack of disposable masks, two types of hand sanitizers and a garbage bag. For the two weeks of my quarantine, I would need to discard any of my garbage in the government-mandated bag. I was told it would be collected at the end of my stay.

On day seven of the quarantine, my mom received yet another call from my appointed Covid-19 contact. They wanted to speak with me. I was asked to confirm that I was, in fact, me, before asking some questions and offering mental health services if I required one.

Whenever a new case emerged in a neighboring town, my iPhone would ping with a new notification, the same noise phones make when there is an Amber Alert in the U.S. I would get two or three of these alerts almost every day.

LEAVING KOREA

The day before my flight back to the U.S., my local contact wanted to confirm my flight details. She also reminded us that I would need to take those government-designated taxis to the airport, despite having been able to ride along with my parents when I had landed. The taxis were meticulously sterilized after each ride.

Being able to walk around an airport felt freeing after two weeks stuck inside. Life was back to normal — people sat and ate at tables, which had been roped off so we’d be socially distanced. We shared elevators. Stores were open but foot traffic was low.

LANDING BACK HOME

It’s hard to imagine the U.S. being able to implement all the measures used in South Korea. Americans have been reluctant to set aside their privacy and freedom to requirements of safety and control. South Korean culture is more conservative, a view shared more widely in Asian cultures with emphasis around respecting the elderly that perhaps trickles down to how people view authority.

On my plane home, I received one pamphlet from the CDC. “Stop the Spread of Covid-19: Do your part. For 14 days after your trip, stay home. Monitor your health.”

With that, I landed back at JFK. No paperwork, no app, no temperature checks. I took an Uber which I booked from my iPhone, and went home.