SUMTER, S.C. -- A niece of one of two young girls murdered in South Carolina nearly 70 years ago testified Wednesday that the conviction of a 14-year-old boy executed for the crime should stand, saying, "I think that it needs to be left as is."

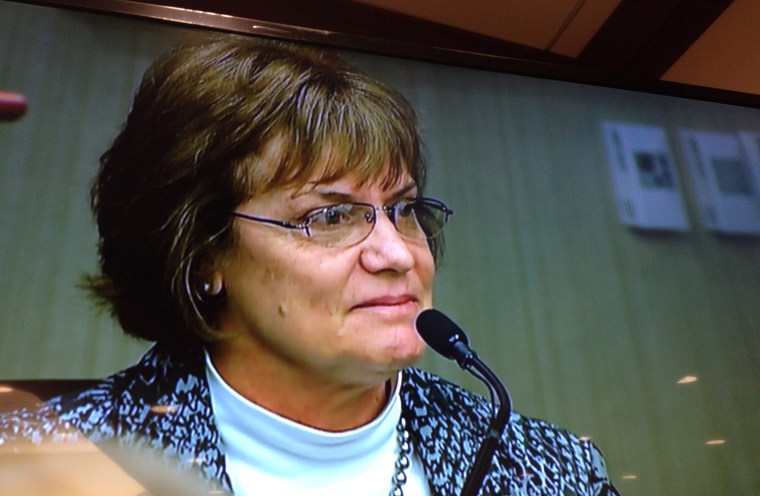

Frankie Dyches, whose aunt, Betty June Binnicker, 11, was one of two girls killed on March 23, 1944, in the small mill town of Alcolu, S.C., took the stand to oppose granting a retrial for George Stinney Jr., the young African American put to death for the crime.

She said her family has long considered the case closed.

"We always knew that our aunt was murdered and we always knew that it was George Stinney Jr.," Dyches said of the youngest person executed in the United States in the past century. "My grandparents to begin with never recovered. That was their baby daughter."

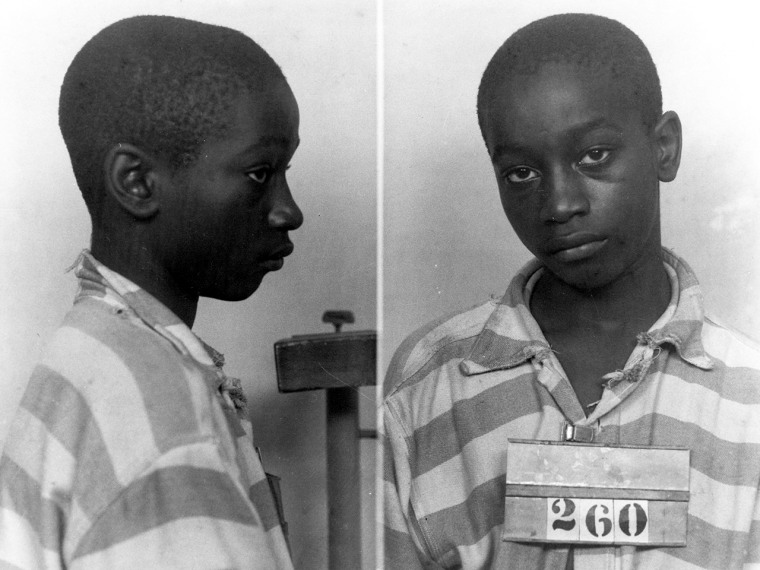

Stinney's family is asking Circuit Court Judge Carmen Mullen to order a retrial for Stinney in hopes of clearing his name. Two of Stinney's sisters and a brother testified Tuesday that the teenager spent the day of the girls' disappearance with the family and could not have committed the crime.

After Dyches' testimony on Wednesday, Mullen adjourned the hearing without immediately ruling on the request. She said she would give state prosecutor Ernest "Chip" Finney III 10 days to review legal issues discussed during the hearing, specifically a legal brief introduced only a couple days, written by a law professor hired by the defense. Her ruling would come at some point after that.

Dyches testified that her family, including her mother, who died six months ago at the age of 90, had long ignored discussion about the case and accusations that Stinney was railroaded for the deaths of Binnicker and Mary Emma Thames, 7.

"This has been coming up back and forth for as long as I can remember and we never responded to anybody because we just thought … it would go away," she said.

But she said she could no longer remain silent when she heard rumors that her grandparents – Binnicker's parents – had accepted cash in exchange for protecting the identity of the true killer.

"When somebody told me that my grandparents had taken money -- to shut them up and be quiet -- and that they knew the true murderers, it's when I got mad,” Dyches told the court. “… My grandparents were as poor as church mice. They worked in that lumber mill and they picked cotton. And to even suggest that they even took money, no, do not tell me that."

Earlier Wednesday, Dr. Amanda Salas, a child psychiatrist trained as a forensic psychiatrist, testified for the defense, saying that Stinney's alleged confession -- in which he reportedly told police that he had killed the girls with a railroad spike -- could not be trusted.

"It is my professional opinion, to a reasonable degree of medical certainty, that the confession given by George Stinney Jr. on or about March 24, 1944, is best characterized as a coerced, compliant, false confession," she said. "It is not reliable."

After a trial that lasted less than three hours, an all-white jury deliberated just 10 minutes before convicting Stinney. His court-appointed attorney did not appeal the conviction, and George was executed in the electric chair less than three months later.

Advocates for Stinney and his family say that newly discovered evidence -- and a timetable suggesting a rush to judgment by the court in 1944 -- justify reopening the case, even though there is no legal precedent for doing so.

Mullen cautioned the audience in the crowded courtroom at the outset that the hearing would not lead to a decision on whether Stinney was innocent or guilty, only "determine if he received a fair trial."

Three of Stinney's surviving siblings testified Tuesday that their brother spent the day that the girls vanished with his family and could not have killed them.

"They said he killed those girls and I knew that was a lie," one sister, Amie Ruffner, testified, referring to police assertions at the time that George had confessed to the crime.

"The evidence here is too speculative and the record too uncertain for the motion to succeed," he said.

Ruffner recalled hiding in the family chicken coop when police arrived at the house and took George and his older brother, Johnnie, away for questioning. Johnnie Stinney was later released as officers focused on George, who with his younger sister was the last person known to have seen the girls alive.

“They took my brothers away and I never saw my mother laugh again,” Ruffner said simply.

Ruffner said the rest of the family fled the town soon after, fearing retribution from townspeople.

“Daddy said we had to get out of here,” she said. “We were afraid for ourselves.”

Also testifying Tuesday were Stinney’s sister, Katherine Stinney-Robinson, and a brother, Charles, both of whom testified that George had been with the family that day. Charles Stinney testified in a taped video interview because he was too ill to travel to South Carolina from his Brooklyn, N.Y., home.

Arguing against reopening the case, Finney told the court in opening statement that because most of the evidence in the case has been lost or destroyed, there is no way to establish that Stinney's trial was unjust.

The proceedings grew tense briefly when Finney challenged Ruffner on whether her memory could be trusted after was unable to recall whether if she had written a notarized account from 2009 laying out her memories of the days surrounding the crime.

Related: Advocates push for retrial to clear name of 14-year-old 'killer' executed in 1944

“If you can't remember what you wrote in 2009, how do you expect us to believe that you remember what you did in 1944?” he asked.

An agitated Ruffner raised her voice and answered, “Because I was alive in 1944!”

Todd Johnson of The Grio contributed to this report.

More from NBC News Investigations: