JERUSALEM — The highway that critics dub "apartheid road" carves a path from the outskirts of Jerusalem north into the occupied West Bank. A fence tops the high concrete wall running down the middle of Route 4370, slicing the thoroughfare in two: The far lane is for Israeli-registered vehicles, the other for Palestinian traffic that is banned from entering Jerusalem.

“They say to themselves it is about security but it looks very bad,” activist Shabtay Bendet says as he perches on a nearby rocky hill, referring to Israeli officials' reasoning for the segregated highway.

The road will hasten the growth of Jewish settlements on land Israel seized in the 1967 war with its Arab neighbors, concludes Bendet, 46, who sports jeans and small silver hoop earrings.

It wasn’t so long ago that he wore a bushy beard and the black garb favored by hardline ultra-Orthodox settlers. And in those days, he would most certainly have supported the highway. Now he plays cat-and-mouse with aspiring and established settlers for Peace Now, a decades-old group that advocates for a two-state solution.

Bendet's dramatic transformation saw him cross a chasm dividing Israeli society: From fervent believer that God commands Jews to settle “Biblical Israel” to someone who sees settlements located beyond the borders set when the country was founded in 1948 as a threat to its existence as a democratic state.

Bendet turns away from the road and heads back toward his car where the baby seat belonging to his 9-month-old son, Carmel, nestles in the back seat. His child shares a name with Mount Carmel in northern Israel. Carmel is a word resonant in both Hebrew and Arabic, suggesting a freshly planted garden — an indication of Bendet’s hopes for the future.

'I started understanding'

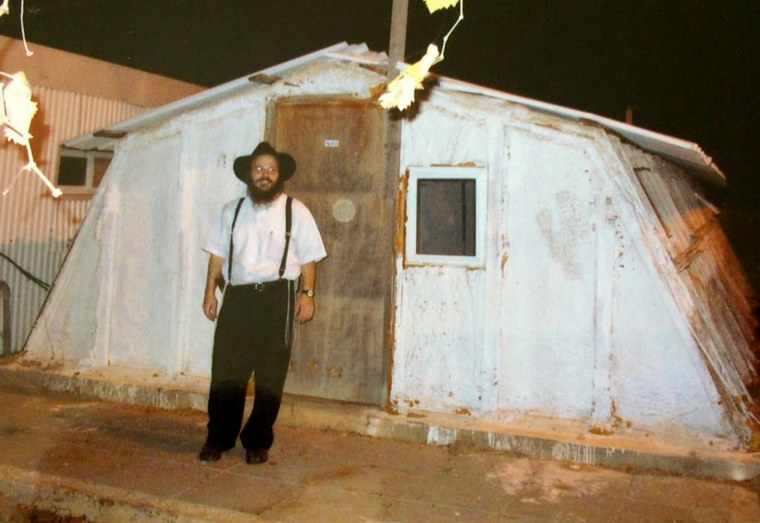

Bendet was a co-founder of Rehelim, one of the West Bank’s first illegal outposts.

He moved a growing family there — he eventually had six children with his then-wife — and helped sneak covert trailers into the settlement to lay claim to the hilltop near the Palestinian city of Nablus.

Then 15 years ago he began suffering a crisis of faith. By 2007, he stopped being religious.

“My belief and ideology were together; when I stopped believing, I started researching my ideology,” Bendet says as he drives his car on a tour of West Bank settlements — communities most governments deem illegal because they are built on occupied land.

The more he researched, the more he changed.

“I started understanding Palestinian people, started understanding what we were doing to them when we built an outpost,” Bendet says as he smokes one of many roll-ups.

The Tel Aviv native says he questioned his most basic assumptions. Bendet later became a journalist covering the West Bank.

And now as the head of Peace Now's Settlement Watch division, he keeps track of communities like the ones he fought to set up.

Bendet believes that not only do settlements pose a threat to the existence of the state of Israel, they also help hold millions of Palestinians under occupation and without rights.

It wasn't supposed to be this way. Some 25 years ago, hopes ran high that the Oslo Accord signed by Palestinian and Israeli leaders would lay a foundation for peace through two states living side by side. Since then, on-off peace talks have foundered and violence has flared.

In Israel, intermittent Palestinian terrorist attacks coupled with the Israeli withdrawal from the Gaza Strip, which was swiftly taken over by Hamas, have caused widespread disappointment and raised fears of a similar move in the West Bank.

And settlement activity is booming with roads dividing up the land making an independent Palestinian state an ever-fainter possibility — something Bendet feels is deeply unfair.

"We fought for a country 70 years ago — a country for Jews," he says. "I don’t understand why we don’t give Palestinians what we struggled for before."

Dreams of independence

In February 2017, when he was still a journalist, Bendet visited Amona — another outpost being evacuated because Israel's Supreme Court ruled it had been built on private Palestinian land.

While there, he confronted his two oldest children — a son and a daughter who are now in their early 20s — among hundreds protesting the eviction.

Eventually, the demonstration was broken up. As his son was carried away by soldiers, Bendet followed with the young man's duffel bag.

Bendet's change in life is not easy for some of his kids; after all, he raised them to be settlers. So he knows uprooting settlements — something essential to building a Palestinian state — will be deeply painful for some Jews.

“Nobody in my office is glad when we succeed in removing illegal houses,” he says.

With settlement activity reaching record levels in the last two years, the situation is now acute, Bendet believes.

The population of settlements is growing faster than the population of Israel as a whole.

Last month, a West Bank settler group reported the number of people living in the settlements grew by 3.3 percent last year. The country's overall population growth rate was 1.9 percent.

.

Meanwhile, official proposals for the building of housing units, or tenders, have rocketed from 42 in 2016 to 3,154 the following year and 3,808 in 2018, according to Peace Now figures.

Bendet surveys Givat Eitam, a Jewish outpost south of Bethlehem that is a handful of buses, trailers and long tent sitting on a bare plot of earth.

“The view is so beautiful but when you start to understand what is going on here, you understand it is not beautiful at all,” Bendet says, adding that the development of the location would likely strike a blow to a contiguous and independent Palestinian state by cutting off communities from each other.

“All the Palestinians see the dream of building a state going away,” he adds.

Withered fruit trees

Ali Musa's American-accented English is a legacy of old hopes of winning a degree in U.S. literature. Those plans were derailed in 1999 when Jewish settlers occupied his family’s farmland.

The beginning of his relatives' fight coincided with the Second Intifada, or Palestinian Uprising, which left around 3,000 Palestinians and around 1,000 Israelis dead.

The 52-year-old now works as a mechanic in the shadow of Efrat, a large settlement near Bethlehem.

The Musa family's struggle, as they and activists tell it, features arbitrary detentions, police and settler violence, intimidation and close to $6,000 spent on legal bills.

“I sold many things to pay for my fight, including my wife’s gold,” Musa says as he sits beneath a leaky blue tarp that covers the car repair shop. Bendet sits nearby on a maroon sofa — a steady drip of water soaking the upholstery.

Bendet and Peace Now work with the Musas to help them reclaim land that is now the Jewish outpost of Netiv HaAvot, helping navigate what the group describes as a dizzyingly complicated process.

Over the years, Musa says he has seen fruit trees wither from neglect because his family could not reach the land to care for them. He’s also watched settlers' trailers multiply and morph into buildings.

“I’ve hidden my feelings — like how I deprived my kids, giving all my money to the lawyers,” he says.

In June, the Musas greeted what should have been a victory: Security forces began evicting settlers from 15 Netiv HaAvot buildings after a Supreme Court ruling that it had been built illegally on private Palestinian land.

The move drew hundreds of angry Jewish protesters who flew Israeli flags. Scuffles broke out. Some 20 houses on land not covered by the ruling were granted legal status and designated a neighborhood of an Israeli government-recognized settlement.

Now the case is still winding its way through the system, so there is still no closure for Musa and his family.

The day before NBC News visited Musa, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu stopped in Netiv HaAvot to lend his support to settlers fearing they would be forcibly moved. He also called the court-ordered demolitions “a mishap.”

Netanyahu is a close ally of President Donald Trump, whose administration has been less critical of Israeli settlement policy than that of former President Barack Obama.

Bendet muses that many well-intentioned Israelis do not know how bad life is for many Palestinians in the West Bank.

“A lot of people think, ‘Wow, we give them work.’ They think, ‘They love us,’” he says. “But they don’t think about how a Palestinian needs to work to give food to his family because his house was taken from him.”