KOENIGSWINTER, Germany — Seventy-five years after D-Day, the world is once again a troubling place to a former German soldier who was on the losing side of the cataclysmic clash that hastened the end of World War II.

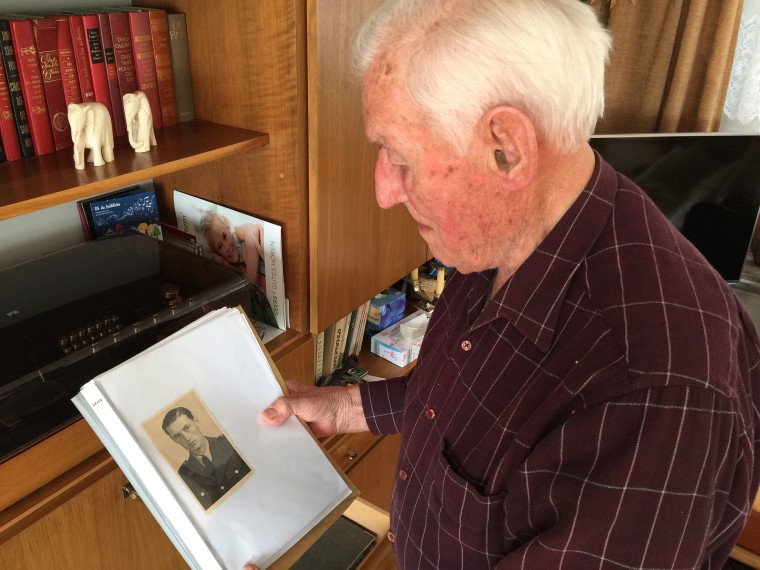

Paul Golz, 95, has a clear memory of being on guard duty in the early morning hours of June 6, 1944 — and realizing the invasion was underway when the skies over the Normandy coast were illuminated by flares, known as “Christmas Trees," dropped by Allied planes to mark paratroop landing areas.

“It looked very nice,” Golz, sitting in his tidy cottage in the German town of Koenigswinter, told NBC News several months before the anniversary of D-Day. “And then I knew, aha, now it is starting.”

Golz was at the time a drafted member of the German army, then under control of the Nazis, and he has recounted that day several times before to historians, to curious reporters, and to several generations of school children.

But as the leaders of the Free World prepare to mark the 75th anniversary of D-Day, Golz said he fears a fraying of the alliances that were created in the wake of the war, alliances that brought peace and stability to Europe. And he has deep misgivings about the leadership of President Donald Trump.

“With Trump it is not easy,” Golz said. “Many Germans are not happy with what he does. He cannot just say ‘America First.’ Today you cannot succeed alone.”

It’s not just Trump. Britain’s decision to leave the European Union also worries Golz.

“Take Brexit, that monkey business. How should England succeed in a world where everything is globalized?”

Paul Golz

“Take Brexit, that monkey business,” he said. “How should England succeed in a world where everything is globalized?”

Like many Germans, Golz also takes a dim view of the thousands of Syrian refugees who have recently found shelter in his country.

“Nobody wants them, we also do not want them to stay,” Golz said. “We rebuilt our country, the Syrians also have to go back and rebuild their own country. There is no other way.”

Never mind that Golz himself became a refugee after the war when Pomerania, a region on the southern Baltic coast where his family ran a farm, was returned to Poland and the Germans were expelled.

What remains undimmed by the passage of time, however, is Golz’s belief that the invasion that spelled the end of the Third Reich saved Europe — and his life.

“It changed my life, the life of a poor farmer’s son,” Golz said in German. “I am thankful to the Americans, too. I was never treated badly. We always had enough to eat. And we had these great windbreaker jackets.”

Were it not for a case of diphtheria, Golz might have wound up on the Russian Front. He came down with the infection not long after he was drafted at age 18 and wound up in a hospital in the German-occupied Polish city of Torun.

“Approximately 10 people from my company were ill at the time, and most of the others were quickly deployed to Russia,” he said. “They died like flies. Hitler sent the youth to the slaughter.”

Once he was better, Golz was assigned to 91st Air Infantry Division and dispatched to Normandy where the troops were literally dug in near the Cherbourg heights.

“We did not live in houses at the time, but dug holes where we lived,” he said. “About one meter deep into the ground and a tent above it. We were about eight people in one tent.”

And all around them was a forest of “Rommel’s asparagus,” millions of 13-to-16-feet logs planted in fields, the tops connected by tripwires that would set off a mine should a parachutist or a glider hit one. They were named after Field Marshal Erwin Rommel.

On the day of invasion, Golz said he was more concerned about being hungry than the invading Allies. He said at that point he had not eaten in three days, but when he went into a nearby village to get some milk he was rebuffed by the French.

Golz said he returned to his unit, which had been ordered to march toward the town of Sainte-Mère-Église, some three hours away. But en route, Golz said, they were ordered to head to another town.

“I saw how the bombs were dropping,” he said.

Starved and thirsty, Golz said at one point he wandered off into a field in search of sustenance when he saw something moving.

"I took my weapon down and moved toward it," he said.

It was a downed parachutist. His face was covered with camouflage paint, but he was unlike any man Golz had ever encountered before.

“I had never before seen a black man,” Golz said.

Golz said the soldier was trembling. He said he spoke no English, so he tried to reassure him in German that he was not going to hurt him.

“He spoke back to me calmly in English and in the end took his water bottle and said ‘Good water,’ which I understood,” he said.

Golz said he insisted the soldier take a sip before he too drank from the bottle. Then he took the American prisoner.

The next day, Golz said he saw his first dead American. He said the German soldier he was with, a Saxon named Schneider, began searching the pockets of the corpse and found a wallet with a picture of a pretty blonde woman inside.

“And then we saw that he had a golden ring with a stone on his right hand,” Golz said. “Schneider tried to pull it off, but could not get it off. So, he said he would cut off his fingers. I said, ‘If you cut off his fingers, I will blow you away.’”

“It was good that we did not do it,” he added. “Because we heard from others that if the Americans found a ring on you, they would shoot you.”

By June 10 of that year, the war was over for Golz. He said after strafing a column of American trucks with machine gun fire, they retreated to a pasture where the pursuing GI’s found them.

“Come on boys, hands up,” Golz recalls the Americans telling them.

Golz said they had no choice but to surrender. He said they were forced to march for two hours to a market hall where about 100 other German prisoners of war were being held. He recalled that the black GI guarding them rebuffed a furious French man who wanted to shoot all the Germans.

“The American had a duty to guard us, and that is what he did,” Golz said.

From there, the POWs were marched to Utah Beach and loaded on a British ship. To this day he remembers in detail what they were fed.

“Sausages, mashed potatoes, a cup of coffee and white bread,” he said. “After we ate, we were still hungry, so we went down the stairs and stood in line again to eat a second time.”

They were taken first to a prisoner of war camp in Scotland. Then, after a time, they were shipped across the ocean to New York City on a ship called the Queen Mary 1. From there, Golz said they were taken by train to West Virginia and a POW camp where they were treated more like guests than prisoners.

“On every bed there were cigarettes and chocolate, and they had prepared food in the kitchen for us,” he recalled, smiling broadly. “That is where I drank my first Coca-Cola. Wow, that tasted delicious. Ice cold.”

Just how well they were being treated sank in for Golz when they were made to watch news footage from the newly liberated Nazi concentration camps.

“It was the first time we were confronted with the atrocities,” he said. “We saw the starving people in the concentration camps.”

Golz said that, when he was asked at age 16 which branch of the service he should sign up for, his older brother, who had already fought in Ukraine, had advised him not to join the Gestapo.

“They did not fool around, I was told,” he said.

But Golz said he was not aware of what his fellow Germans had done to the Jews and Poles and countless others until he saw the footage. He said his captors were surprised when he told them he did not know what happened in places like Auschwitz, Dachau or Sachsenhausen.

“I told them I did not know about this because in Germany we did not get to see or hear this,” he said. “Those who had taken part, had been a guard there, did not say anything.”

Golz said he was released in 1946 and when he returned to what was left of Germany he began to realize how lucky he was to have been captured by the Americans. In addition to losing his home, he learned that his sister had been raped by Russian soldiers and became pregnant.

“The worst I did not get to see because I was in the United States at the time,” he said.

In the years that followed, Golz said he became a student of the war he had taken part in. He began returning to Normandy on the significant anniversaries and meeting with American soldiers who were once his enemies. He recalls being deeply moved the first time he went to the American cemetery.

“They were all shot in the water on June 6,” he said. “That was on my mind when I saw the many graves. The Germans sat in a big bunker with big machine guns and just aimed at them.”

Golz said he was also asked several times to speak to French schoolchildren about the war and his small part in it. He showed a reporter the words he used to read to the classes when he made his presentation.

“These many, many young men, most of them between 18 and 25, have given their lives for our peace, for today’s Europe,” part of it reads. “Remember that and preserve this peace.”

In the twilight of his life, Golz said he is aware that he is part of a dwindling fraternity and that time has done what the bullets didn’t do in 1944, namely cull the numbers of men he could call comrades-in-arms.

These days, when he can, Golz said he tends to his little garden and the old apple tree that “still brings him joy and a few apples each year.” And he remembers.

“I have no hate, no hate,” he said.

Eckardt reported from Koenigswinter, Germany, and Siemaszko from New York City.