MOSCOW — Russian President Vladimir Putin's approval rating has not dipped below 80 percent in years.

And yet police detained more than 1,000 people in Moscow on Sunday during an unexpected surge of street protests that spanned 82 Russian cities — with demonstrators carrying sneakers, rubber ducks and painting their faces green.

So what caused this mass dissent in Putin's Russia?

The protests follow allegations against Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev that stem from a high-profile expose published earlier this month by opposition leader Alexei Navalny.

His report alleged that one of Medvedev’s estates features a duck house built in the middle of a pond.

It also painted the prime minister as a compulsive online shopper, ordering 73 T-shirts and 20 pairs of sneakers in just three months.

The demonstrators noted this alleged opulence by carrying ducks and sneakers during Sunday's marches.

Some also painted their faces green in solidarity with Navalny, after unidentified attackers threw green antiseptic at him last week. The substance takes days to wash off and Navalny has been sporting a green face for some time.

But what will all this mean for Putin's government, an administration opponents accuse of being anti-democratic kleptocracy built on corruption and the silencing of dissenters? Here are seven key questions answered.

1. First of all, what happened?

Demonstrators gathered in dozens of cities to protest against alleged corruption by Medvedev, who was once president of Russia and remains a close ally of Putin.

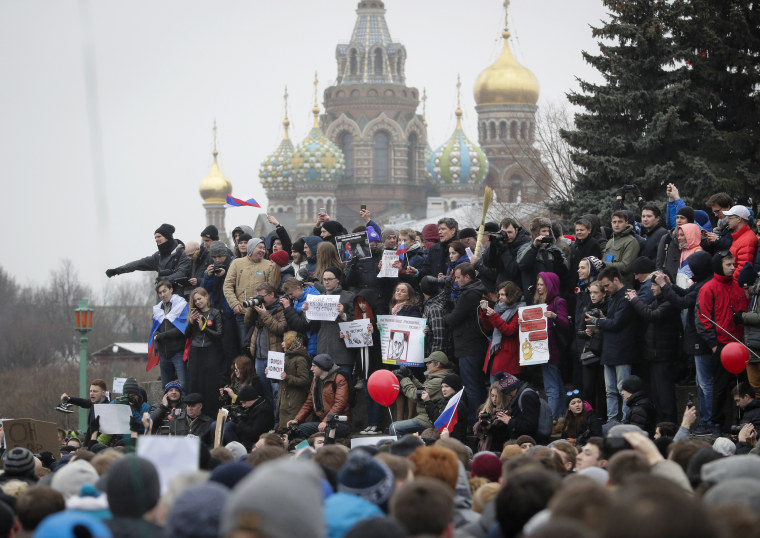

The liberal radio station Echo of Moscow estimated that 60,000 turned out across the country, with 10,000 apiece in Moscow and St. Petersburg alone. The bulk of the attendees were teens and people aged in their early 20s.

Authorities said the rallies were not authorized in many cities, including Moscow. The protesters, citing their constitutional rights and led by Navalny, marched anyway.

Riot police intervened in several cities, most notably in Moscow, where witnesses and media crews documented a brutal crackdown on what was largely a peaceful protest.

Officers used tear gas and physically beat protesters, including women and younger teenagers.

Pictures also showed some of the demonstrators being dragged away across asphalt.

2. What is Medvedev accused of doing?

Navalny's report alleged the Russian prime minister controls vast estates in Russia, as well as other assets including two yachts and vineyards in the Italian region of Tuscany.

Navalny claimed the assets were gifts from Russian oligarchs provided through charities established to funnel them to Medvedev.

Medvedev's spokesperson has denied all allegations and there has been no criminal investigation.

On the day of the protests, Medvedev wrote on Instagram that he "did some skiing" in an undisclosed location.

Meanwhile, most Russian households continue to be hit by the country's worst recession in two decades.

3. So who is Alexei Navalny?

The 40-year-old has been Russia's most successful opposition politician of the past decade.

In a country accused of industrial levels of corruption among officials, Navalny has made a name for himself with a series of scathing investigations.

He is currently mounting a bid for the presidential elections in March 2018, though the government insists he is not allowed to run because he has been found guilty in several criminal cases, including embezzlement.

Navalny says these charges have been fabricated to deny him a slot on the ballot.

In 2013, after one of the embezzlement charges was brought, the White House said it was "deeply disappointed and concerned" by the "politically motivated" ruling.

"Navalny's harsh prison sentence is the latest example of a disturbing trend aimed at suppressing dissent in civil society in Russia," then-White House spokesman Jay Carney told a news briefing.

4. Haven't the Russians protested before?

Sunday was the largest demonstration in Russia in at least four years.

Hundreds of thousands of people took to the streets between 2011 and 2013 in protest at Putin's decision to run for a third term, as well as his victory that was plagued by allegations of fraud.

The Kremlin responded to these demonstrations by cracking down on opposition leaders and activists, dozens of whom were jailed.

One rally in May 2012 ended in massive clashes with police in Moscow, though fewer people were detained then than on Sunday.

5. Does this mean Russians are angry with Putin?

Polls say Russians have been enthusiastic about their president ever since he annexed Crimea from Ukraine in 2014, a move condemned by the U.S. and its allies.

But pollsters have long complained that many people refuse to speak to them — which means no one, not even the Kremlin, knows what many Russians really think about the government.

Russia certainly has a host of problems, including an economic downturn prompted in part by sanctions leveled after Crimea and the fall in global oil prices.

This has been keenly felt among the country's younger generation, Ekaterina Schulmann, a political scientist at Moscow’s RANEPA academy, told NBC News on Monday.

"Russia is universally seen as a country of poor people, but what matters is not so much income level as the dynamics," she said.

Before the latest downturn, she added, "people’s disposable real incomes have been steadily growing for the last 15 years. We’re not used to getting poorer when we were yesterday."

Schulmann said that "the web-savvy young are especially worried about the absence of career prospects and opportunities of social and political self-expression."

6. What is the Kremlin's next move?

The Russian government usually issues harsh dismissals of any political demands, but Sunday was different.

Presidential spokesman Dmitry Peskov didn't write off the protesters' claims, instead saying Monday that "the slogans, the proposals and criticism voiced will be taken into account."

This sea change may have something to do with next year's elections, and Putin needing the youth vote.

"You just don’t do a festival of repression ahead of the elections, when you need these votes," Schulmann said.

However, pressure is likely to be applied randomly to some of the protesters, according to experts.

Navalny’s office was raided by security services, and the head of his staff was charged with extremism.

The opposition leader was fined $350 and jailed for 15 days.

However, polls suggest that were Navalny to run against Putin, he would likely lose by a sizable margin.

7. What is the U.S. saying about the rallies?

The State Department denounced the crackdown in Moscow and demanded the release of the peaceful protesters, and the European Union has voiced similar calls.

Kremlin spokesman Peskov promptly rejected those demands Monday.

But America's verbal intervention will likely only harm the protest, allowing the Kremlin to paint the protesters as naïve kids incited by Washington, according to Nikolai Petrov, an expert on Russian politics with the prestigious Higher School of Economics in Moscow.

However, this does not solve the underlying problems that brought people to the streets.

"The protest on weekend showed that the people still care about politics and are finding ways to channel discontent," Petrov said. "The Kremlin's tactics of simply ignoring corruption scandals is not working anymore."