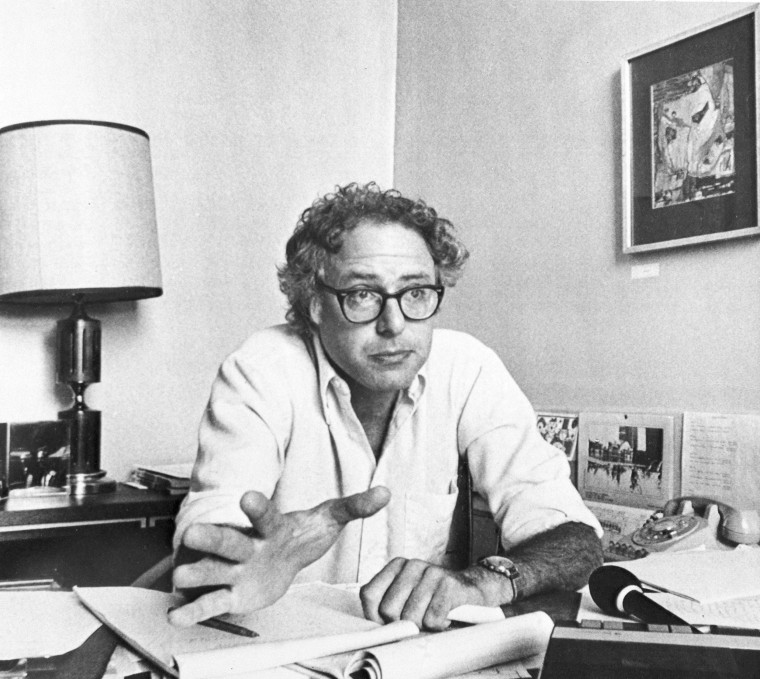

WASHINGTON — Bernie Sanders doesn't like to talk about Bernie Sanders, but that may be changing.

Sanders has chosen to launch his 2020 presidential campaign this weekend with a pair of rallies not in Iowa and New Hampshire, nor in his home state of Vermont, but in Brooklyn and Chicago — two places tied to a personal history that he rarely shares.

"Bernie dislikes the fluff, the focus on things that are not about policy," said Jonathan Tasini, a progressive activist who advised the Sanders campaign in 2016. "It's the reason people love him, too, because plenty of voters think we have a celebrity-focused, superficial political debate."

"But Bernie has evolved," Tasini continued. "As he is expanding his base, the bio helps people who aren't as familiar with him, to get the fuller measure of the man."

The kickoff in Sanders' native Brooklyn, his campaign says, will allow him to discuss how his working-class family's financial struggles informed his populist politics. In Chicago, he'll draw on his student activism in the civil rights movement and connect it to the fight today against President Donald Trump, whom he has dubbed a "racist."

Sanders prides himself on having espoused the same ideas for 40 years. But with everyone now copying those ideas, he has to sell himself, too. And his second presidential attempt offers him a chance to round out his public image.

For most politicians, "bio" is as interwoven into their message as a fictional superhero's origin story is with their powers.

But that's never been true for Sanders, so it's notable that he’s mining his past as he introduces himself to America.

Here's some of what Sanders 2.0 likely plans to talk about on the 2020 campaign trail: He was raised in a Jewish neighborhood in 1940s Brooklyn, where kids played stickball in the street and Nazi concentration camp tattoos peeked out from under sleeves in the grocery store.

His mother dreamed of moving the family out of their rent-controlled apartment, but his father never made enough money, giving Sanders an early introduction to class and the stress of financial struggles.

"There were arguments and more arguments between my parents. Painful arguments. Bitter arguments. Arguments that seared through a little boy's brain, never to be forgotten," he wrote in his memoir, "Our Revolution," published shortly after the 2016 campaign.

Sanders went to college in Chicago under Mayor Richard Daley, where he became politically radicalized in the tumult of the 1960s. He was arrested protesting housing discrimination, took a bus to Washington to see Martin Luther King Jr.'s "I have a Dream Speech," and was proud to be labeled an "outside agitator" by the cops.

"I learned to look at politics in a new way," he wrote.

Both are politically rich veins, especially his civil rights work, as Sanders tries to improve his standing among African-Americans. But advisers have struggled to get him to emphasize either in the past.

He'd be the first Jewish president in American history, but, like other parts of his personal life, he almost never discusses that part of his heritage, except when asked directly.

During his first campaign, he declined to join Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump in speaking to AIPAC, the pro-Israel group, and spent Rosh Hashanah 2015 addressing Liberty University, a global hub of evangelical Christianity.

"I'm very proud of being Jewish and that is an essential part of who I am as a human being," he said during a debate with Clinton, one of the few times his background came up in 2016. But he spoke in more political terms than personal, mentioning his Polish relatives' extermination in the Holocaust to say, “I know about what crazy and radical and extremist politics mean."

Harry Jaffe, a journalist who got his start in Vermont and served as press secretary for Vermont's other senator, the Democrat Patrick Leahy, attempted to trace Sanders' personal life for his 2015 book, "Why Bernie Sanders Matters." Sanders declined to participate.

"He doesn't really want to be explored. It's as if he left it behind and doesn't want to revisit it," Jaffe said. "He's about doing things that will right wrongs at the highest levels, and he doesn't see himself as being that personally important in the process."

And there are parts of Sanders' past that he would probably rather stay unexamined, such as the period in his life between college and his political rise when he wrote controversial essays, including one about women having rape fantasies.

"The oddest part of his life, which he will have a very hard time explaining, is the years that he was a basically a hippie knocking around Vermont," Jaffe said.

After graduating from the University of Chicago, he married a classmate and traveled with her to Europe and Israel, where they worked on a kibbutz.

Inspired by his childhood summers at Boy Scout camp and with some money from his recently deceased father, they bought a large plot of woodland in Vermont and lived in a converted maple sugar shack with no running water or electricity and only a cold stream to bathe in.

A few years later, he was divorced and living with a different woman who would become the mother of his son, Levi, who ran for Congress in New Hampshire last year.

He can bristle when asked about personal matters, which he often dismisses as "gossip."

"What are you, my psychiatrist?" he's quipped to at least one reporter.

Even his most devoted followers have learned relatively little about the man behind the rhetoric by listening to his speeches or watching his ads.

"He doesn’t like to talk about himself — or hear about himself," his wife, Jane, explained to a People magazine reporter who visited the couple in their home for one of the only soft-focus feature stories they participated in during the 2016 campaign.

When the buzzer went off on the dryer in the basement, Sanders took the excuse to leave the room and tend to the laundry. "That's my cue!" he said.

Sen. Jim Inhofe, R-Okla., has called Sanders one of his closest friends in the Senate. But he admitted a few years ago that after 25 years: "I, to this day, don’t even know if he has grandkids. Or even a wife."

"I don't think he has any other interests," Inhofe told Bloomberg Businessweek. "I've never heard him talk about anything besides something legislative."

That single-minded devotion to the cause is part of what has attracted so many followers to Sanders.

Asked to comment for this article about Sanders' more personal approach to campaigning, his spokesman Josh Orton said, "Bernie Sanders' family upbringing made him who he is today."

Sanders got away without talking about himself in 2016 in part because he was running against a candidate in Clinton whose personal history always overshadowed her ideas.

While her slogan was "I'm with her," he adopted one that was equally apt: "Not me. Us."

But whether Sanders likes it or not, presidential politics have been personal since at least the advent of television, where a sweaty debate performance can break one candidate, while an inspiring personal story can make another.

And while Sanders' biography is hardly conventional, neither are his politics.

"I started way, way outside of establishment politics," he wrote in his memoir.

In 2020, he hopes to finish in the White House.