The gerrymandering wars are heading South.

A number of Southern states, including Texas, Florida, Georgia and North Carolina, are prime targets for partisan gerrymandering as the congressional redistricting process gets underway after next year's statehouse elections, experts said.

"Many of the states that had the really aggressive gerrymanders the last time — Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin — the processes are much fairer there" now, said Michael Li, a redistricting expert at the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University, referring to what took place after the 2010 census. "The real worry is these fast-growing states in the South."

America's decennial congressional redistricting process — when roughly even-sized House districts are drawn, usually by state politicians — has become one of the most important battles in politics, as the parties seek to gain advantage by drawing sometimes crazy looking maps.

Activists say these partisan maneuvers undermine democracy and that politicians shouldn't be choosing their voters; politicians who gerrymander like to say that by winning elections, they've earned the right to draw the districts as they see fit.

The Supreme Court has declined to outlaw partisan gerrymandering — saying only states can police that — but it also removed a key safeguard against the practice by gutting the Voting Rights Act in 2013. That ruling means states with a history of racial discrimination, including Texas, Florida and North Carolina, no longer have to clear their redistricting maps with the Department of Justice before putting them in place.

That ruling, along with the growing populations, changing demographics and mostly single-party control, sets up Southern states as the most likely territory for partisan gerrymandering, experts said.

The South is "ground zero for this fight," said Dan Vicuña, a redistricting expert at Common Cause.

Vicuña said the Supreme Court's decision has put in place a "new legal playing field" for partisan gerrymandering and lawmakers can be expected to try to take advantage of that when they are drawing the House maps.

"You'll see kind of more blatant partisanship," he told NBC News.

Gerrymandering is so exacting and effective that state lawmakers, who often function as the map drawers, can hand control of Congress to one party for a decade. Republicans dominated the process last time, in 2010, and Democrats were forced to spend the next decade fighting gerrymandered maps in courts and losing elections in partisan-leaning districts.

Now, operatives in both parties are readying for an unprecedented fight in 2020 to elect those who will be the mapmakers in state legislative races across the country.

Former Attorney General Eric Holder and his group, the National Democratic Redistricting Commission, are leading the battle for Democrats. The group and its affiliates recently announced they had raised $52 million since 2017. They're targeting state legislative races in a dozen states, with more than half below the Mason-Dixon line.

"I'm bound and determined to make sure that candidates, activists and voters understand the stakes of the redistricting battle and the long-term consequences for our democracy," Holder said in a statement.

On the other side, the Republican State Leadership Committee is readying a defensive operation known as Right Lines 2020 to try and maintain the GOP's successes in 2010, sending out former House Speakers Paul Ryan, John Boehner and Newt Gingrich to raise money and keep the party focused on redistricting.

The Republicans are targeting races in 14 states, with six in the South. They declined to put a dollar number on the effort, but have said they are "planning multimillion-dollar investments in key states."

"We can't just assume that the success we've enjoyed in the states is going to be there," RSLC President Austin Chambers said, adding that he is concerned Republicans are more focused on re-electing President Donald Trump than the fight for statehouses that's so crucial to redistricting. "We're going to have to fight like hell to keep it — this is as serious as a heart attack."

While each state's process is different, there are three key Southern battlegrounds next year, experts and party officials said:

- Texas: It's expected to gain three congressional seats after the 2020 census and an intense battle over the partisan makeup of those new districts is expected. Democrats believe they have a shot at winning the nine additional seats in the Texas House of Representatives next year to take control of the chamber, after picking up 12 seats in 2018.

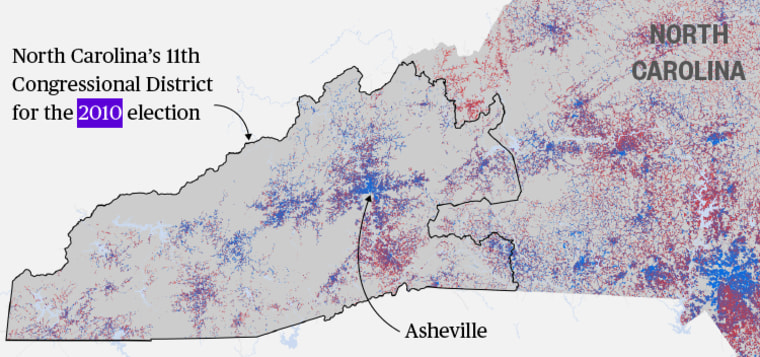

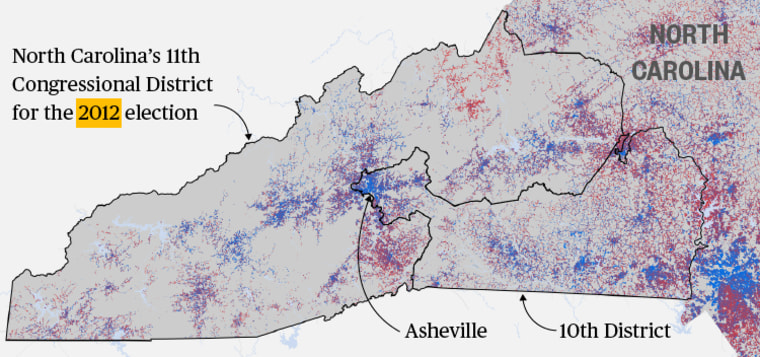

- North Carolina: State courts have made big efforts to curb partisan gerrymandering there — there have been more attempts at it than in any other state — but state lawmakers still have a lot of power. With population growth expected to add another congressional seat, both parties will be fighting for control of the state Legislature, which is currently run by the GOP. Democrats would need at least four more seats in the state Senate and six more in the state House to take full control.

- Florida: The state is anticipated to get two new congressional seats after the 2020 census, and Democrats are trying to flip both the state House and the state Senate. It's a tall order: Republicans have a 26-seat advantage in the House and a six-seat edge in the Senate.

Legislatures in other Southern states, including Georgia and Louisiana, also are in play.

Virginia poses a key test for national Democrats, who like Holder typically say they want fair — not gerrymandered — districts. Democrats have control in the state Legislature and the governor's mansion. If they wanted to gerrymander next year, they'll likely have the power.

"When Democrats are out of power, they say all the right things about gerrymandering," Li said. "But Virginia is a state with a lot of congressional districts and whether Democrats walk the walk when they have power — Virginia's going to be a big test of that. It’s a big test for Eric Holder."

John Bisognano, executive director of Holder's redistricting group, said Holder has spoken out against Democrats seeking to rig the system and the former AG also has expressed support for nonpartisan redistricting, a concept that's grown in popularity as states seek to opt out of the gerrymandering wars.

In the last decade, Colorado, Michigan, Missouri, New York, Ohio and Utah implemented changes to their congressional redistricting processes, with some states authorizing bipartisan commissions with the work in an effort to reduce the role of state lawmakers. For example, Missouri will ask a nonpartisan demographer to draw district lines, subject to approval by a commission made up of both Republicans and Democrats.

Still, not all commissions are created equally. In Ohio, voters passed a referendum last year requiring bipartisan support for redistricting plans in an attempt to prevent one party from forcing their House maps on the other. If the parties can't reach agreement, a bipartisan commission would draw the districts, but both Democrats and Republicans are angling for power on that commission and partisans can still push through four-year maps without minority party support.

"We supported an independent commission — well, we supported a commission," Bisognano said. "It's a commission of politicians."

Given that, both parties say the Ohio Statehouse is a top target in 2020.

CORRECTION (Dec. 29, 2019, 11:24 a.m. ET): A previous version of this article misstated the number of seats Democrats in North Carolina need to gain to take control of the legislature. It is at least four in the state Senate and six in the House; not eight in the Senate and 11 in the House.