LAS VEGAS — Hadeid Arreola sat at her family’s kitchen table during dinner about a month ago discussing the upcoming election with her parents and three sisters. Voting was important to her family, especially her parents, Mexican immigrants who became U.S. citizens about 25 years ago. They had always stressed its importance to their children.

But that evening, instead of talking about who they would vote for, they were debating how they would cast their ballots.

During a special session in August, amid Covid-19 safety concerns, Nevada lawmakers passed a bill that for the first time gave all voters the choice between voting by mail and going to the polls if the state is under a declaration of disaster or emergency.

Arreola’s mother and father, both in their 50s, worried about voting in person; the Latino community in Nevada has been hit hard by Covid-19, and her parents are avoiding crowds. But her older sister wanted to go to the polls; casting her ballot electronically reassured her that her vote would count.

“For me, I’m just still not sure what I’m going to do,” Arreola, 31, said. She works at Mi Familia Vota, a national, nonpartisan Latino voting group, helping people fill out their voter registration forms correctly. “I want to know for sure that my vote goes through, but I also don’t want to put myself at risk with Covid-19.”

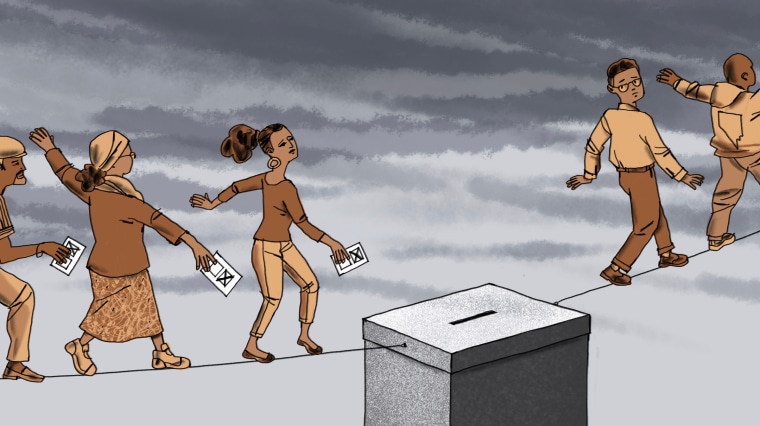

It’s a dilemma that many Latinos in the state are facing at a moment when Nevada voter advocacy groups are ramping up education campaigns in the Latino community to dispel myths about voting options and ensure that any confusion does not decrease turnout.

Latinos are a key demographic in Nevada whose turnout could swing the state left or right, voter advocates and political scientists say. Hillary Clinton carried Nevada by just 2 percentage points in 2016, and aside from former President Barack Obama’s 12-point margin of victory in 2008, no recent presidential candidate has won Nevada with a margin of more than 10 percentage points.

“If anyone wants to win this election in Nevada, whether it is the presidential or local, if you don't have Latino voters, you’re not going to close the deal,” said Cecia Alvarado, Nevada state director for Mi Familia Vota. “So we need to make sure that everyone has the right information because it’s important for the Latino voice to be heard.”

Latinos make up nearly 30 percent of Nevada’s population and almost 20 percent of eligible voters. Some of the first wave of Latino voters in the state came from Cuba to work in the gaming industry after Fidel Castro shut down gaming in 1959, and they tended to cast their votes for conservatives, said David Damore, a political science professor at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. But with the arrival of immigrants from countries such as Mexico and El Salvador, as well as a new wave of young voters born in the United States, the Latino vote has shifted to the left.

“The bigger the Latino vote is, the better the Democrats are going to do here,” Damore said. “If it's a small Latino turnout, that's going to tend to favor the Republicans.”

Under Nevada’s new law — which President Donald Trump's campaign unsuccessfully challenged in federal court — all active registered voters will automatically receive an absentee ballot by Oct. 17 whether they requested one or not. Nevada is one of nine states, along with Washington, D.C., that is mailing ballots directly to all voters.

For more of NBC News' in-depth reporting, download the NBC News app

It’s unclear how the new law could affect Latino voter turnout in Nevada. The state’s primary in June, which was held almost entirely through mail-in ballots, became one of the highest-turnout primaries in state history, with 491,654 votes cast, nearly 30 percent of all registered voters.

Still, more than 10,000 of those ballots were not counted, largely because they were submitted with missing or mismatched signatures, according to the Nevada Independent. Voter advocacy groups and civic organizations say this has contributed to voters’ concerns that they may make mistakes on a mail-in ballot that could discount their vote.

Advocates say they have been fielding scores of phone calls from voters ranging from how to send in their ballots to what signature they are supposed to use (the new law requires the signature on the ballot return envelope match the signature on file from voter registration).

“A lot of people feel like there is a certainty with seeing their vote go through electronically, and they are afraid they won’t be able to go back and correct a mistake like they can when using a voting machine or get help from a poll worker if they don’t understand something on the ballot,” said Rudy Zamora, program director of Chispa Nevada, a of League of Conservation Voters group that helps Latinos engage in the political process.

He added that the organization has also received questions about social distancing measures at the polls and whether early voting in person is safer. “We are spending a lot of time trying to help people figure out what option is best for them,” he said.

Lorenzo Becerra, 23, said he considered voting in person. But over the summer, he lost his great-uncle and great-aunt to Covid-19, and he worries about the impact of thousands of people gathering to vote.

“I don’t want to be a part of a bigger problem by going out to the polls,” said Becerra, a nursing student who also works for his family’s trucking business.

Still, he is nervous about making a mistake. He’s enlisted a friend who volunteers with a local civic organization to help him fill out his ballot properly once he receives it.

“It’s a really important election and I don’t want to do anything wrong and get my ballot sent back or not counted,” Becerra said. “I just want to get it right the first time.”

Some voters are concerned that the U.S. Postal Service will not get their ballots to the election office in time. Sol Del Risco, 18, a University of Nevada, Las Vegas, freshman and first-time voter, said she’s noticed delays in mail delivery lately, so she plans to bring her ballot to a drop-off site rather than put it in a mailbox.

“That seems like the best way to make sure it gets there,” she said.

Elica Arreola, 33, Hadeid Arreola’s sister, who works as a pre-kindergarten teacher’s assistant, said she was initially worried about mailing her ballot, but after learning that Nevada is enabling voters to track their ballots, she said she is leaning toward voting by mail.

Hadeid Arreola is still unsure. She’s going to keep an eye on how crowded the polls get during early voting. If they are not too bad, she may vote in person. If there are too many people, she’ll cast her ballot by mail.

She recalled voting in her first presidential election in 2008, when she went with her parents and older sister to vote for Obama. They were living in Idaho at the time and drove to the polls together. She remembered her father describing the choices they were going to make, reminding them that they could not work toward government solutions if they did not participate in the process.

“I’m going to vote no matter what,” Hadeid Arreola said. “I want my voice to be heard.”