WASHINGTON — In 2009, a newly-elected President Barack Obama called on lawmakers to remove limits on charter schools, saying it “isn't good for our children, our economy, or our country” to hinder their growth.

Ten years later, Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., announced an almost mirror-image position: A national moratorium on federal funding for charter schools pending an audit, and a ban on for-profit charter schools.

"Charter schools are led by unaccountable, private bodies, and their growth has drained funding from the public school system," his campaign said in a press release.

He's hardly alone. At an education event in Iowa on Saturday, in South Bend, Indiana, Mayor Pete Buttigieg sounded a skeptical note about charter schools.

"For-profit charter schools should not be part of our vision for the future," he told reporters. "And I think the expansion of charter schools in general is something that we need to really draw back on until we've corrected what needs to be corrected in terms of underfunded public education."

Charter schools — a type of public school that is independently operated and whose staff is often non-unionized — have long been a divisive issue within Democratic circles. Now, they're increasingly falling out of favor with the party's current crop of presidential candidates, who are aggressively courting teachers unions in a crowded field, and embracing education proposals more in tune with their demands.

Several candidates, including former Vice President Joe Biden and Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., have also criticized for-profit charters, a narrower status that the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools claims applies to only 12 percent of schools. The dominant stance in the field, however, has been indifference.

“In a few cases, they’re very clear, but in many cases it appears to us as though people have been doing a good job of dodging the issues, and that issue in particular,” said Carol Burris, executive director of Network For Public Education, an advocacy group that opposes the proliferation of charter schools and is tracking 2020 candidate positions.

Supporters and opponents of charter schools alike point to a long list of potential reasons for the shift among national Democrats away from Obama’s position.

State education cuts produced a backlash among voters that made funding for public schools and colleges more urgent priorities. Teacher strikes and related activism built sympathy for union complaints about low pay and lack of resources. In some places, parents rebelled against new testing and standards while high-profile scandals raised questions about oversight at various charter schools and helped critics build their case.

Then there’s one factor specific to the current White House: Education Secretary Betsy DeVos, a billionaire philanthropist and prominent supporter of alternatives to traditional public schools, who has become a hero to many on the right and a leading villain on the left.

“What DeVos does is crystallize all this,” Randi Weingarten, president of the American Federation of Teachers, said. “She is the epitome of the anti-public education oligarchs in this country.”

It's a stark change from the Obama years, when the president and his allies emphasized charter schools as a way to test and spread innovative new teaching methods. Allies in the education reform movement argued school systems should hold teachers and administrators more accountable for student performance by offering merit pay and closing down failing schools.

That stance often put Obama at odds with teachers unions, who argued that charter schools diverted resources from traditional public schools. The National Education Association, one of the biggest unions, even called on then-Education Secretary Arne Duncan to resign at one point.

“The corporate Democrats, led by people like Arne Duncan and Cory Booker and others with a lot of hedge-fund money behind them, had the view, basically, that teachers were stupid,” Weingarten told NBC News, discussing the era.

But, she said, there’s since been “a shift in the way teachers are viewed.” Instead of talking about how to get educators to shape up, Democrats tend to treat student and staff concerns as more closely aligned.

In recent weeks, candidates have rolled out pricey proposals to boost teacher pay and public school funding and expand access to higher education. Sen. Kamala Harris,D-Calif., released a plan to raise teacher pay by an average of $13,500. Many candidates have adopted debt-free or tuition-free college proposals and support universal preschool. Warren proposed canceling up to $50,000 in student debt per person. Biden has called for tripling Title I funding, which goes to schools with more poor students.

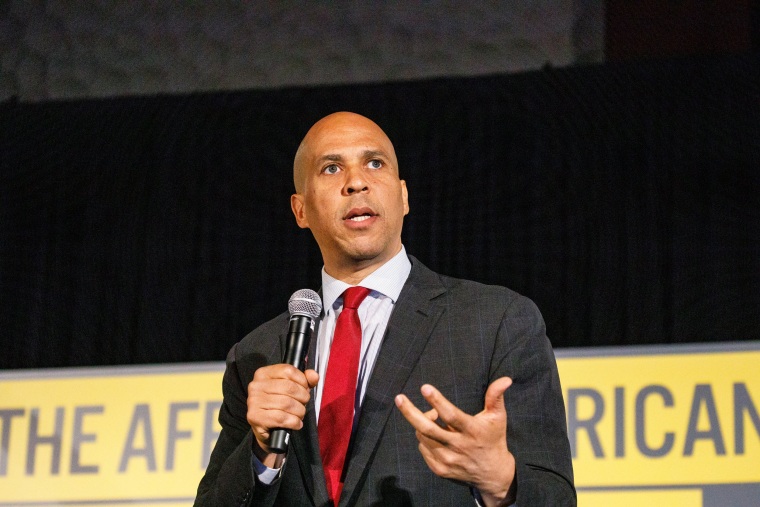

As Weingarten alluded to, Sen. Cory Booker, D-N.J., was one of the most prominent charter school advocates in the country as mayor of Newark, where he oversaw an overhaul of the city’s education system in tandem with Republican Gov. Chris Christie and high-profile philanthropists like Mark Zuckerberg. Newark's government did not have local control over its public school system when he took office.

As a presidential candidate, Booker has defended his record and some studies suggest student performance improved in the city’s charter schools.

“Cory supports high-quality public schools, including high-performing nonprofit public charter schools where local communities have determined these schools provide their children access to a great public education," Sabrina Singh, national press secretary for Booker's campaign, said in a statement.

Some observers on both sides of the debate believe he’s tried to mend fences with teachers unions as well. In his announcement speech, he pledged “to run the boldest pro-public school teacher campaign there is, which is how I ran the city of Newark” and he said in Iowa that he disagreed with some states’ handling of charter schools.

“Cory has been a champion for public school teachers, and his record proves that," Singh said.

Several presidential candidates — including Booker — voiced their support for a teacher strike in Los Angeles this year in which one of the union’s demands was a moratorium on charter schools. Booker is also running on a bill he sponsored, the STRIVE Act, which would fund teacher preparation and expand loan forgiveness programs.

“I think he’s changing,” Weingarten said of Booker. “Everybody evolves, I want to give him the opportunity.”

If Democrats are starting to return to their partisan corner on education with the other side in power, there would be recent precedent. After the Obama administration encouraged states to adopt Common Core education standards, Republican leaders who had previously supported the same approach faced a tea party backlash as conservative critics tied the policy to the president.

Today, not only the Trump administration, but also many of the prominent business leaders from the technology and finance world who back the charter school movement are on the outs with progressive activists. That makes the cause a harder sell to rank-and-file Democrats.

“I think the polarization we see in our politics writ large has come to the education issue,” said Michael Petrilli, a charter school advocate and president of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute. “I think that’s bad news for those of us who care about improving our education system.”

Many supporters of charter schools also say they see a racial component at play. Charter schools often serve low-income minority students in cities, and advocates point to research at Stanford University suggesting that urban charter schools have improved their performance. Since affluent white voters — especially in suburbs with high-performing public schools — are less likely to have direct experience with charter schools, they argue, they may be more likely to shift opinions based on the national political winds.

An annual survey by the journal Education Next in 2018 found support for charter schools had remained mostly consistent since 2016 among black and Hispanic Democrats, with 47 percent of each group supporting the concept, but plummeted among white Democrats, with 50 percent opposed, up from 37 percent two years earlier.

“Bernie Sanders apparently thinks he, in Vermont, knows better than low-income African American and Hispanic families in their cities about what’s best for their children,” Shavar Jeffries, president of Democrats for Education Reform and a former candidate for mayor of Newark, said.

Jeffries suggested DeVos’ unpopularity may have alienated some white suburban Democrats, but he bristled at the suggestion that the Trump administration had anything to do with his group’s work. He opposes for-profit charter schools, which were especially prominent in DeVos’ native Michigan, and supports proposals by 2020 Democrats to increase teacher pay.

How race plays into the debate is a complicated question. The NAACP called for a moratorium on charter schools in 2016 until they adopted stricter oversight and transparency standards, and some critics have accused individual charter schools of structuring themselves to exclude low-income minorities. Sanders, in his own call for a freeze, accused charter schools of encouraging segregation.

But proponents say the segregation charge is especially off base, since many charter schools were deliberately created to expand students' choices in cities where public schools had long been effectively segregated. Last month, three local NAACP chapters in California also announced their opposition to the national group’s moratorium.

While the headwinds are strong right now for groups like DFER — the Colorado Democratic Party even passed a resolution last year calling on their state chapter to drop “Democrats” from their name — Jeffries said the movement was used to intra-party scrapping.

“We’ve been in these fights for 20 years,” he said. “We expect to be in them for another 20.”

Priscilla Thompson reported from Des Moines, Iowa, and Benjy Sarlin from Washington.