WASHINGTON — Maybe the Build Back Better Act was destined to fail.

Maybe the White House and Democratic leaders misplayed what could have been a winning hand, even if it had no margin for error, and jeopardized the centerpiece of their agenda.

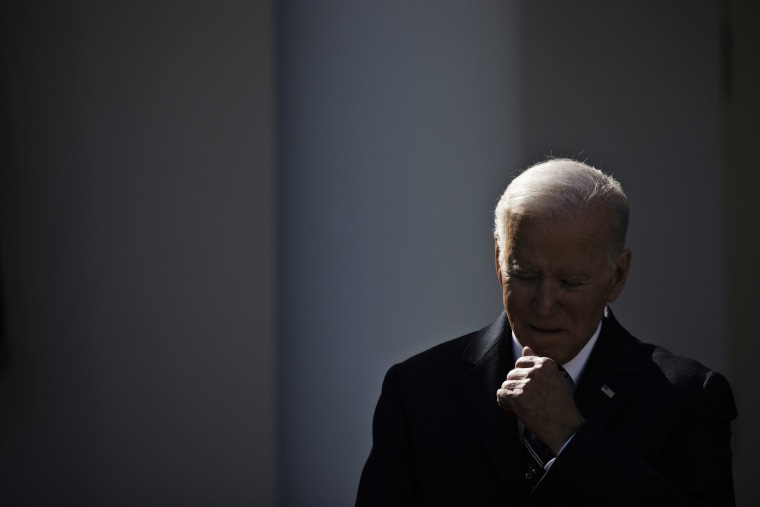

Or perhaps rank-and-file Democrats, coupled with unanimous Republican opposition, gummed up the deal-making process in a way that Joe Biden the candidate said he was uniquely suited to surmount, but in practice as president could not.

In conversations with more than a dozen people involved with the legislation, conflicting theories emerged about who is responsible for President Joe Biden’s lost legislative agenda. The enduring tension looms over quiet discussions between the White House and congressional Democrats on a dramatically scaled-back bill, with finger-pointing about who’s to blame for the failure of the larger bill amid uncertainty about what, if anything, might actually pass ahead of November’s midterm elections.

The White House blames it on the difficulties of uniting the slimmest of Democratic majorities, including a 50-50 Senate, and media framing of the initial legislation. Moderate Democrats blame progressives for fueling unrealistic expectations. Progressives blame moderates for working against Biden. Some blame Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer or Sen. Joe Manchin of West Virginia. Other Democrats say leaders made a tactical error by splitting off the infrastructure bill.

And still others fault Biden and his team, saying they erred in branding Build Back Better as a big, bold, once-in-a-generation — read: expensive — piece of legislation and by trying to, as one Democrat put it, “placate everybody.”

Another Democrat placed fault with the current polarized political climate, saying: “It’s the process.”

John LaBombard, the former communications director for centrist Sen. Kyrsten Sinema, D-Ariz., said part of the problem was a mismatch between “sky high” expectations and narrow margins. Democrats’ thin majorities in the House and Senate necessitated the votes of moderates who “did not campaign on big, bold, radical, progressive change,” he said, citing Sinema, Manchin and Rep. Stephanie Murphy of Florida.

“They’re not going to be rolled,” LaBombard said. “When we raise expectations and fail to meet them, we leave our supporters disenchanted and disappointed.”

Some Democrats, including in the administration, conceded early on that the initial $3.5 trillion Build Back Better Act was less a realistic legislative endgame and more a blueprint of the president’s priorities — a mixture of his campaign pledges and measures aimed at drawing a contrast with Republicans. It was a starting point for negotiations, they say.

But that’s not how it was sold to the public.

LaBombard, who left Sinema’s office in February to become senior vice president at the public affairs firm ROKK Solutions, said the decision to “focus on how many trillions of dollars of taxpayers’ money is going into a bill” that needed to pass on a party-line basis was not “a strategy designed to earn support from our caucus’s moderates,” even if it had “meritorious and important policies.”

After months of negotiating, the legislation was trimmed to about $2 trillion to meet the demands of centrists in both chambers and passed the House in November. Then it came to a screeching halt in December when Manchin announced his opposition to the bill.

There is now a quiet effort underway to pass some version of the president’s agenda under a legislative process known as reconciliation, which allows Democrats to circumvent Republican opposition and pass a bill along party lines. Officials said Steve Ricchetti, counselor to the president, and Louisa Terrell, the White House director of the Office of Legislative Affairs, are having conversations with Democrats on Capitol Hill. That effort, however, has hardly been central for Congress so far this year, as the focus has been on Russia’s war in Ukraine, funding the government and confirming a Supreme Court nominee.

Democrats also expect to pass the CHIPS Act, to bolster the domestic production of computer circuitry, and an election security measure in coming weeks. And officials are quick to argue that even without Build Back Better, the president’s legislative accomplishments are significant — from $1.9 trillion in Covid relief to the $1 trillion infrastructure bill.

“The President’s focus is on the path forward: on following unprecedented job creation he’s delivered with an economic plan for the middle class that fights inflation for the long haul, cuts the cost of prescription drugs, child care, and energy while taking on the climate crisis, and further reducing the deficit,” White House spokesperson Andrew Bates said in a written statement.

The president’s defenders also push back on the notion that he and his top aides tried too hard to please everyone in the party, pointing out that he’d pressed upon Democrats that everyone was not going to get everything they wanted.

Apart from Manchin, the one individual that seems to get the most blame is Schumer.

A senior House Democratic aide pointed to Schumer’s decision last summer — amid negotiations on a $3.5 trillion bill — to spend months not sharing with the White House or Speaker Nancy Pelosi a letter from Manchin, dated July 28, in which he said he would not support a bill that cost more than $1.5 trillion.

“He knew where Manchin was and he didn’t say a damn thing,” the aide, clearly still frustrated, said of Schumer. “At the same time the House and Senate cut a stupid deal to come up with budget reconciliation at $3.5 trillion, when Chuck Schumer knew that wasn’t going to happen.”

The senior House Democratic aide also criticized the White House legislative affairs operation.

Asked for comment, a Schumer spokesman referred to the majority leader’s recent remarks to reporters that there are “ongoing discussions” with Manchin and others, and that reconciliation is still “a high priority” for Democrats.

Other people close to Schumer say he kept it secret because he was trying to change Manchin’s mind. Schumer allies note that Manchin’s views have shifted along the way and question whether he ultimately even wanted to support the package.

“It was always going to be a tough needle to thread in a 50-50 Senate,” said Matt House, a consultant and former communications director to Schumer. “It was made tougher by having the 50th vote seemingly uninterested in finding a path to voting yes.”

Biden tried to rebrand his Build Back Better agenda in his State of the Union address in hopes of one last shot at a bill. The White House’s hope was that the new approach would make Biden’s legislative goals clearer and less likely to turn off Americans who are wary of big, expensive bills. The president said his plan now focused on four things: lowering the cost of prescription drugs, energy and child care, and raising taxes on Americans making more than $400,000 a year.

But residual distrust and frustration on all sides hangs over the process. The White House was furious with Manchin when he backed out of negotiations in December, as were progressives who said it was exactly what they feared after Biden and Democratic leaders made the decision to break off physical infrastructure funding and pass it separately. (Moderates say they — and Biden — ran on working with Republicans and this was their opportunity.)

Indeed, despite the current attempt to salvage some of the president’s agenda, there is a recognition among Biden’s team that “their big legislative days are behind them,” another Democrat close to the White House said, given the window for passing legislation ahead of the midterms closes in just a few months and Republicans are expected to pick up seats in November.

Manchin has kept the door open to supporting a narrower bill that includes tax revenues, prescription drug savings and climate change funding. But he’s not the only Democrat the White House could struggle to get on board. And many Democrats say in retrospect the West Virginia senator’s $1.5 trillion legislative framework was far more sweeping than anything Biden might get now.

“If you look at the old Manchin deal, every progressive would love to have that back,” said one Democratic operative with prominent clients in the party.