Republican infighting in Washington may be grabbing headlines, but it’s outside the Beltway, in the trenches, that the party’s civil war is really being waged.

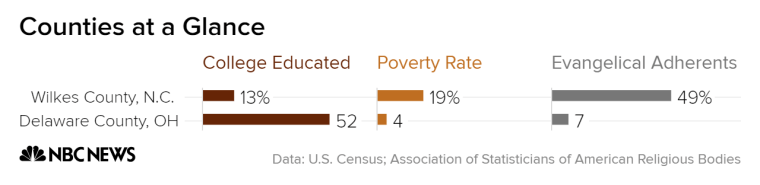

The battleground can be seen in the rural, rolling hills and evangelical congregations of Wilkes County, North Carolina, and the upscale suburban sprawl of Delaware County in Ohio.

For a generation, those communities — and scores like them — have been bound together by a Republican Party that served the interests of these diverse factions. But increasingly, there is widespread agreement on one thing: The GOP is changing, and nobody knows what it will look like when the dust settles.

On the struggling streets and in the crowded pews of Wilkesboro, N.C., voters sense that a conservative revolution has arrived, and Republicans here relish the thought of overthrowing the Washington establishment and remaking the party in their own faith-driven image.

Sitting in a local diner recently, James Jones, 59, who voted for and supports President Donald Trump, smiled at the possibilities. “I think Trump is busting up the GOP, and I am so glad. I love it," he said. "We need a real party. We might keep the name Republican, but we need change.”

Meanwhile, in wealthy exurban Columbus, Ohio, there is hope that Republicans will do what they always do, fall back in line for the good of the party, leaving plenty of room for the country club set that has long dominated its upper echelons.

Related: GOP Divide Goes Beyond Washington

But there is also uncertainty. Jai Chabria, who once worked for Gov. John Kasich, a Trump critic and Republican establishment favorite, sees changes ahead. “I don’t think I can sit here and tell you what it is going to look like in 10 years, but it’s going to look radically different that it did before,” he said.

These clashing visions of what the party is, and what it will become, are at the root of the GOP’s challenges in the months and years ahead. As the Republican Party sorts out its identity in the age of Trump, the road ahead seems destined for major intra-party conflict.

Wilkes County, God and Politics

Last November, Donald Trump didn’t just win Wilkes County, he owned it, capturing 76 percent of the vote. On the surface, it’s an odd fit — the brash New York billionaire with his coarse and caustic talk, and a quiet, serene community where roughly 50 percent of the population subscribes to a form of evangelical Christianity.

But that misses a larger point according to Pastor Ken Pardue, 74, of Antioch Baptist Church.

“First, do I believe that he is a spiritual man? Absolutely not," Pardue said of Trump. "But do I believe he is a friend to Christianity? I absolutely do."

"The second thing is, he loves America," he continued. "The people who were born here love America. They remember a different America, and he’s promising to bring that America back.”

Wilkes has experienced its share of economic trouble. Furniture manufacturing, once an economic driver, has dried up. And Lowe's, the national home improvement chain born in Wilkesboro, the county seat, is gone after the company’s top executives pulled up stakes and moved an hour south to Mooresville in 2005, closer to Charlotte.

At Cagney’s Kitchen in Wilkesboro, Mary Shew, 77, suggested that Trump is the last hope for an America in decline. “I think the powers that be, the elite, the globalists, will do all they can to stop any move Trump makes as far as protecting the country and protecting the people, because they don’t want their little red wagon overturned.”

“I think the parties are two wings on the same corrupt bird, and it has to be corrected,” Shew said. “If it takes blowing up the party to get the country back in line, that’s nothing to me. It’s our country that matters to me.”

Daily life in Wilkesboro evokes a gentler time. The traffic moves slower. The local AM radio station has an on-air swap shop, a lost-and-found and a community calendar (“bring a covered dish”). The upscale chains that dominate urban communities are absent. There is no Starbucks here. No Chipotle's.

What it does have is houses of worship. There are roughly four dozen churches for 8,000 residents in Wilkesboro and neighboring North Wilkesboro. Churches for Methodists, Pentecostals and Baptists (who account for about half).

And that faith extends deeply into politics. Conversations about the state of the union often turn to the Book of Revelations and the word “globalism,” which has a meaning that extends far beyond trade and economics here. It’s perceived as a gateway to the rise of a one-world government that is a precursor to the coming of the End Times.

“When you say the word ‘global,’ Christians are automatically wary of it because of scripture,” said Pastor David Dyer, 33, of Fairplains Baptist Church. “The Book of Revelations speaks of things to come, and it says there is going to be this reassertion of global order. And you see that God is disapproving of man trying to conquer and rule over other man.”

For Dyer, the tipping point with Trump was his selection of Mike Pence for vice president, and that “rare choice’ suggested to him that Trump was a different kind of Republican taking the party in a new direction.

“People are no longer seeing Republican/Democrat or even conservative/liberal. What people like me are seeing is establishment/insurgent, establishment/newcomer,” said Dyer, who said he is registered as an independent. “People that have been in Washington too long are part of the problem, no matter what party they are from.”

Delaware County, the Establishment and Tradition

In Delaware County, Ohio, where party loyalty ranks high on the list of important values, the sentiment among Republicans couldn’t be more different. Trump also won here in November, but then Republican presidential nominees always win Delaware County. The last Democrat to win it was Woodrow Wilson in 1916.

But the county has had mixed feelings about Trump. The intra-party tensions became so heated during the 2016 campaign that the county Republican headquarters did not put Trump signs up in its window, instead consigning them, out of sight, to a back room. Those tensions persist one year later.

Mike Ringle, a 25 year-old recent college grad who jokes that he aspires to be a member of the GOP establishment, has concerns about what Trump means for the party in the long term. “What he’s doing is casting the Republican Party in a bad light. It’s divisive,” he said. “I want to be hopeful something good can come out of this presidency. I still am, but he has to change.”

If you imagine the home of establishment Republicans in your mind’s eye, it would probably look a lot like Delaware County. On the edge of Columbus, it is largely a collection of well-kept homes, golf courses, upscale retailers and coffee shops. Suburbs give way to rural areas and the quaint downtown of the city of Delaware, home to Ohio Wesleyan University.

The establishment also looks like Chabria, 40, the former Kasich aide. “I became a Republican because of Ronald Reagan, but that’s not what our party is anymore. Am I OK with that? It depends on what it looks like.”

As an example of what the party cannot look like, Chabria cites the white supremacist rally this past summer in Charlottesville, Virginia. He says he believes the parts of the party that embraced that event or refused to condemn it will eventually be drummed out of the GOP.

“There’s clearly a battle going on in the party right now, and it’s not just two sides — it’s multiple sides,” he said. “There’s a civil war, and the Republican Party is going to look like something different, OK? But there will still be a free-trade wing of the GOP. There will still be a Chamber of Commerce advocating for these things.”

In Delaware County, globalism is not a dirty word. In the world of the new economy, this is the home of the economic winners. Median household incomes are up. The population has grown, and the unemployment rate is below the national average.

James Franklin, a political science professor at Ohio Wesleyan, says the area's comfortable economic level has kept the populist anger stirring other parts of the GOP at bay.

“People here generally support levies for schools, public parks, libraries," Franklin said. "People are willing to use their tax dollars to support these things, and that speaks to a more moderate Main Street Republicanism."

Franklin points to the recent victory of Roy Moore, a controversial former state judge, in Alabama's GOP Senate primary over an establishment-backed incumbent as an inflection point for voters in Delaware County. “I think there’s a real question about the future of the politics here. If the party is moving more toward the Roy Moore corner, will the people here stay Republican?”

Trump has supporters here as well, of course.

Christopher Dobeck, secretary of the Ohio Wesleyan College Republicans, says he’s firmly behind the president and appreciates the changes he’s bringing to the party. “There are plenty of young Republicans in the world, and their views are different from their parents and their grandparents,” he said. Ideas like protectionism, which were once anathema to party regulars, are being more embraced by the young Republicans he speaks with.

All of this leaves the Delaware County Republican Party, long a voice of the GOP establishment, in a complicated position with the 2018 midterm elections approaching.

Off the record, people in the party here acknowledge that the mission next year is reuniting the party — not blowing it up but stitching it back together. Getting past the fights over lawn signs and “falling in line” behind the common good of the party — in short making 2018 not about Trump but about Republicans as a group.

That’s the plan anyway. The question is what happens if the establishment gets overrun, in Delaware and elsewhere?

“We have been overrun. That’s what happened,” said Chabria, who says he still isn’t sure if the GOP’s establishmentarians understand that there is a war underway within the party. “History is littered with things changing and evolving or completely disappearing."

"I think the party probably survives, but it evolves," he added. "And what does that look like? That’s what we’re talking about.”