In a nod to the importance of black voters to the Democratic Party, the South Carolina primary is designated as a crucial early test for the first time, and two black candidates step forward to run. But it’s one of their white opponents who wins a majority of the black vote, and the nomination.

After the Clinton-Gore years, the Democratic presidential nomination was truly wide open.

After Bill Clinton's unopposed renomination in 1996 and Al Gore's undefeated romp over a single opponent in 2000, the party was in need of a new leader to oppose George W. Bush. The national political atmosphere was charged. A country still traumatized by the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks found itself divided by the invasion and occupation of Iraq. Among Democrats, who still seethed over Bush's Supreme Court-assisted victory in 2000, the will to unseat the president was strong.

In theory, there was a clear opening for the first full-fledged black candidacy since Jesse Jackson's. The bond between black voters and the Democratic Party had only strengthened in the '90s, and a significant change to the calendar promised to expand their influence: South Carolina would hold its primary immediately after Iowa and New Hampshire. The move was initiated by the state's Democratic leaders, who'd watched with envy as their Republican counterparts gained enormous national clout through their "first in the South" GOP primary, which had started in 1980.

But there were no obvious black candidates. Jackson, whose stature had dimmed since his presidential runs and who'd taken a hit with the revelation that he'd fathered a child with an aide, was a nonstarter. There were also no sitting black governors or senators. This is what opened the door for the Rev. Al Sharpton, a preacher and New York-based activist, to try his hand at national politics. Sharpton began testing the waters early in the cycle, making a trip to Iowa in February 2002, and announced a year later that he would, in fact, run. "I will be attempting to expand the party to disaffected voters, minority voters and young voters, who will be the margin of victory in 2004," he said. (“Sharpton Takes Step in Presidential Bid,” The New York Times, Jan. 22, 2003.)

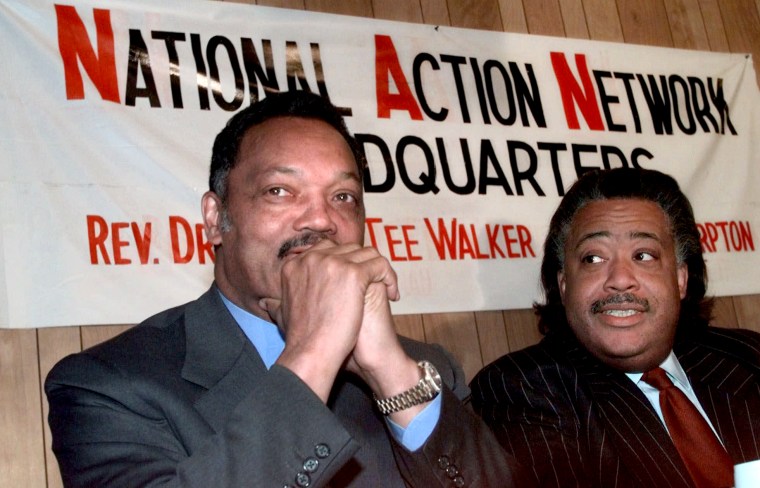

Sharpton, who currently hosts a show on MSNBC, called Jackson his "mentor" and "surrogate father," but there was clear tension between them. Jackson refused to endorse Sharpton, who in turn accused Jackson of becoming a weakened "establishment" figure during the Clinton years. Jackson, Sharpton said, went from being number two to Dukakis in 1988, to four years later at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago "begging to get a primetime speech, which he didn’t get. We can't tolerate that.” (“Sharpton tuning primary battle cry,” George Will, The Albany Times-Union, Jan. 10, 2002.)

One of the questions hanging over Sharpton's candidacy became whether he would emerge from it having eclipsed Jackson as the most prominent black political voice in the country.

In many ways, Sharpton was working off the old Jackson formula, aiming to attract wide black support and playing for leverage and influence. His campaign, though, faced more skepticism than Jackson's had, even among black leaders.

Sharpton had run for office three times in New York, attracting sizable black support but never making it out of a Democratic primary. And his name remained linked with a deeply polarizing episode that had served as his introduction to much of the country: his support for Tawana Brawley, a teenager whose claims that four white men had raped her became a national sensation before they were debunked.

There were also doubts about his seriousness, especially as he struggled to meet federal matching fund requirements.

One of the architects of Jackson's '84 and '88 campaigns, Ron Walters, urged black leaders to unite behind Sharpton. "We have to use leverage politics," he said. "If we don't, it dissipates our power." (“S. Carolina black voters eager for a say in race,” Gromer Jeffers Jr., The Dallas Morning News, Jan. 29, 2004.) But many disagreed. In New York, Sharpton's home base, the most prominent black leader, Rep. Charles Rangel, endorsed retired Gen. Wesley Clark. In South Carolina, Rep. Jim Clyburn went with Richard Gephardt, his House colleague from Missouri. Asked about his lack of support from top black leaders, Sharpton said, "Only people with bad credit need co-signers." (“That’s Al, Folks!”, Zev Chaffets, New York Daily News, Jan. 19, 2004.)

And a second black candidate emerged. Carol Moseley Braun had made history in 1992 when she became the first black woman elected to the Senate. She began her term with a high-profile skirmish in which she prevented the reauthorization of a patent for a Confederate symbol, but her political standing was ultimately weakened by a series of controversies that led to her re-election defeat in 1998. When she stepped forward to run for the Democratic presidential nomination, it caught practically everyone by surprise. And when she said she’d been encouraged by Donna Brazile, who’d been Al Gore's 2000 campaign manager, it spawned theories that she was being recruited by party leaders to divert black votes from Sharpton.

Braun was largely ignored by black leaders and raised only a few hundred thousand dollars. While she did nab endorsements from the National Organization for Women and the National Women’s Political Caucus, her campaign gained little media coverage. Nonetheless, her presence meant that, for the first time, a Democratic presidential race would feature two major black candidates. Would black voters side with one or the other, even if black leaders didn't?

Another question took on urgency as the campaign unfolded: Could Howard Dean, the governor of Vermont, make inroads with black voters?

His campaign had begun as an afterthought, but by the early days of 2004, he'd become an utterly unlikely front-runner, powered by his anti-war stance and backed by an emerging class of liberal bloggers. Dean had no previous experience courting black votes, though, and was seen as potentially vulnerable once the race moved on from Iowa and New Hampshire. His rise also rankled Sharpton, especially as Dean began reeling in endorsements from black leaders — including Rep. Jesse Jackson Jr., his estranged mentor’s son.

When the Jackson endorsement was announced, Sharpton released a statement: "Any so-called African-American leader that would endorse Dean despite his anti-black record is mortgaging the future of our struggle for civil rights and social justice, to back a candidate whose record on issues of critical importance to us is no better than that of George W. Bush.” (“Sharpton Calls Dean’s Agenda Anti-Black," Brian Faler, The Washington Post; Oct. 29, 2003.)

Dean stepped into controversy by arguing that he could beat Bush by, in part, being "the candidate for guys with Confederate flags in their pickup trucks." Sharpton tore into him, saying at a debate that Dean "sounded more like Stonewall Jackson than Jesse Jackson."

The first test ended up coming in majority black Washington, which scheduled its primary for mid-January, jumping ahead of Iowa and New Hampshire. The contest was nonbinding — no delegates at stake, just bragging rights — and was intended to highlight the issue of voting rights for the district. But the early date violated Democratic National Committee rules, and most of the candidates demanded that their names be removed from the ballot. Sharpton and Braun didn't, though, and neither did Dean, who refrained from active campaigning while hoping a strong showing would demonstrate appeal that crossed racial lines.

Dean did pull out a win, with 43 percent of the vote, but Sharpton wasn't far behind with 34 percent. There were no exit polls, but a precinct analysis suggested that Dean’s victory was keyed by massive margins in heavily white areas of Northwest D.C. and that he lagged far behind Sharpton in predominantly black neighborhoods (“D.C.’s White Voters, Not Black, Made Difference for Dean,” Craig Timberg, The Washington Post, Jan. 16, 2004.)

Braun, who gained just 12 percent in the D.C. primary, dropped out the next day and immediately endorsed Dean. The Democratic race then took an abrupt turn when, less than a week later, Dean finished a distant third in Iowa, losing to Sen. John Kerry of Massachusetts by a 2-to-1 margin. Months of momentum evaporated for Dean as Kerry rapidly gained support, following up his Iowa performance with a New Hampshire win. Dean pressed on, but his campaign was in free-fall.

A week later, South Carolina took its turn. With another win, Kerry would put essentially wrap up the nomination on the spot. He was boosted by a late endorsement from Clyburn, the state's top black political leader, after his first choice, Gephardt, dropped out. Kerry's closest competitor appeared to be Sen. John Edwards, a native South Carolinian. Sharpton, who'd barnstormed black churches across the state, was the wild card. "I'm not running for a job. I'm running for a cause!" he declared (“Presidency not prize Sharpton’s pursuing,” Shawn McCarthy, The Globe and Mail, March 1, 2004.)

When the votes were counted, Edwards finished on top, keeping his campaign on life support. Kerry was second and Sharpton, with 10 percent, a distant third. Black voters made up almost half of the electorate and narrowly favored Edwards over Kerry, 37 percent to 34 percent. Sharpton was the choice of 17 percent of black voters, according to NBC News’ black voter data analysis.

Sharpton claimed success, but the result made clear that he wasn't going to replicate the overwhelming black support Jackson achieved in his two bids. He stayed in the race for a few more weeks as his support among black voters ranged from 6 percent to 16 percent — except in New York, his home, where he won 34 percent among black voters. Meanwhile, besides the South Carolina hiccup, Kerry was posting one crushing victory after another. The Democratic establishment, black and white, closed ranks around him, and by the end of March the race was over.

"Black voters," The Washington Post wrote in the waning days of the campaign, "say they appreciate Sharpton's candidacy, but they have no interest in using their votes to make a statement — they want to oust Bush and they think Kerry is their best shot." (“Black Voters Align With Democrats Against Bush,” Vanessa Williams, The Washington Post, March 1, 2004.)

Sharpton's critics claimed that the campaign had weakened him, since he didn't come close to winning a single primary and trailed decisively among black voters. But he did achieve a different kind of breakthrough, stealing the show with punchy one-liners at debates and even hosting “Saturday Night Live” during the campaign.

"I don't think anyone denies that I have built a national personality," he said. (“Sharpton’s Next Role: Talk Radio? Reality TV?”, Jim Rutenberg, The New York Times, March 8, 2004.)