WASHINGTON — The entire political world is watching Alabama's Senate race, but what happens Tuesday is anybody's guess.

The highly unusual nature of the election, along with the difficulty faced by pollsters, has made the race murkier than a cypress swamp.

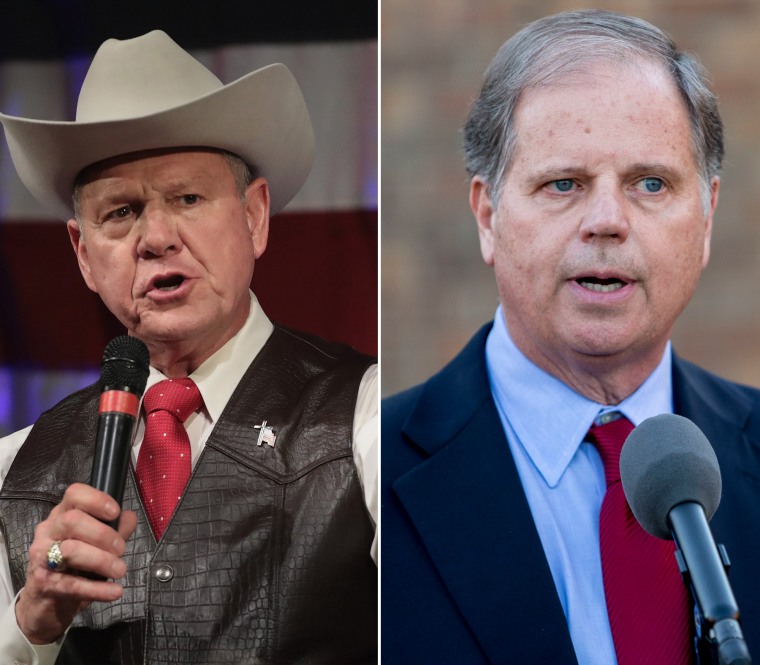

Recent polls show Republican Roy Moore leading Democrat Doug Jones by single digits, and most experts would bet on the Republican to prevail in the heavily red state — but they probably wouldn't wager much on it.

"There is no like election like this one," said Zac McCrary, a Democratic pollster based in Montgomery, whose firm, Anzalone Liszt Grove Research, has been involved in some of this year's biggest races.

Turnout is always tough to predict in a special election, especially one two weeks before Christmas. Even establishing a baseline of expectations for the race is slippery, since few have bothered polling a state where elections are generally predetermined for candidates with an "R" next to their name on the ballot.

The allegations of sexual impropriety against Moore may keep some Republicans home and could lead others to cast write-in votes, following the example of Sen. Richard Shelby, who said Sunday on CNN, "I couldn’t vote for Roy Moore." But the extent of those GOP defections is impossible to gauge.

Also confounding pollsters in Alabama is the degree to which President Donald Trump's election has disrupted the political environment in ways that are still not fully understood, but are clearly energizing Democrats in places they are usually dormant. And finally, add to the muddled mix Jones' heavy advantage on ad spending and get-out-the-vote operations. How much difference that will make on Election Day is another "X" factor.

PHOTOS: On the campaign trail with Roy Moore

Taken together, the only thing analysts and pollsters know for certain about the race is that they're uncertain about it.

David Byler, the chief elections analyst for the conservative Weekly Standard, said observers are "flying blind in Alabama," while the Washington Post's Philip Bump wrote that the cascade of complications make the race "all but impossible" to forecast.

Tom Bonier, the CEO of the data analytics firm Target Smart, said "nobody has any clue what turnout is going to look like," writing on Twitter that his overall assessment of the race is: ¯\_(ツ)_/¯. (That's a "shruggie" emoji, indicating a "who knows?" lack of knowledge about a particular topic at hand.)

Uncertainty about the contest even led one online polling firm, Survey Monkey, which regularly partners with NBC News, to take the highly unusual step of publishing the results of its latest poll on Saturday without making a prediction.

Instead, Survey Monkey offered estimates of 10 different potential outcomes, based on varying turnout scenarios.

"Data collected over the past week, with different models applied, show everything between an 8-percentage-point margin favoring Jones and a 9-percentage-point margin favoring Moore," Survey Monkey's Mark Blumenthal wrote. "(T)he findings make a projection of the outcome virtually impossible."

What few polls that do exist in Alabama generally come from lesser-known firms that don't use the more sophisticated — and expensive — techniques favored by experts. They rely on automated robocalls, which generally are prohibited from calling cell phones, and online surveys, which vary widely in quality.

Survey Monkey, while using online surveys, has developed a reputation as more credible than many competitors because of special models they employ.

Even under more favorable circumstances, polls of Senate races tend to be less reliable than those of presidential contests. An analysis by The Economist found an average error of 6 percentage points in Senate race polling from 1998 to 2014.

Just last month, pollsters missed the mark by a similar margin in Virginia's gubernatorial campaign, which was this year's only "normal" major competitive general election. Polls there were all over the place heading into Election Day, finally landing on a prediction, according to the Real Clear Politics average, that Democrat Ralph Northam would win by about 3 percentage points. He ended up winning by nearly 9.

A six-point polling error Tuesday would easily put Jones ahead of Moore, who trailed by 3.8 percent in the Real Clear Politics polling average of the most recent eight polls, as of Sunday. Averages help provide a better picture than individual polls.

Fewer than 500,000 Alabamians voted in the GOP runoff election in late September, when Moore beat Sen. Luther Strange. Turnout is expected to be higher in Tuesday’s election, but Alabama's Secretary of State is still only predicting turnout of about 25 percent of registered voters, well under 1 million.

Low turnout magnifies even small errors in pollsters' assumptions, along with marginal changes to the landscape, such as weather, since every individual vote carries more weight. By the same token, even a limited number of write-ins could tip the balance in a tight race.

And pollsters say there are few lessons to apply to Alabama from the handful of other elections this year, given the stark differences between those races.

For example, Georgia and South Carolina both held special congressional elections on the same day in June. But the outsize attention and money brought to bear in Georgia's contest led more than 250,000 voters to cast a ballot, while fewer than 90,000 did so in South Carolina, despite both districts having roughly the same population.

Then there's the fact that, given the questions around Moore, many Alabama Republicans may not yet know themselves what they’re going to do, or whether they're going to vote at all.

And there's even concern that some voters may be lying to pollsters about their intentions because they feel uncomfortable revealing their support for someone accused of sexual misconduct with teenagers. For that matter, there may also be "shy" Jones voters who don't want their conservative friends and family to know they're considering breaking ranks to vote for a Democrat.

Given the antipathy some Moore supporters feel for the media, which sponsors many public polls, it's possible some are refusing to accept pollsters' calls. At a Moore rally last week, several supporters declined interview requests because they said they didn't trust the press.

"There are so many wildcards here," said McCrary. "This race is so idiosyncratic: You have the state's basic political DNA butting up against a climate that is better for Democrats, butting up (against) a Republican with extremely unique baggage. You have the disparity in the campaign finance, 10-to-1."

"All of that makes it very difficult to pinpoint exactly what is going to happen," he added.