The signs are everywhere that the 2020 Democratic presidential field will be much larger than usual — maybe larger than ever.

Barely a year into Donald Trump's presidency, one declared candidate, Rep. John Delaney, D-Md., is already running ads in Iowa. Julian Castro, the former HUD secretary, is telling reporters to consider him a White House prospect as he travels to New Hampshire. And former Attorney General Eric Holder is hinting he might be interested. These are just the most recent developments.

The list of would-be Democratic candidates is exhausting to recite, ranging from a two-term vice president, Joe Biden, to the mayor of the nation's 49th-largest city, Mitch Landrieu of New Orleans, with about two dozen others in between.

The volume and intensity of their early posturing speaks to the extraordinary energy of the party's grass roots and a widespread belief among Democrats that President Donald Trump will be beatable in '20. It's also the result of a vacuum at the top — there's no Hillary-esque heir apparent this time — and a sense that in the Trump-era, old rules and assumptions are up for grabs.

The last time so many Democrats were lining up to run was in 1976, the first election held after the Watergate scandal forced Richard Nixon from office. There are parallels between then and now that are worth considering, especially since the chaos of '76 ultimately produced a most improbable president.

The '76 campaign began against a backdrop of destabilizing political turbulence and national division. Watergate had instilled a new cynicism in the electorate, and distrust of the political system was reaching previously unimaginable levels. There was also the failure of Vietnam and the rise of a new breed of cultural activism focused on women, minorities and gays.

Much of this was a source of energy for Democrats, who looked toward the presidential election with optimism. The Republican Party's image was in tatters and the GOP was facing a damaging primary war between President Gerald Ford, Nixon's unelected successor, and former California Gov. Ronald Reagan. After eight years of Republican rule, it seemed like America was ready to give the loyal opposition a chance.

The most formidable figure in Democratic politics was Sen. Ted Kennedy of Massachusetts, who was 44 at the time. But Chappaquiddick — in which a young campaign aide was killed when Kennedy drove off a bridge — was still a fresh memory, and when he chose not to run it was as if everyone else looked around and wondered: Why not me? Rules changes that added primaries to the calendar and stripped even more power from party bosses only enhanced the appeal.

Each candidacy had its own theory. Sen Henry "Scoop" Jackson of Washington was both a union man and an ardent Cold Warrior. Sen. Birch Bayh of Indiana boasted a liberal record and a look made for the television age. Fred Harris of Oklahoma was a prairie populist stoking a peasants' uprising ("The issue is privilege"). Kennedy-in-law Sargent Shriver came with a touch of Camelot. There were others, too, many others: Mo Udall; Terry Sanford; Milton Shapp; Walter Mondale; George Wallace; Lloyd Bentsen; Frank Church; and Jerry Brown all competed, and hovering just out of sight was Hubert Humphrey, the nominee from '68, waiting for a stalemate that would let him ride to the rescue.

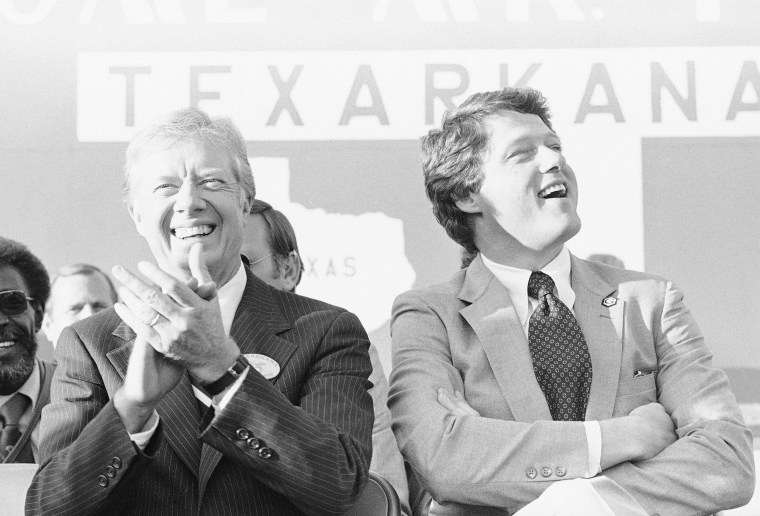

Then there was the man from Plains. Jimmy Carter was out of a job, term-limited after four years as Georgia's governor, when he set forth to run for the Democratic nomination. He was largely unknown and written off by the few reporters who bothered to cover him. With so many weighty national figures in the mix, why would anyone take this peanut farmer seriously?

To Democratic voters, it turned out, Carter's backwater roots and seeming lack of artifice were an exhilarating match for the moment. "If you support me," he told them, "I'll never make you ashamed. You'll never be disappointed. I have nothing to conceal. I'll never tell a lie." Vietnam and Watergate were recent and raw; Carter was offering himself as the antidote to all of the scheming and secrecy that had driven the country off course.

He broke out early in Iowa and New Hampshire and never stopped winning. A key test came in the Florida primary against George Wallace, the segregationist governor of Alabama who was trying to rally his base of blue-collar whites once more. These were voters who'd been born Democrats but who'd drifted to Nixon and the GOP in the last decade, and Carter was determined to win that back. He was Wallace's opposite on race and had appointed a record number of blacks to his administration in Georgia, but like Wallace, he was running as an outsider against the political establishment. To the Wallace crowd, Carter offered a new deal. "This time," his ads said, "don't send them a message. Send them a president." He won Florida and Wallace was done.

Carter's opponents howled that he was vague on the issues, adjusting his message to soothe whatever audience he was in front of. That didn't stop him, though, and after the final day of the primaries he had cleared the magic delegate number and was the party's presidential nominee.

A few months after that, he was elected president.

In any other moment in history, Jimmy Carter's presidential campaign probably would have ended on the same footnote as it began. But the unusual conditions that gave rise to that massive roster of candidates also ended up powering Carter's candidacy in a way that defied all expectations.

Times are different now, of course, and the Democratic Party has changed — more coastal, more upscale, more diverse. It's also much harder in our interconnected world to hide in plain sight as Carter did. Still, come 2020, there may be more than a whiff of '76 in the air. Right now, it's the usual suspects — Biden, Elizabeth Warren, Bernie Sanders and the rest — who get most of the attention, but is there another man (or woman) from a place like Plains who might capture the moment and catch fire?

In the same way Carter made a socially acceptable outsider's pitch to the Wallace crowd, perhaps there's a Democrat from Trump Country who could do the same with the voters Hillary Clinton dismissed as "deplorables." The two-term governor of Montana, Steve Bullock, enjoys roughly the same national profile Carter did in 1976. Or what about another Georgian — say Sally Yates, the former deputy attorney general, who might connect with the wave of feminist activism unleashed by Trump's presidency?

When Carter broke out four decades ago, pundits kicked themselves for not seeing it coming. The logic, in hindsight, was obvious. Ultimately, if there is another Carter on the horizon, we probably won't know until it happens. Who knows, maybe it will even be John Delaney.