In West Virginia and Indiana, the Republican Senate primary fights have morphed into multi-candidate battle royals with the combatants focused on one mission: out-Trumping their opponents.

In Indiana, the Republican hopefuls are sporting MAGA hats and nominating President Donald Trump for the Nobel Peace Prize. In West Virginia, they are bragging about who endorsed the president first and talking about “swamp people” in Washington.

Tuesday’s primary votes will tell us if the strategy worked, but some key numbers in the states explain all the one-Trumpsmanship – at least for primary season.

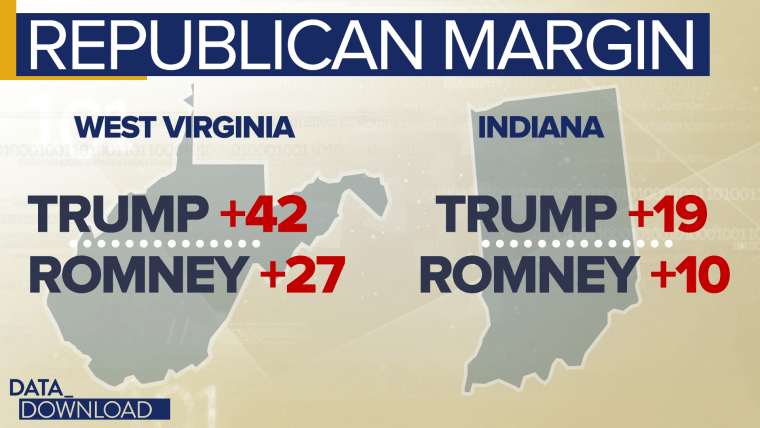

For starters, both states not only went for Trump in 2016, the president did much better than 2012 Republican Presidential Nominee Mitt Romney.

Trump performed 9 points better than Romney in Indiana and 15 points better than Romney in West Virginia. Both states are rich in a voter group that was especially good to Trump in 2016 and who stand strongly behind him still: working class whites. Whites without a college degree make up 61 percent of the 25-and-older population in Indiana and a remarkable 74 percent of that group in West Virginia. Nationally, the figure for that group is only about 42 percent.

So, those two numbers make a pretty good argument for Republicans staying as close as they can to the president in those states – particularly when you consider that each state has three legitimate GOP candidates dividing the vote.

But after Tuesday, the Senate races in both those states will cast an eye toward November’s general election, and there the I’m-with-Trump strategy could get a little more complicated even in places that appear to be deep Trump country.

Donald Trump’s 2016 win didn’t just rely on Republican voters, it relied on people who were more about supporting the man than his party – voters who are truly Trump supporters first and Republicans, or something else, second.

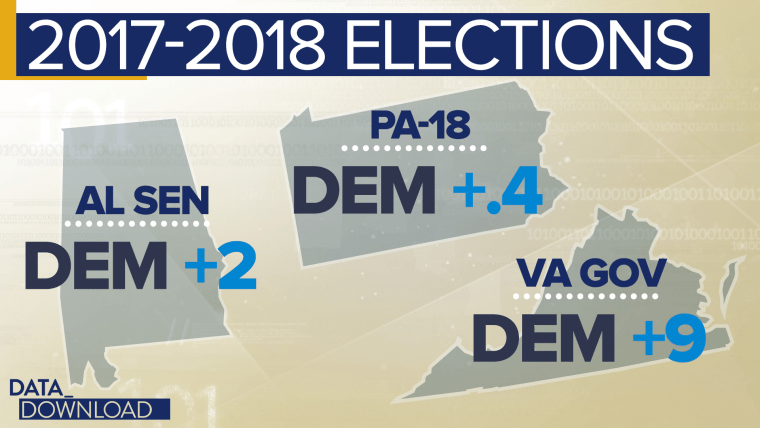

Will those voters come out when Trump is not on the ballot? The elections of the past year suggest the Trump bump may not be a transferable quality.

In Pennsylvania 18, a congressional district Trump won by 20 points in 2016, Democrat Connor Lamb eked out a victory in a March special election. Last December, Democrat Doug Jones won the Senate special election in Alabama, even though Trump carried the state by 28 points in 2016. And last November Democrat Ralph Northam won a surprisingly easy victory in Virginia’s gubernatorial race in an election most thought would be very close.

On top of that, while many people look back on 2016 as the year of Trump, there were two candidates on the ballot. The election was also about Democrat Hillary Clinton, a candidate many voters struggled to get behind. She won’t be on the ballot in November either.

Back in 2012, Democrat Barack Obama did much better in Indiana and West Virginia than Hillary Clinton did in 2016.

Obama ran seven points better than Clinton in Indiana and nine points better than Clinton in West Virginia. Those are big differences. Did Trump pull voters away from the Democratic candidate on those states, or did Clinton simply lose them? It was likely a bit of both. Regardless, neither of the 2016 presidential candidates will be on the ballot Tuesday or in November.

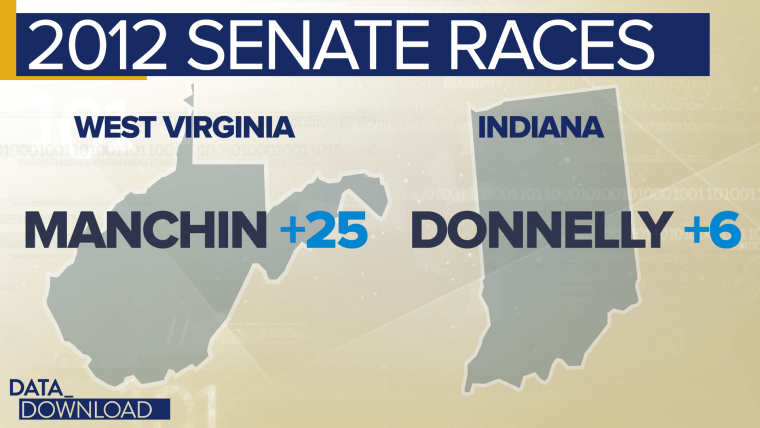

Who will be on the ballot? On the Democratic side, you will have two incumbent senators, Joe Donnelly in Indiana and Joe Manchin in West Virginia, who won their seats by comfortable margins in 2012 even as their states went for Republican Mitt Romney by double digits.

Donnelly won Indiana by 6 points, even as Romney won the state by 10. And in West Virginia, Manchin won by 25 points, while Romney won by 27 points. In fact, Manchin won all but four of West Virginia’s 55 counties.

In other words, both senators have done fairly well with ticket-splitting voters. They likely won’t be pushovers and have had years to craft their political messages and personas.

In short, the GOP Senate hopefuls in Indiana and West Virginia may be tying themselves to Trump with the hopes of rerunning the 2016 presidential race in their states. But that may prove difficult and the names on the ballot this fall will likely be the most important determining factor in the Indiana and West Virginia Senate races. It’s hard to make yourself into Donald Trump – or a known opponent into Hillary Clinton.