“There ought to be a law.”

That’s a common American refrain on a long list of issues, from unsolicited phone calls to opioid abuse, and Congress often acts. But this week’s school shooting in Parkland, Florida brings attention to one prominent issue where that cause-and-effect rule no longer seems to be true: gun laws.

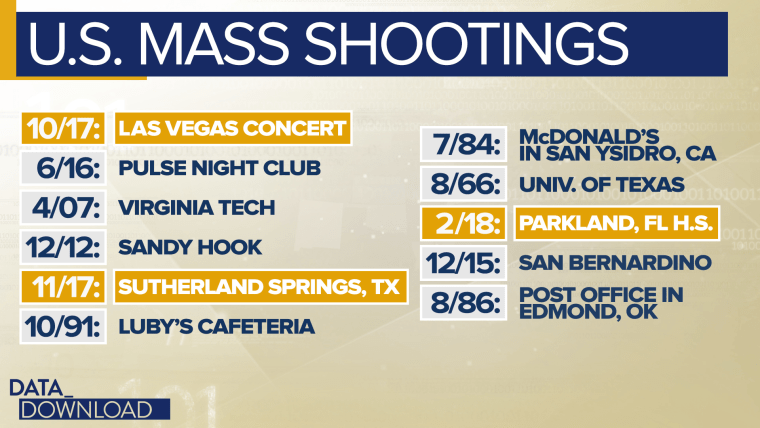

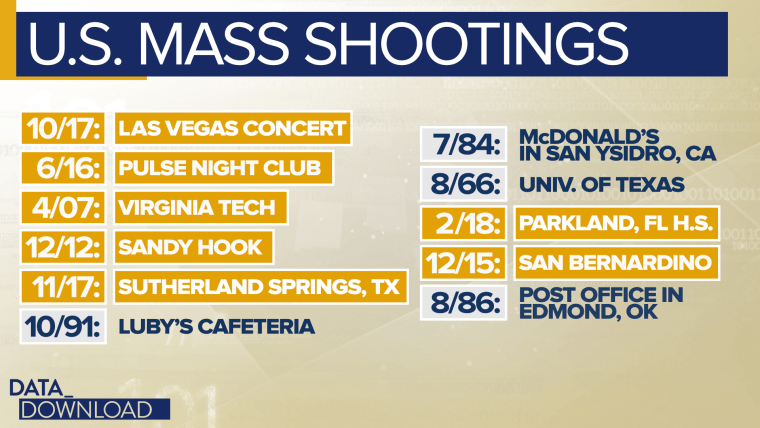

Three of the 10 biggest mass shootings in U.S. history have now taken place in the last five months and the question, as it always is after the all-too-common events, is will Congress step in?

The answer in recent years has been no, of course. After October’s mass shooting at a country music concert in Las Vegas, the deadliest in U.S. history, there was initially talk about passing a law banning “bump stocks,” the device that shooter used to fire into the crowd more rapidly. But momentum for a rule change or new legislation slowly waned. Nothing passed.

It wasn’t always this way. There was a time when gun incidents or crime trends brought legislative reactions from Washington.

In 1934, Congress passed and President Franklin Roosevelt signed the National Firearms Act in a response to the rise of organized crime and gangster culture that grew out of prohibition. The law slapped a $200 tax on automatic weapons as well as sawed-off shotguns. That tax would be equal to about $3,500 in 2018 dollars, when adjusted for inflation. The law still exists today, but the tax is unchanged at the $200 level.

In 1968, the Gun Control Act was passed after the assassinations of John F. Kennedy, Robert Kennedy Martin Luther King Jr. The law expanded licensing requirements, banned mail-order rifle sales and grew the list of people who could not purchase a gun to include most convicted felons and mentally ill people.

The Law Enforcement Officer’s Protection Act, which outlawed armor-piercing bullets, came in 1986 as city gangs and drug violence came to city streets.

And 1994 brought the enactment of both the Brady Handgun Violence Protection Act and the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act. Those laws gave us the five-day waiting period for handgun sales, the “assault weapons ban” and the National Instant Criminal Background Check System.

The laws arose out of the proliferation of cheap handguns, the attempted assassination of Ronald Reagan a dozen years earlier, and an outburst of workplace mass shootings in the late 1980s and early 1990s. (That was the period that brought us the phrase “going postal.”)

The point here is not that those laws were the perfect responses or even the “correct” responses. But they were, without question, responses. They were attempts by Washington to do something in the wake of events or trends that upset the American public. They were examples of that traditional American response, “there ought to be a law.”

But in the years since, that has changed on guns. Consider the numbers:

Since 1995, there have been 96 mass shootings in the United States, according to a tally from the Washington Post – including seven of the 10 deadliest. And the data show that the number of incidents and deaths has been climbing by the decade since then.

There have been 424 mass shooting deaths since 2010, according to the Post’s data. That means, even if there is not a single mass shooting through all of this year and 2019, the current decade will still have produced far more mass shooting deaths than the previous 10 years.

And there hasn’t been a real pattern to the mass shootings in terms of location. Few places or groups have been spared.

There have been office shootings, school shootings, university shootings, church shootings, concert shootings, restaurant shootings, and nightclub shootings. There’s been a military base shooting, a movie theater shooting, and a car wash shooting. Members of Congress have been targets, as have children.

And yet, through all of that, the Gallup polling numbers on wanting gun laws that are “more strict” have hardly moved. Since 2000, they follow a standard trend. After an attack, support for tougher rules tends to rise into the high 50s or even 60 percent, but the numbers later settle back to somewhere in the 40s as the weeks and months pass. The figures were much higher in the early 1990s.

In other words, over the last two decades, the gun debate has gone from “there ought to be law” to “it’s too soon to talk about legislation” to “you can’t legislate the problem away.” That’s happened as mass shooting incidents have proliferated.

In the particular case of gun laws, the sheer number of incidents seems to have made action less likely. So much so that after this week’s shooting in Parkland, the assumption in Washington is Congress will not act because, in many ways, the shooting was so relatively common. And an event that would have dramatically shaken the country and had it asking “why?” a few decades ago has elicited a different question in 2018: “Why should the legislative reaction be different this time?”