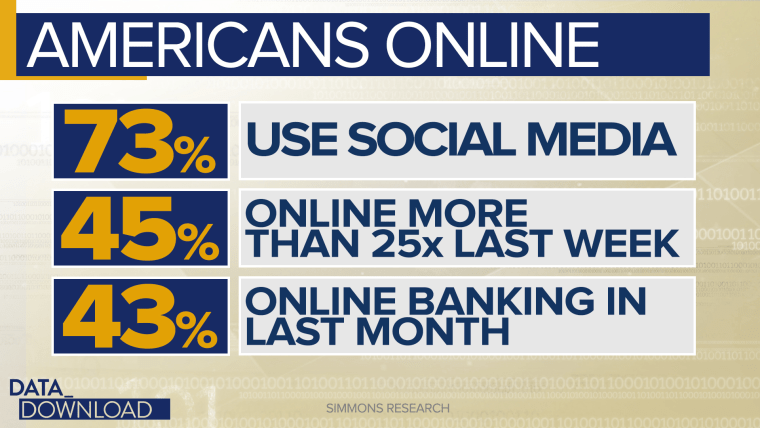

As Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg testified before Congress this week, voters had good reason to pay attention. Americans are online a lot: Seventy-three percent of us use social media, 45 of us went online more than 25 times last week, 43 percent of us did some form of online banking last month, according to Simmons Consumer Research. And we hold deep concerns about what happens to our personal information online.

In a country divided on policy, politics and culture, concerns about privacy emerge as something of a great uniter, Simmons data suggest. Americans of all stripes share a feeling of helplessness when they post personal information online. They want more personal control over information companies have gathered on them. And they don’t place a lot of faith in the federal government to make the best decisions about protecting their privacy.

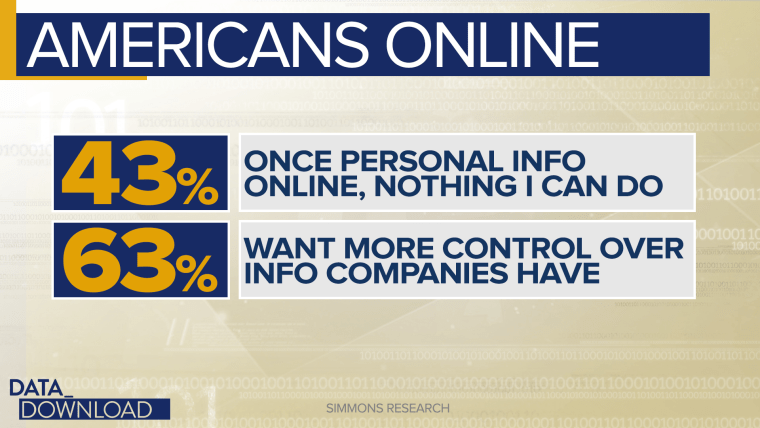

More than four in 10 Americans say that once a piece of personal information is online there’s nothing they can do about it. Six in 10 say they want more control over the information companies might have on them. And only 18 percent say they trust the federal government to make the best decisions about how to protect their privacy.

That’s a lot of misgivings and mistrust.

It’s not enough to scare us off of our electronic devices, at least not yet. Only 22 percent of Americans say privacy concerns have caused them to reduce internet usage. But the broad agreement on the security and use of personal data online shows this is a Washington debate that people care about.

The numbers aren’t monolithic, particularly when you look at the data by age. There are some noteworthy generational gaps between Boomers, for whom the online realm was a late addition to their world, and Millennials, who are “digital natives.”

Among people ages 25 to 34, the Millennials, 41 percent say they “feel like they have a fair amount of control over the personal information” that can be found about them online. With those ages 55 to 64, the Boomers, only 26 percent feel that way.

That’s a 15-point gap and it may have something to do with the difference between growing up with the internet and having to adjust to it. There’s a reason younger people often get calls from their parents to serve as “tech support.” What’s less clear is whether that Millennial confidence in warranted.

The Millennial age group is also more likely to say the information about them online is “relatively harmless,” 47 percent believe that. Only 30 percent of the Boomer age group believes that to be true.

Some of that split may be about the kind of information that those age groups are thinking about, photos and social media posts on one hand versus credit scores and banking records on the other.

And the education divide rears its head in these numbers. The Simmons data shows that those with a college education are much more likely to look up a company online before sharing personal information than those without a degree.

More than half of those with a bachelor’s degree, 51 percent, say they check out the website that wants their information before they enter it. The number for those without a degree is 35 percent.

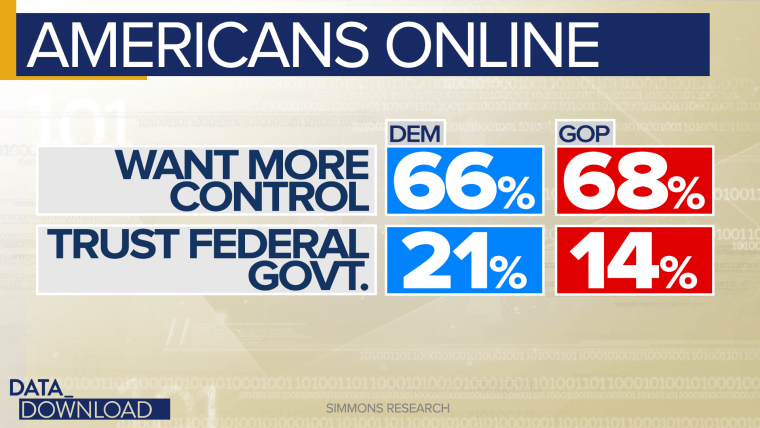

But when you look at the most politically meaningful divide in the nation, the partisan split between Democrats and Republicans, the differences in the numbers fade. For the most part, Red and Blue America are in agreement on concerns about online privacy.

Democrats and Republicans are separated by four points or less on questions about their personal control over online information. And two-thirds of the members of both parties say they want more control over their personal data.

Furthermore, while Democrats are more likely to say they trust the government to make the best decisions about how to protect their privacy, the number is still very low — 21 percent for Democrats versus 14 percent for Republicans. And both groups, by the way, fall almost exactly in line with the national average on whether they are using the internet less because of worries about online privacy.

How often do you see members of the nation’s two major political parties show that kind of agreement on anything, particularly a hot topic in the news? That’s one reason why this issue isn’t likely to go away.

But this issue is not necessarily a slam dunk for Washington.

Americans are nervous about sharing information online. They want more control over their data. And they aren’t especially eager to scale back on the online time that has become a very big part of their lives. But they’re not really sure they trust the government to figure out the answer.

In other words, Democrats and Republicans agree that they want something done, but the question echoing through the halls of Congress is: “What now?”