Legal analysis

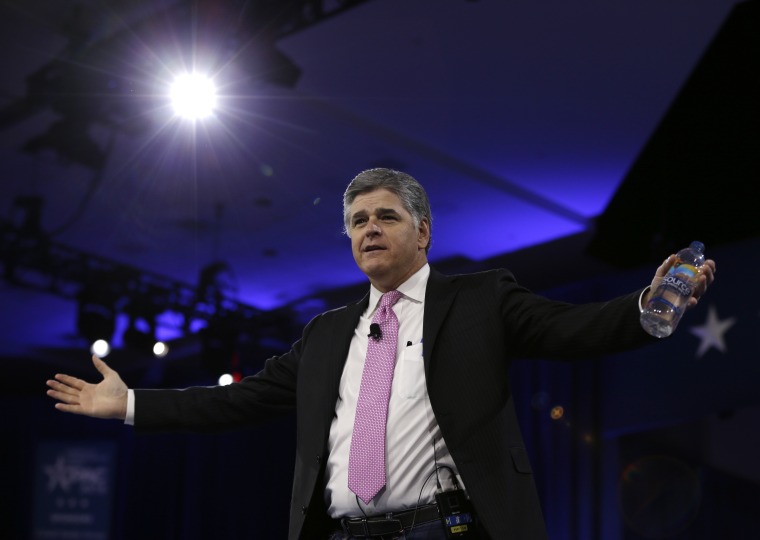

Michael Cohen has said he had only three clients in 2017 and 2018: President Donald Trump; Elliott Broidy; the former deputy finance chairman of the Republican National Committee; and, until yesterday, someone Cohen did not want to identify. But in court on Monday, Cohen's lawyer was forced by the judge to reveal the client's name: Sean Hannity, the Fox News host.

Hannity quickly addressed the news on his radio show, claiming that he never retained Cohen in the "traditional" sense, but that they still had attorney-client privilege.

"Michael never represented me in any matter, I never retained him in the traditional sense as retaining a lawyer, I never received an invoice from Michael, I never paid legal fees to Michael," Hannity said. "We definitely had attorney-client privilege because I asked him for that but, you know, he never sent me a bill or an invoice." Hannity also recalled that he "might have handed him 10 bucks."

Hannity later tweeted that he "assumed" his conversations with Cohen "were confidential, but to be absolutely clear, they never involved any matter between me and a third-party." The conservative Fox host said the discussions were "almost exclusively about real estate."

It's the classic test on the law school professional responsibility exam: A person approaches a friend-attorney at a cocktail party and requests legal advice, without a written retainer agreement or payment of a fee. Does an implied attorney-client relationship arise?

The ethics opinions are similarly full of examples of a would-be client insisting a law firm took his case, while the firm says there were only conversations, not the creation of an attorney-client relationship. The Hannity-Cohen situation is the reverse: The attorney is insisting there was a relationship; the client is minimizing that.

In New York, the formation of the attorney-client relationship focuses upon the client's reasonable belief that he is consulting a lawyer, in his capacity as a lawyer, and his manifest intent to seek professional legal advice. The formality of, say, a written agreement or an invoice, is not an essential element in the employment of an attorney, though the attorney is encouraged to reduce agreements to writing.

The federal court in the Southern District of New York will look at the words used, and the conduct of the attorney and the putative client. Formality is one of several factors considered by the courts, including the existence of a signed fee arrangement, payment of a fee, and whether the attorney actually represented the individual at something like a court hearing or deposition. Another important factor is whether the supposed client reasonably believed that the attorney was representing him.

But the Southern District has cautioned that a party's one-sided belief that he is represented by counsel does not automatically create an attorney-client relationship unless there is a reasonable basis for that belief by the "client."

Ultimately, to establish an implied attorney-client relationship, the "client" must show that he submitted confidential information to a lawyer with the reasonable belief that the lawyer was acting as his attorney. When that happens, a court should at least enforce the obligation of confidence, irrespective of the absence of a formal attorney-client relationship.

Hannity is right that if he reasonably expected he was seeking and receiving legal advice, an implied attorney-client relationship may be inferred from his interactions with Cohen. That implied relationship, if it existed, at least imposed upon Cohen a duty of confidentiality, and raised the possibility of attorney-client privileged communications.

So why was the federal court able to force Cohen's attorneys to reveal the relationship?

The attorney-client privilege only protects confidential communications between client and attorney for the purpose of obtaining or providing legal advice. The identity of a client, or the fact that someone has become a client, is information that an attorney normally may not refuse to disclose.

Attorney-client privilege is not the same as the attorney's ethical duty of confidentiality. The ethical duty of confidentiality is much broader than information protected by the attorney-client privilege.

Indeed, attorneys have risked being held in contempt of court, rather than disclose the identity of their clients. Cohen was caught between Scylla and Charybdis: The privilege did not give him the legal right to refuse to disclose his client's identity. But disclosure potentially violated his ethical obligation of keeping his client's identity secret — especially when the client may have asked Cohen to keep it secret.

Danny Cevallos is an MSNBC legal analyst. Follow @CevallosLaw on Twitter.