WASHINGTON -- This week, the Democratic Party in South Dakota announced it was closing its last two offices in the state. The move surprised some analysts and brought criticism from some quarters as an example of Democrats abandoning difficult political terrain.

But a look at the numbers over the past 20 years shows some of the thinking behind those moves. The changes in culture and politics in that time have left an election map that is full of communities that are either deep red or deep blue, with little room for the political space between.

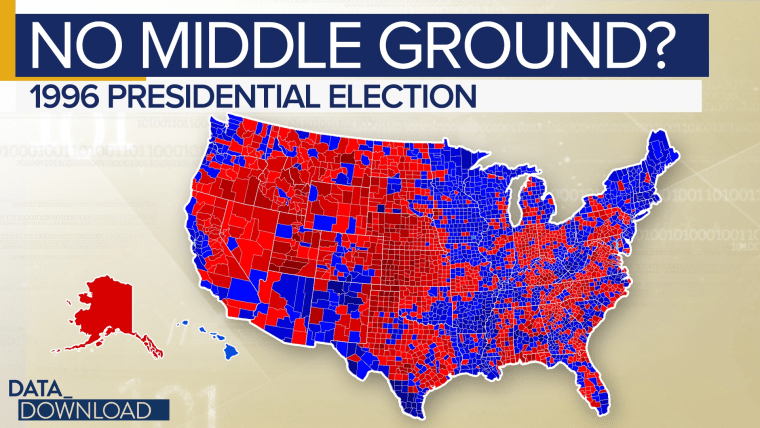

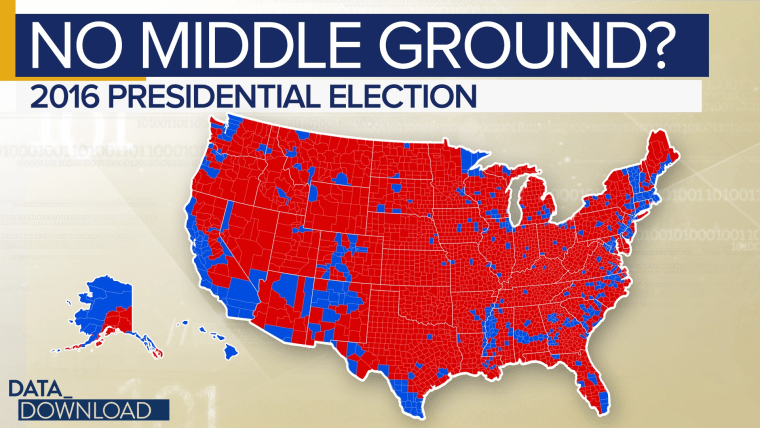

The presidential elections of 1996 and 2016 offer some remarkable evidence.

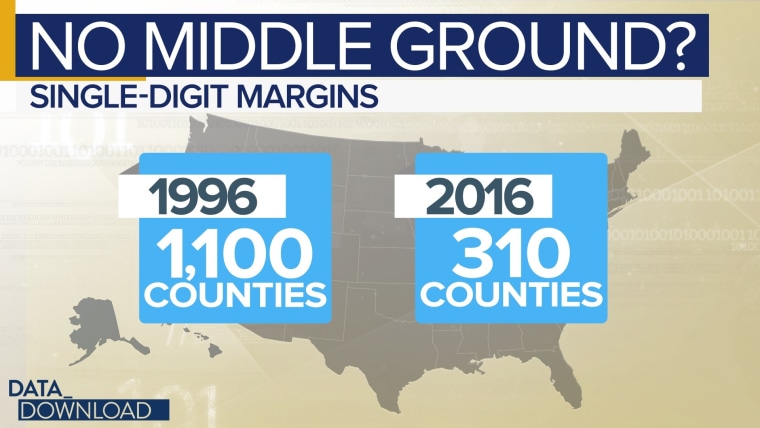

In 1996, President Bill Clinton won re-election by a large margin, 8.5 percentage points, but the results at the country level showed a much more “purple” map. In more than 1,100 counties, the margins for Clinton or his opponent Bob Dole were within single digits.

In 2016, the national results were very tight; Hillary Clinton won the popular vote by about 2 points over Donald Trump (and, of course, Trump won the Electoral College vote). But there were only 310 counties where the margins for either candidate were in the single-digit range.

That means in 20 years the number of “competitive” counties declined by about 72 percent. That’s a huge drop, but it’s even more extraordinary when you consider than the 2016 election was much closer nationally than the 1996 election.

It’s a set of numbers that show how much the territory in the political middle has shrunken, literally. Yes, 1996 third-party candidate Ross Perot may have had some impact on those numbers around the edges, but his net impact was not large and the data show something bigger going on.

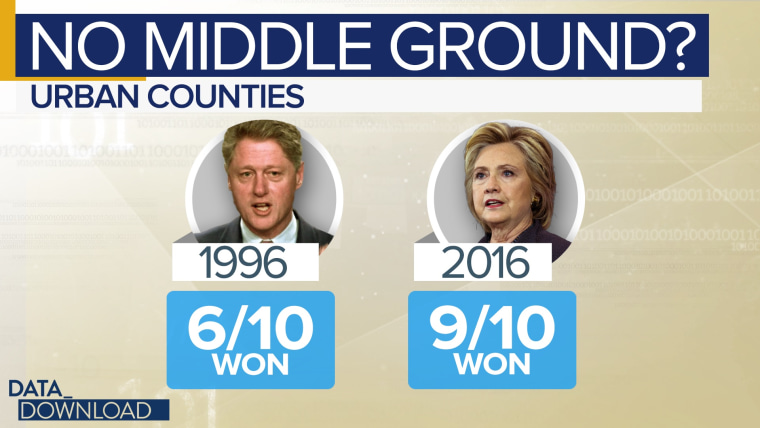

Driving the shift seems to be a familiar culprit, the growing divide between urban and rural America.

In 1996, Bill Clinton did well in urban communities. He won six of the 10 largest vote-producing counties. But in 2016, Hillary Clinton did even better. She won nine of the 10 biggest vote producers – all but Maricopa, the home of Phoenix, which she lost by just three points.

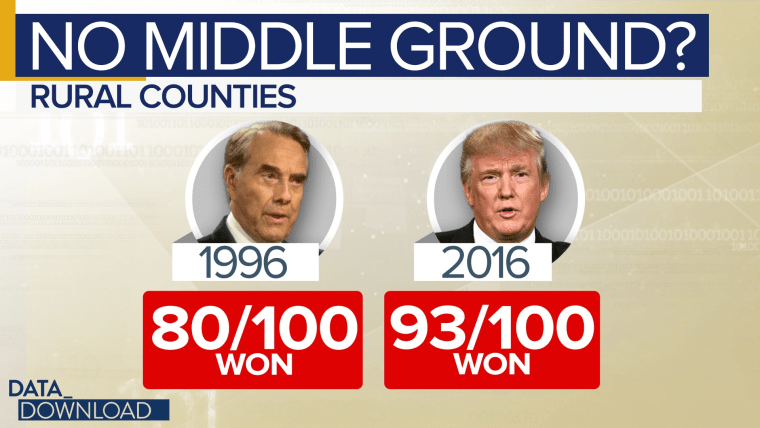

The reverse is true in rural places. In 1996, Bob Dole of 80 of the 100 smallest vote producing counties. But in 2016, Donald Trump won 93 of the 100 smallest vote producers.

Urban areas have gotten more blue and rural ones have gotten more red.

And the impact of that shift is even more apparent when you look at the margins in some of the places. Consider what's happened in the counties holding some of the nation's biggest cities.

In 1996, Marion County, home of Indianapolis, went for Dole by 3 points. In 2016 it gave Hillary Clinton a 22-point margin. Dole won Dallas County in Texas by one point. Hillary Clinton won it by 26 points. And Mecklenburg County, home of Charlotte NC, voted for Bill Clinton by a narrow three-point margin in 1996, but voted for Hillary by 29 points.

Those are big swings toward the Democrats in 2016 and remember, Bill Clinton won the popular vote by a much larger margin in 1996.

Meanwhile, the margins have moved massively in the other direction in rural places.

In 1996, Dole won DeSoto County Florida, Dodge County Wisconsin and Ionia County Michigan each by one point. In 2016, Trump won them by 27 points, 29 points and 31 points respectively. Those counties and others like them were key elements of Trump’s rural surge that carried those states.

Does all of this mean that candidates and parties shouldn’t try to win over voters that aren’t necessarily aligned with them? Of course not. Building an actual working majority in politics requires reaching beyond just one’s base.

But time and money are limited and these numbers suggest that in very real terms that there are fewer and fewer places for candidates to target swing voters who might be receptive to their messages. It’s a lot easier to find areas full of “base” supporters where candidates can focus on boosting turnout.

In other words, the middle ground of American politics may be literally disappearing, but, to a large extent, candidates and parties are playing on the terrain they’ve been given.