WASHINGTON — Friday brought some welcome employment news as the economy added about 560,000 new jobs in May, knocking the unemployment rate below 6 percent. Combined with the latest news about falling Covid-19 case numbers and increasing numbers of Americans' getting vaccinated, many analysts hope for an economic boom this summer as a full reopening draws nearer.

But it might not be that simple. There are signs that a broader shift might be remaking the economy in ways that make it harder to see the road ahead.

Let's start with last week's job numbers. They were clearly a good sign overall.

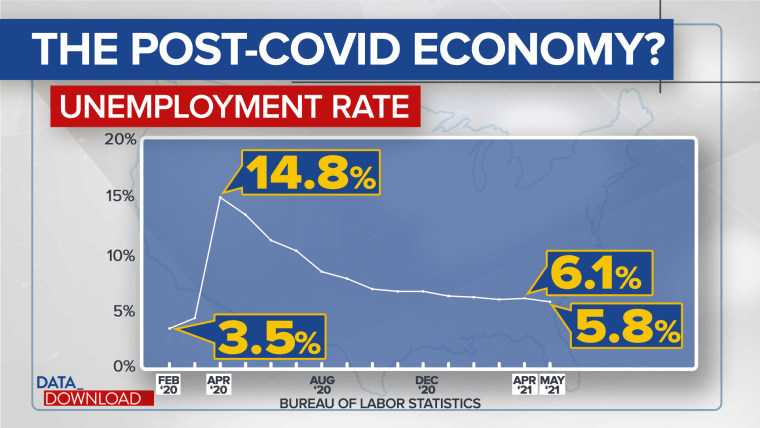

The unemployment rate fell to 5.8 percent in May, compared to 6.1 percent in April. And compared to May 2020, when the economy was still deep in its Covid-19-induced haze, the rate is down by more than 7 points.

The unemployment number is still not down to its remarkably low pre-pandemic number of 3.5 percent, but the trend is good, and 5.8 percent isn't a terrible number for an economy that spent 2020 being pounded by a pandemic. There is a real reason to feel optimistic about the May unemployment rate.

But the real story of the Covid-19 economy may be seen in a less-discussed number. While people tend to focus on the unemployment rate, that is based on the number of working-age Americans actually seeking jobs (the number of people actively "participating" in the labor force), and it looks a lot different today than it did a year ago.

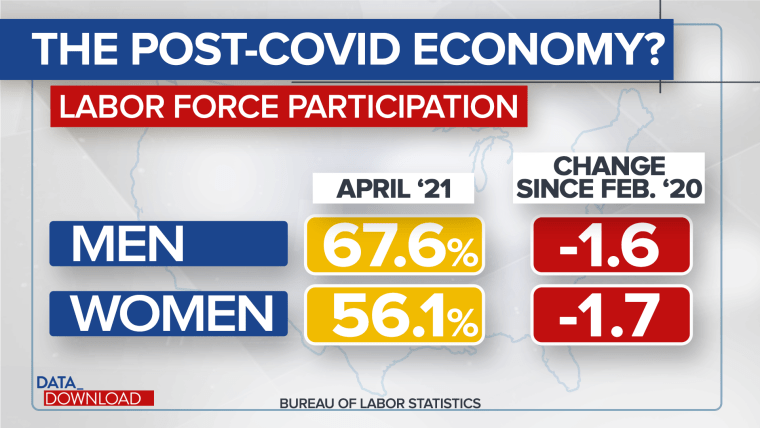

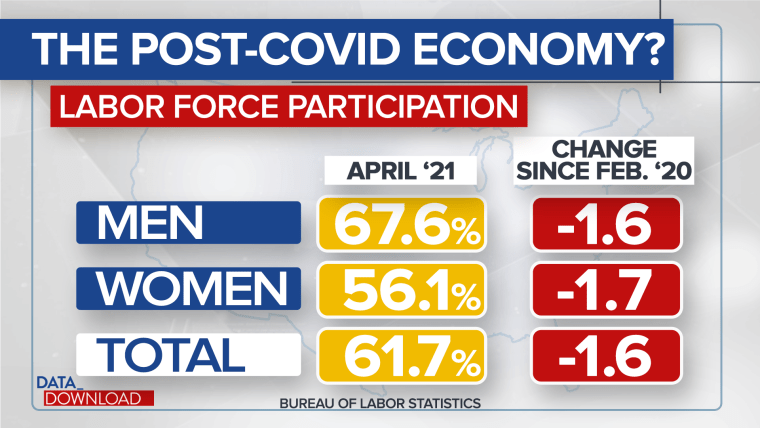

Overall, labor force participation is down by more than 1.5 percentage points since the pandemic began (and the number didn't really change from April to May). That might not sound like a lot, but remember that we are talking about the total number of Americans looking for jobs. That's a pretty big pool of people, and in real terms, the drop reflects a decrease of about 3.5 million people.

The declining percentage is slightly higher among women, but both sexes have dipped, and the drops among both men and women show how deeply rooted the change might be.

It's not strange for labor force participation to drop during a recession. Workers get discouraged and leave the job pool. And labor force participation has been falling for decades as the nation ages. People eventually age out of the workforce and retire.

But the size and suddenness of the latest drop are remarkable, and the current figures are extremely low. Just how low becomes noticeable when you look at the historical trend.

The last time labor force participation was this low was more than 40 years ago, in January 1977. That means current labor force participation is lower than it was during the tech bust or just after the Sept. 11, 2011, terrorist attacks or during the Great Recession.

Consider all the changes in the economy in the last 40 years. There were no internet or smartphones, and, more important, women hadn't yet been fully integrated into the workforce in the late 1970s. When women fully entered the labor force, the participation rate rose sharply, by more than 17 points, from 1960 to 2001.

In other words, the U.S. workforce is radically different today than it was in 1977, and the fact that labor force participation is as low as it is might mean a serious economic change is afoot.

Some economic analysts argue that Covid-19 relief checks are discouraging people from work or that distance learning in grades K-12 is keeping some parents at home to watch their kids and that those factors may be playing some role.

But the pandemic has also changed how we do things, from more online shopping and food ordering to less commuting and fewer theater visits. The net result of many of those changes was more automation and less personal interaction — fewer counter workers and waitresses, cabdrivers and bartenders. In the May labor report, leisure and hospitality unemployment was still in double digits.

The question is whether we are seeing long-term behavioral shifts or short-term alterations.

The way that question is answered will have a big impact not just on the number of people who are unemployed but perhaps on the number that is even looking for jobs to begin with.

CORRECTION (June 6, 2021, 9:25 p.m. ET): A previous version of this article misstated when the unemployment rate was last near its pandemic high. It was in May 2020, not May 2021.