WEST POINT, N.Y. — The Army is turning to its most junior enlistees for a new project aimed at combating a growing number of cultural problems within the ranks.

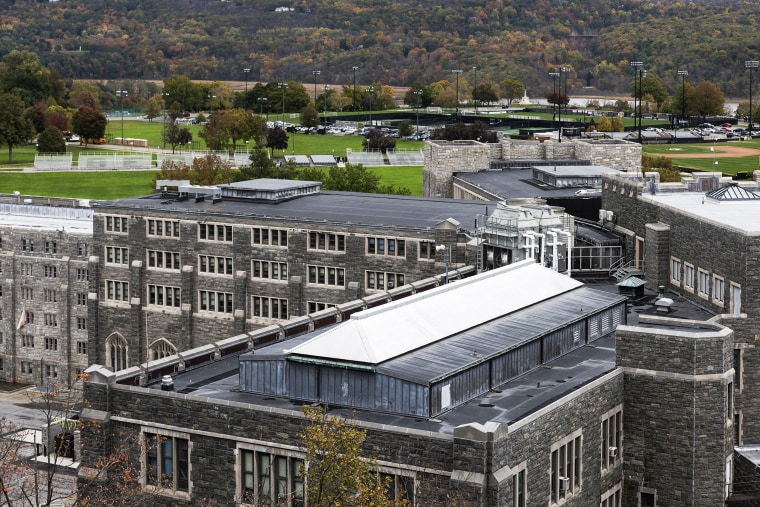

Last week, soldiers from around the country who have served for less than three years were flown to West Point for weeklong discussion groups with officers as part of a new Army effort, named the People First Solarium, aimed at finding solutions to three issues: sexual assault, suicide and racism and extremism.

Participants took part in three groups focusing on those issues and they discussed how they have been affected by them and how the Army could better address them.

“We’ve done a lot of programs over the years to get after harmful behavior without a whole lot of change,” said Christopher Lowman, the acting undersecretary of the Army, adding that the program is “an acknowledgment” that the harmful behaviors break down trust and unit cohesion, and have been a challenge in the Army “for a long time.”

“That’s what this week’s been about — us to understand the harmful behaviors from their perspective and how they would like the Army to address it,” Lowman said.

Events of just the past year underscore the depth of these cultural issues within the ranks — from addressing racial unrest across the country to the disappearance and death last year of Vanessa Guillén, a 20-year-old Army specialist believed to have been killed by a fellow soldier at Fort Hood, Texas.

That case prompted an independent review of the command climate and culture at Fort Hood as well as the Jan. 6 storming of the Capitol, where an analysis by NPR found that nearly 1 in 5 people charged for their alleged involvement were former service members.

According to Army leadership, about 30 soldiers out of 100,000 died from suicide over the past year, while 5 in 100,000 soldiers were affected by racism and extremism, and 256 in 100,000 soldiers were affected by sexual harassment and sexual assault directly.

Officials said the initial concept of the Solarium was born from a conversation with the Army's vice chief of staff, Gen. Joseph Martin, and then-Secretary of the Army Ryan McCarthy on addressing suicide in the ranks.

“We realized that we had to do something different,” Martin said. “We said to ourselves, 'What if we brought in some of the most junior soldiers in the United States Army and ask them for their perspective to better understand where they're coming from?'” Martin said.

“What we have right now isn’t working,” Martin told the soldiers during their initial People First Solarium briefing last Monday at West Point.

It's a feeling shared by outside experts with long experience in the Army. “None of these problems were created overnight and I don't think any of them are going to be solved overnight either,” said Diane Ryan, an associate dean for programs and administration at the Jonathan Tisch College of Civic Life and a retired Army colonel with a background in social and community psychology who taught at West Point for nearly a decade.

“These aren't necessarily new things," Ryan said. "They just maybe simmer under the surface for day to day, and then something significantly bad happens and we go, ‘Oh gee, I guess we still have a problem with that.' I feel like they reached a crisis point a long time ago and just haven't been able to crack those nuts.”

Discussions and proposed solutions

During the project, soldiers were joined in the groups by facilitators with backgrounds in behavioral science who helped moderate the discussions.

“At first I was a little nervous,” said Spc. Nicolas Rios, a New York Army National Guardsman. “But once I got to meet our team, and we started on Day One on Monday and we all started discussing, we were all pretty much open, everything out on the table,” he said.

Rios joined 100 soldiers who reflected a mix of race and gender as well as soldier performance with the goal of ensuring an accurate representation of the total Army population.

The Army's current Sexual Harassment/Assault Response and Prevention program, or Sharp, has long been criticized for its ineffectiveness. Following Guillén's death, McCarthy called out the program, saying it hadn’t achieved its mandate to eliminate sexual assaults and harassment.

“Most of the training that we do is really considered briefs,” Army Pfc. Ashlee Roy said. “It's more like … just a check off the box to get it done. It's not truly as in depth as it should be."

Army Spc. Haley Hilton, an Army reservist based out of Atlanta, said he experienced racism firsthand as a young soldier in Army dorms.

“I went to knock on a guy's door and he had like white power flags and like Confederacy flags and I was just scared,” Hilton said.

At the time Hilton did not inform her superior in the chain of command, thinking that since the flags were hanging in the soldier’s room nothing could be done.

One of the recommendations from Hilton’s group, which focused on racism and extremism, was making sure soldiers know what’s acceptable and what’s not.

“Maybe at the time I would have went to go tell an NCO or my leadership,” she said.

After a weeklong discussion, each group presented their findings to Martin, Lowman and Sgt. Maj. of the Army Michael Grinston.

According to a survey of soldiers who participated in the Solarium, 94 percent believed there should be a mechanism to confidentially report sexual assault or harassment outside of the chain of command.

Though more than 53 percent of participants surveyed agreed or strongly agreed that suicide prevention training was effective, one of the findings from soldiers who were focused on suicide was that young soldiers don’t have adequate training or the mindset for how to cope.

Other recommendations included peer evaluations to identify issues, more training sessions and peer-led training. There were also suggestions to re-evaluate the current training models and veering away from PowerPoints and focusing more on engagement. For sexual assault, soldiers recommended focusing more on healthy examples of relationships, communication and awareness.

Martin said the candid feedback was powerful.

“This is unprecedented,” Martin said, “We've never brought this cohort in to discuss these issues,” adding, "it was absolutely amazing how articulate they were, how well thought through their ideas were."

Communicating more effectively at all levels was a key takeaway for Grinston. “We can do better than what we've been doing in the past because of the soldiers and their candid feedback,” he said.

Lowman agreed. “I'm extraordinarily proud of these young people standing up and laying out for us, their insights, really unafraid,” he said. “I do not believe that after 33 years as department Army civilian, I've heard these challenges talked about in this fashion.”

“I think it was enriching not only for the soldiers, but also enriching for us,” Lowman said.

The recommendations will be incorporated into the Army’s People’s First Task Force along with other pilot programs already underway to develop and assess possible changes to policy and adjustments to soldier training.

“One thing I want them to take away is that they can go back, they don't have to wait for … the Army to come up with a policy for everything,” said Grinston. His hope is that those who participated in the Solarium will take what they’ve learned back to their units.

“That's what we want — we want them to go ahead and start it, and then maybe it'll evolve over time,” he said.