WASHINGTON — When the dust settled from the first round of the Senate battle over the filibuster, one man had clearly won: President Joe Biden.

The new president, a 36-year veteran of the Senate, has long believed in the principle of unlimited debate. But as many of his fellow Democrats clamored to kill the filibuster, silence was Biden's best friend.

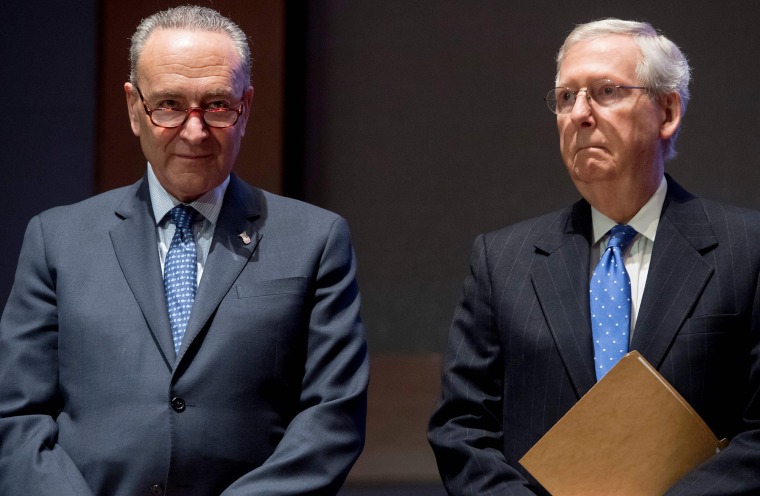

In sidestepping the fight publicly, Biden protected his political capital while reassuring both Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., and Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., that he could see both of their divergent points of view — and, more important, their political needs.

Jim Manley, who was an aide to Harry Reid, D-Nev., when he was the Senate majority leader, said Biden's handling of the filibuster debate demonstrates an understanding of how a president can and can't help himself by engaging on Capitol Hill.

"Presidents get entangled in internal Senate politics at their peril," Manley said in an email exchange. "Doesn't mean they can't talk privately, but he is playing this pretty close to perfect for right now by not putting a lot of pressure on Democrats."

The closest Biden got to taking a side was when White House press secretary Jen Psaki said his position "hasn't changed" — a tea leaf that Republicans could take as a sign that he wouldn't steamroll them and that Democrats could read as a harbinger of a possible future flip.

Biden is now in the White House, but his Senate record shows support for a minority's being able to hold up business. As a senator from tiny Delaware, he understood better than most how the institution's rules tilted toward small states and toward empowering both the minority party in general and the minority of senators on any given issue.

"This was never intended in any sense to be a majority institution," Biden said in a lengthy and effusive defense of the filibuster during floor debate in 2005. "History will judge us harshly, in my view, if we eliminate over 200 years of precedent and procedure in this body and, I might add, doing it by breaking a second rule of the Senate, and that is changing the rules of the Senate by a mere majority of the body."

What Biden actually thinks about the filibuster — or what he has said over the course of decades about it — may not be the only factor in his thinking going forward. Things have changed. He now represents the whole country rather than Delaware, he now sits in the White House rather than the Senate, and he is now trying to pass his own agenda rather than protecting his ability to kill the agendas of others.

He could cite any of those reasons to flip down the road.

It makes little sense for a politician to change a position any earlier than necessary. For now, he has spared himself the political cost of talking too much about senators' talking too much. That's the move of a president who understands how senators think.

Psaki's construction reflected two realities: Biden gets the Senate, and he can count. He doesn't have the votes to take the filibuster away from Republicans right now — even if he wanted to — and a failed effort to jam a change through would only cost him among lawmakers in both parties over the long term.

Instead of squandering his capital, he chose to build it. Most of the Senate doesn't want this fight — even if that means all of the Republicans and only a handful of Democrats.

For senators who are willing to buck the Democratic Party to keep the filibuster, like Joe Manchin, D-W.Va., and Kyrsten Sinema, D-Ariz., it is reasonable to assume that there are others who agree with them but do not want to say so publicly for fear of a backlash from activists.

Manchin and Sinema provide cover not only for other Democrats but also for each other; as long as they stand together, neither of them will be the sole focus of vitriol from the party's left.

And Biden and the two senators provide cover for one another. It's harder for activists to be angry with Biden if he doesn't have the votes, and it's harder for them to be angry at the senators if the White House has indicated that Biden still agrees with their position.

And all of that gives cover to McConnell.

He cited Manchin and Sinema on Monday night when he dropped his insistence that rules organizing the Senate for the current Congress include a safeguard for the filibuster.

"They agree with President Biden's and my view that no Senate majority should destroy the right of future minorities of both parties to help shape legislation," McConnell said, suggesting that Biden has made his views clear behind the scenes.

McConnell's move means Biden doesn't have to start his presidency — won on a promise of unifying the country — by twisting Democratic senators' arms to amass the votes needed to jam a rules change down the throats of the minority party.

Few people are as familiar with the Senate, its rules on debate and the potential ramifications of changing them as Biden is. The threshold to overcome a filibuster was lowered from 67 votes to 60 votes in 1974, Biden's second of 36 years in the Senate. His knowledge of the chamber, and its prerogatives, is unusual in a modern president. Since 1974, when Richard Nixon resigned, the only other president who served in the Senate has been Barack Obama, and his tenure in the legislative branch was brief.

Former President Donald Trump's go-to tool on Capitol Hill was to bash senators of both parties from a Twitter account that has since been banned.

Download the NBC News app for breaking news and politics

Obama's approach to the Senate might be described as cool ambivalence. He often dispatched Biden to the Senate to negotiate the most politically tricky matters.

Now, Biden is helping the Senate run a very familiar play: the punt. More broadly, his handling of the issue allowed everyone to come out of the fight unscathed. McConnell lost on a firm commitment to entrench the filibuster, but it won't go anywhere without a major push from Biden.

It could be that gridlock entices Biden to flip against the filibuster later. In that scenario, it would be easier for him to argue that events justified killing it. Psaki's words carried the subtle threat that he could try to strip the filibuster from Republicans if they abuse it.

After all, Biden will have more influence with Manchin and Sinema for having stood with them now, and, as president, he will have a bully pulpit to stir up public pressure if he so chooses.