School districts and state governments across the U.S. are combating the worsening teacher shortage crisis that is expected to peak this school year with new creative policy solutions — and they're not exactly going by the textbook.

For its school year that began last month, Clark County school district, which has jurisdiction over nearly all public schools in Las Vegas, faced such a pressing shortage of special education teachers that it brought over 81 teachers from the Philippines.

"There is a shortage of teachers overall, and there is a crisis when it comes to the number of special education teachers available for hire," the district's chief recruitment officer, Michael Gentry, told NBC News.

That district isn't alone.

Experts expect teacher demand to exceed supply for grades K-12 in public schools by more than 100,000 for the first time ever — a dearth largely caused by endemic poor pay and the inability of districts to retain teachers.

The crisis comes as President Donald Trump has proposed slashing federal programs that help teachers and schools.

Local school districts and state legislators in the hardest-hit areas have taken matters into their own hands, experimenting with solutions that include hiking taxes to fund salary increases and importing instructors from foreign countries.

Sacramento public schools brought over 12 teachers to California from the Philippines, a mix of special education and science teachers, for the 2016-2017 school year and hired six more for the school year that kicked off last week.

"We searched locally to fill these positions, we searched throughout the state, and we had no choice but to start looking outside the country," said Alex Barrios, the district’s chief communications officer. "We just feel grateful we had this option available."

The Philippines has been an ideal country for schools facing shortages to turn to. Teachers in the country’s best schools speak fluent English (it’s one of the nation’s two official languages, stemming from its status as a former U.S. territory) and the national school system is similar to the American one, allowing teachers to more easily have their credentials and certifications transferred.

Both the California and Nevada districts went through AIC, a small San Mateo, Calif., placement agency, for their staffing needs.

The company’s CEO, Ligaya Avenida, said business has gotten markedly better over the past five years, as the national shortage has worsened.

Avenida, who was born and educated in the Philippines and who worked as a teacher and administrator in San Francisco public schools, said she helped recruit over 200 teachers from her home country for the upcoming school year — up from about 160 the prior school year and from 120 for 2015-2016.

The teachers come to the U.S. on J-1 visas, a nonimmigrant visa category designed to promote cultural exchange. It’s commonly used for foreign au pairs and camp counselors, according to the State Department.

Philippine teachers, who make on average between $5,000 and $7,000 annually, are lured by the higher salaries in the U.S.

The problem keeps getting worse

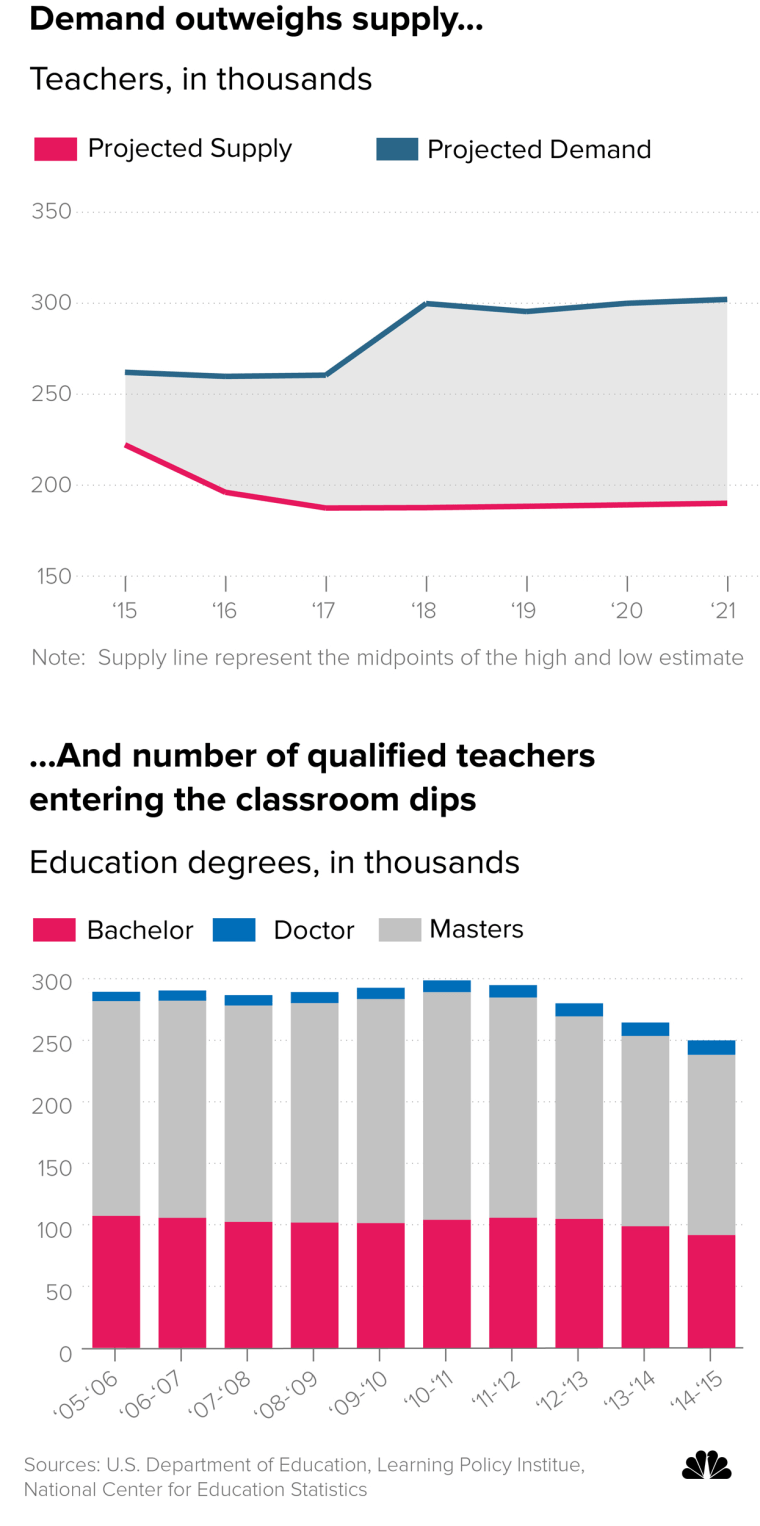

The number of teachers in demand has long exceeded the supply, but by most expert estimates the shortage will peak nationally in the 2017-2018 school year.

According to the Learning Policy Institute, an education think tank that analyzed federal education data, demand (nearly 300,000 positions public school districts need filled) will outpace supply (just over 196,000 teachers who are certified in their states are expected make up the teaching force) by more than 100,000 for the first time ever. (The data does not include teachers in private or parochial schools.)

The reasons for the crisis, which is expected to continue to worsen in coming years, involve problems with recruitment and retention because of low job satisfaction, with experts pointing to studies showing that more than two-thirds of those who leave the profession do so because they’re unhappy.

"The drivers of both recruitment and retention are pay and working conditions and the extent to which teachers are prepared and supported. We are doing worse in all three of those areas than we were in the early 1990s," explained Linda Darling-Hammond, the president of the LPI and a professor of education at Stanford’s Graduate School of Education.

"Pay is down, support is down and working conditions have gotten worse," Darling-Hammond said, pointing to findings of a 2016 study she co-authored titled "A Coming Crisis in Teaching?"

Solutions in the states

Over the last year, several states have attempted to ease those problems with legislation that increases teacher pay and provides funding for mentorship programs designed to retain good teachers.

The issue has largely brought Republicans and Democrats on the state level together to find solutions — a reprieve from the hyperpartisanship that has defined the current political climate in Washington and in many state capitals.

Arizona’s Republican Gov. Doug Ducey signed legislation in May that expanded an existing loan forgiveness program for teachers to provide added incentives for educators in low-income and rural schools.

South Carolina’s GOP-controlled state Legislature allocated $1.5 million for a rural teacher recruitment program for the 2016-2017 fiscal year.

In Nevada, the state’s Department of Education created a $9.8-million fund in 2016 to invest in professional development, leadership training and retention initiatives, while in Oklahoma, which has one of the most severe shortages in the country, Republican Gov. Mary Fallin has proposed budgets two years in a row that would give teachers a raise.

In addition, South Dakota’s Republican Gov. Dennis Daugaard and the state’s Republican-controlled Legislature approved a sales-tax increase in 2016 that was specifically used to pay for raising teacher salaries.

"People will go into teaching if it’s reasonable for them to do so financially," Darling-Hammond said.

The gold standard of policy would be legislation resembling a multi-faceted proposal being debated by Washington state legislators, which would increase teacher salaries, invest money in professional development programs, and provide loan-forgiveness.

In addition, the state’s Democratic Gov. Jay Inslee’s budget this year raised the minimum starting teacher salaries, with bonus potential for STEM (science, technology, engineering and math) educators. His budget also allowed individual districts to set their own teacher pay scales and to base them on local costs of living.

But, when it comes to to bringing over teachers from abroad?

It’s just a stop-gap measure, Darling-Hammond explained.

"It’s a temporary solution, a way to get teachers in the classrooms," she said. "What you really want to do is to build a strong, sustainable teaching force."