WASHINGTON — John McCain's legacy of bridging divides can perhaps be best understood by his efforts to help a Democratic president reconcile with Vietnam, despite McCain's own disabling injuries from years of torture in a Hanoi prison, and at a time when the political wounds of that conflict were still raw.

He did it with the help of a man he did not at the time either like or understand, a fellow senator who had fought in the war, and later protested against it.

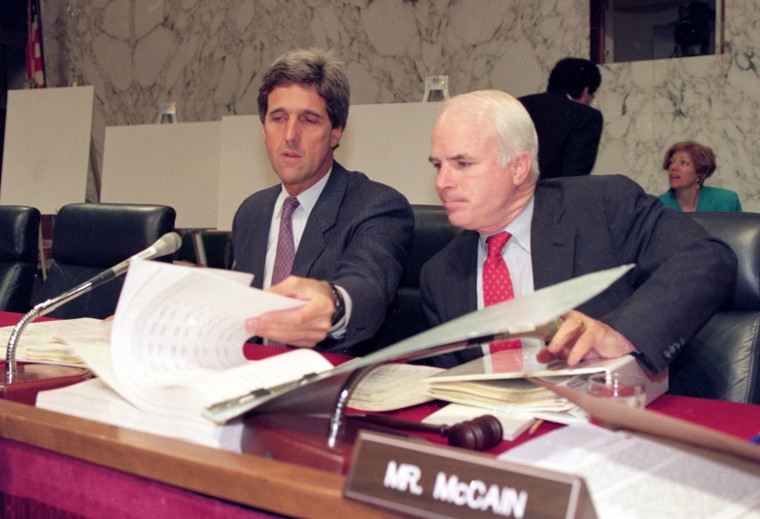

It was 1993, and McCain and John Kerry, two Vietnam veterans, had been working on a Senate committee to resolve the fate of prisoners of war and those missing in action from Vietnam. But their experiences and reactions to the war could not have been more different.

McCain heroically refused an early exit from prison because it would violate the military honor code of "last in, last out." And he wanted to deny the North Vietnamese a propaganda victory over his father, John S. McCain II, a four-star admiral then commanding all U.S. forces in the Vietnam theater.

Kerry, the angular Yale graduate, had returned from the war to testify against the conflict before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee in 1971, joining a protest of veterans who tossed their ribbons over a barricade at the Capitol during an anti-war rally. McCain, then still in prison, later said the North Vietnamese guards taunted the American POW's with accounts of that protest.

In a statement Saturday night, Kerry wrote, "We both loved the Navy, but had opposite views about the war of our youth. We didn't trust each other, but really, we didn’t know each other. After a long conversation on a long flight, we decided to work together to make peace with Vietnam and with ourselves here in America. In the process, he was savaged by lesser men, but words could never hurt a man who was, as Hemingway wrote, 'stronger at the broken places.'"

Their journey toward better understanding continued in Hanoi, on Memorial Day in 1993, during a visit to the "Hanoi Hilton," where McCain had been incarcerated and tortured for five and a half years.

Half a world away, on that same Memorial Day in 1993, President Bill Clinton — with McCain's encouragement — was trying to make peace with his own Vietnam history, a complicated one. During the 1992 Democratic presidential primaries, Clinton had been accused of dodging the draft, after the discovery of a letter he'd written in 1969 thanking the head of his Arkansas draft board for "saving him from the draft" with a student deferment.

Clinton was also the first president in decades who had not served in the military. Now, in office only four months, he was struggling to improve his relationship with the Joint Chiefs of Staff, deeply suspicious of his approach to the military. Trying to bridge the divide, Clinton decided to give his first Memorial Day speech at the Vietnam Memorial, despite threats from veterans groups to disrupt the event.

According to biographer Robert Timberg in "John McCain: An American Odyssey," McCain, hoping he could help head off such a confrontation, had written Clinton a letter offering to accompany him to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial.

Clinton declined the offer, but McCain made it public, eliciting considerable criticism from many of his friends in the POW community. The protestors showed up, and almost interrupted the speech. Twenty-five years later, it is hard to describe the ferocity of their anger as they tried to shout down the first president in decades who had not had military service.

Over the next two years, McCain worked tirelessly to smooth the path for Clinton to re-establish diplomatic relations with Hanoi. When the president finally announced the agreement to normalize relations with Vietnam in 1995, he was flanked by McCain and Kerry, his political wing men, giving him the cover to make peace with America's former enemy.

As Kerry wrote this weekend, "John McCain showed all of us how to bridge the divide between a protestor and a POW, and how to find common ground even when it was improbable." In Kerry's words, "John McCain was an American original — guts, grit, and ultimately grace personified."

The former POW's rapprochement with Vietnam is only one example of McCain's willingness to work with former rivals and embrace change.

As he said a year ago July in an impassioned farewell speech to the Senate, "We've been spinning our wheels on too many important issues because we keep trying to find a way to win without help from across the aisle."

And as he told Tom Brokaw last October, "You know the guy that I fought with and worked with almost more than anybody in the United States Senate was one Edward M. Kennedy. He and I would yell at each other. We would fight, we would and then we'd walk off and he'd put his arm around me and say: 'Hey we did pretty good didn't we?'

"That's the kind of relationship that you have to have and so we did a lot of legislation together and unfortunately unless you have that kind of relationship it's hard to really achieve results."

That's one more reason why his loss is felt so deeply. In today's Senate, John McCain may have been the last of his kind.