WASHINGTON — Chief Justice John Roberts could be in a position to reassert some degree of control on the Supreme Court in several race-related cases that may appeal to his vision of a “colorblind Constitution” when the justices return to action next week.

Three upcoming cases could see Roberts play a key role, showing that while the chief justice is not always the most influential voice on the 6-3 conservative-majority court, he is often in ideological lockstep with the five justices to his right. The court’s new nine-month term begins on Monday with newly appointed Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, the first Black woman to serve on the court, taking the bench for the first time and joining the liberal minority.

The notion that Roberts is no longer the dominant figure on the court is based on the view among experts that he is an institutionalist worried about the reputation of the court who does not want to move the law to the right on contentious issues as quickly or as boldly as some of his conservative colleagues. In June, Roberts did not join the majority in overturning the 1973 Roe v. Wade ruling that legalized abortion nationwide.

That decision showed the limits of his power to control the court’s direction now that he has five other conservatives to his right, including three justices appointed by former President Donald Trump.

The new cases on racial issues all ask the justices to adopt what challengers say are race-neutral approaches to the law, a line of argument that could appeal to Roberts based on his past votes and writings. If the court embraces those arguments, it would further weaken the landmark Voting Rights Act, end the consideration of race in college administrations, and strike down part of a law that gives preferences to Native Americans seeking to adopt Native American children.

“You could imagine this term giving rise to a narrative of the chief is back. I think that’s totally possible,” said Roman Martinez, a lawyer who served as a clerk under Roberts, referring to the new term as a whole.

The chief justice, appointed in 2005 by President George W. Bush, a Republican, has long argued that various government efforts to address historic racial discrimination are problematic and may exacerbate the situation.

“The way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race,” Roberts famously wrote in a 2007 ruling in which the court struck down a Seattle program aimed at desegregating schools.

He expressed a similar sentiment in a 2006 redistricting case in which he disagreed with the court’s finding that Texas had unlawfully diluted the Latino vote in drawing electoral districts: “It is a sordid business, this divvying us up by race,” he wrote. As chief justice, Roberts was in the majority on both occasions when the court in previous cases weakened the Voting Rights Act, enacted in 1965 to protect minority voters.

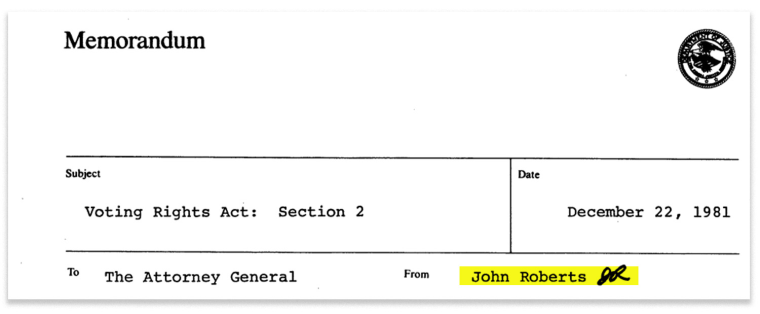

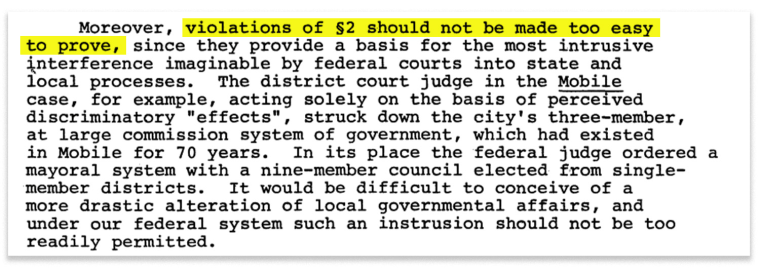

His approach to race issues dates at least to his time as an ambitious young lawyer in the Reagan administration. Then, he unsuccessfully advocated against legislation in Congress that lowered the barriers to bringing race discrimination claims under Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act. Such violations “should not be made too easy to prove since they provide a basis for the most intrusive interference imaginable by federal courts into state and local process,” Roberts wrote in one 1981 memo.

The same provision is at the center of the case that will be argued before the court on Tuesday. It concerns Republican-drawn congressional districts in Alabama, which challengers say unlawfully dilute the Black vote by drawing only one district out of seven in which Black voters are likely to be able to elect a representative of their choosing.

Alabama is urging the justices to adopt a legal test in which states would be given more leeway to draw maps using what it calls “race-neutral redistricting criteria” without being in violation of the voting law.

For Roberts, a ruling in the state’s favor would be “consistent with his view of a colorblind Constitution,” said Franita Tolson, an expert on election law at the University of Southern California Gould School of Law. “That would be devastating for minority voting rights in this country,” she added.

Conservatives have long opposed affirmative action, or the use of racial preferences, in college administrations. The Supreme Court has on several occasions narrowly upheld the practice, most notably in 2003. The justices are hearing two cases on Oct. 31 on the same issue concerning the admissions policies at Harvard University and the University of North Carolina.

The cases, both brought by Students for Fair Admissions, a group that opposes affirmative action, argue that policies aimed at promoting diversity on campus discriminate against white and Asian students by violating Title VI of the Civil Rights Act, which prohibits race discrimination in education and, when state universities are involved, the U.S. Constitution’s 14th Amendment guarantee of equal protection under the law.

The group’s lawyers say in court papers that both universities, which say affirmative action is essential to ensuring diversity on campus, ignore “race-neutral alternatives” that would still achieve that goal.

The case on Native American adoptions, being argued on Nov. 9, is a challenge to provisions of the Indian Child Welfare Act, a 1978 law enacted to retain the fabric of Native American communities by helping to keep adoptees within their communities where possible. The state of Texas, one of the challengers, said in court papers that the law features an “overt race-preference regime” by giving priority to Native American prospective parents.

It remains to be seen if the Supreme Court will view it as a racial issue. Several tribes and President Joe Biden's administration, which is defending the law, say the preference language focuses on Native American tribal affiliation, not race.

‘Unusual and difficult’

The court will tackle other contentious issues in the coming months, including a new clash between conservative Christians and LGBTQ rights in which a web designer wants to turn away people who ask her to create a website for same-sex weddings. She objects to expressing sentiments with which she does not agree, saying it violates her free speech rights under the Constitution’s First Amendment.

The justices are also hearing an elections-related tussle in which Republicans are seeking to limit the power of state courts to review gerrymandered maps and restrictions on voting. The court’s ruling in the dispute over Republican-drawn congressional districts in North Carolina could have big implications for the 2024 presidential election.

Those cases will further test Roberts’ leadership, with the chief justice in recent public remarks eager to show a return to normality after last term’s leak of a draft of the abortion ruling that led to protests and the construction of security fencing around the building.

In comments on Sept. 9, Roberts rejected claims that the court faces a legitimacy crisis. He expressed hope that the last term was an “unusual and difficult” one-off and that the new one would be relatively low-key.

“The more normal the better,” he said.

Irv Gornstein, executive director of the Supreme Court Institute at Georgetown Law Center, said the term is indeed likely to be less climactic than the last one simply because abortion is not on the docket.

But, he added, “I doubt it will be drama-free.”