WASHINGTON — The U.S. Supreme Court seemed inclined Monday to let iPhone users sue Apple by claiming that the App Store amounts to a monopoly that jacks up prices.

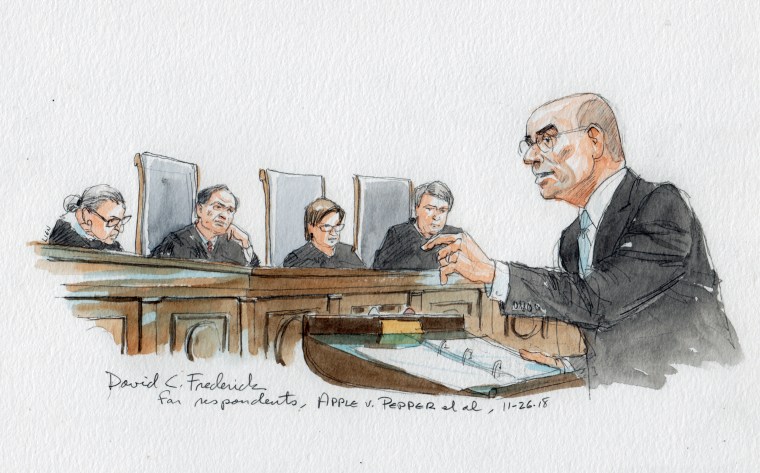

"Consumers pay Apple more than they would in a competitive market," said Washington, D.C., lawyer David Frederick, representing a group of Apple customers who filed a class action lawsuit. "You pay more than you would if there was a discount apps warehouse."

The Supreme Court must decide if antitrust law allows them to carry on with their case.

Apple iPhones are designed to run only programs sold through its App Store. When software developers offer their products, Apple reviews them for compatibility and malware and, once they are approved, charges the developer a 30 percent commission. When a customer buys an app, Apple collects the purchase price, if any, and sends the proceeds to the developer.

"It's a closed loop," said Justice Sonia Sotomayor, who appeared to side with the customers. "They claim the harm is the suppression of a cheaper price."

If the justices allow the case to go forward in the lower courts and Apple eventually loses, that could disrupt the App Store. Even though the average price of an app is just over one dollar, the App Store generated an estimated $11 billion in revenue for the company in 2017. A ruling that Apple was running an illegal monopoly could expose it to millions of dollars' worth of damages.

Software developers say that outcome would disrupt similar online marketplaces that operate between app creators and customers. But some consumer groups say it could create competition that would lower prices.

Apple urged the Supreme Court to throw the case out, arguing that it's not actually selling anything but is instead operating a marketplace that allows app developers to sell their products.

"The App developers set the price, and even if Apple raised the commission, there'd be no overcharging unless the developers raised their prices," said David Wall, representing the company.

For 40 years, the courts have held that when there's an illegal monopoly, only the direct purchaser can sue for damages. Suppose, for example, that the only supplier in town for dry cleaning chemicals is overcharging. Under this long-standing legal doctrine, customers who bring in their laundry cannot sue. Only the dry cleaners can, because they're the direct buyers of the chemicals.

As Apple sees it, even if the App Store amounted to an illegal monopoly — and the company insisted it isn't — only the app developers could sue under existing antitrust law, because they're the actual buyers of Apple's distribution service.

But Justice Neil Gorsuch suggested it might be time to overturn that the legal precedent that Apple depended on, something 30 states have already done. The Apple customers are suing in federal court, where the precedent remains valid.