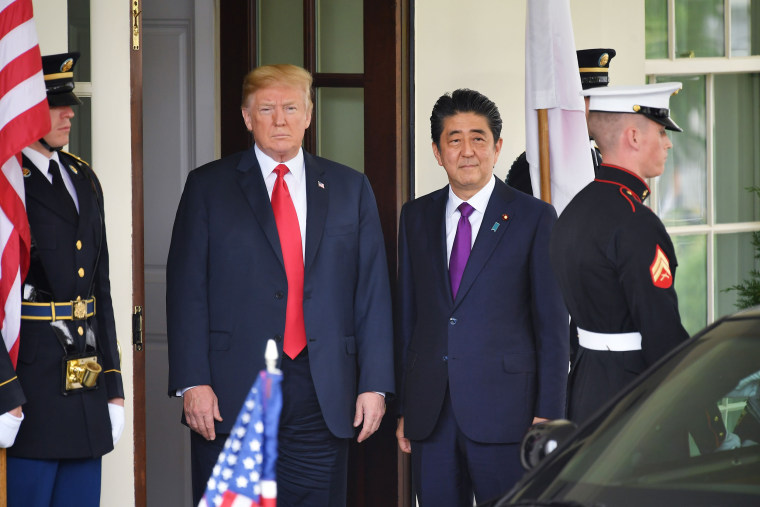

When President Donald Trump and Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe held a joint press conference at the White House last week, the two leaders spent several moments discussing an issue Japan cares about deeply but that has barely registered in American politics: the return of Japanese citizens who were abducted by North Korea.

The matter is part of a tense and painful chapter in relations between Pyongyang and Tokyo that many people in Japan are still grappling with.

Trump said he would follow Abe's wishes and bring up the issue during his Tuesday nuclear summit in Singapore with North Korean leader Kim Jong Un.

WHAT ARE 'THE ABDUCTIONS'?

From 1977 to 1983, several Japanese citizens living in coastal regions disappeared under strange circumstances. For years, rumors flew across the country that some of these citizens had been abducted by North Korean agents as part of a broader espionage campaign out of Pyongyang.

In 2002, Kim Jong Il, as part of a broader set of negotiations between North Korea and Japan that would produce the Pyongyang Declaration, admitted that members of the North Korean regime had abducted 13 Japanese residents.

The Japanese government maintains that 17 of its citizens were kidnapped and claims there are another 883 missing persons cases in which North Korean involvement cannot be ruled out.

Experts and historians have pointed out that Kim did not explicitly say that the abductions were part of a specific North Korean government campaign, but, rather, were the efforts by a small number of rogue actors within the government. The abductions would have all occurred during the reign of his father, Kim Il Sung, who led North Korea from 1948 until his death in 1994.

In addition, more than 3,800 South Koreans have been abducted by North Korea since 1953, according to advocacy groups for the families of South Koreans and Japanese abductees. More than 480 are still being held in North Korea, the groups say.

And abductions aren't the only human rights abuses carried out by the reclusive regime. North Korea, one of the most brutal and repressive governments in modern history, has committed "unspeakable atrocities" reminiscent of Nazi Germany, according to a 2014 United Nations investigation, including the murder, torture, rape, starvation and forced labor of its own citizens.

WHY DID NORTH KOREA DO IT?

While Kim apologized for the abductions, he did not disclose why they had taken place.

Experts on North Korean and Japanese politics, however, say the abductions were part of an effort by Pyongyang intelligence operatives to learn more about Japanese culture to better train its government spies to act and travel like Japanese people.

"The regime was using these Japanese nationals to train North Korean spies to act like Japanese people when they took part in overseas espionage activities," John Park, the director of the Korea Working Group at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, told NBC News. "For better cover stories. How they acted, how they traveled, pop culture references, language."

Jim Schoff, a senior fellow within the Asia Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, said many of the people abducted were also forced to teach Japanese language and culture to other North Korean intelligence agents and state-sponsored terror groups.

For example, a Korean spy convicted of bombing a South Korean passenger jet in 1987, killing all 115 on board, said she had been trained by Yaeko Taguchi, another Japanese woman who was kidnapped in 1978.

While there had been a substantial population of Japanese living within North Korea at the time, Schoff, who has written extensively on Japan and the Korean Peninsula, explained that Pyongyang felt it needed new people to "help their operatives from having their knowledge of Japanese culture go stale."

WHAT BECAME OF THEM?

In September 2002, as part of talks with Japan on the issue, North Korea admitted that, of the 13 people it claimed its government abducted, four were alive, eight had died and one's entrance into North Korea could not be confirmed.

Then, in October 2002, North Korea allowed five Japanese citizens it had abducted to return to Japan, where they were reunited with their families after nearly 20 years and in some cases longer. Under the agreement, according to the government of Japan, the five people had the option of returning to North Korea but decided to stay in Japan.

North Korea also turned over to the Japanese government the remains of the eight people it said had died. The Japanese government, however, has maintained that DNA testing showed that the remains did not in fact belong to the deceased abductees.

That included the remains purportedly belonging to Megumi Yokota, who was just a 13-year-old girl walking home from badminton practice after school when she was kidnapped in November 1977. She is perhaps the most well-known abductee and has become the face of the issue in Japan.

North Korea has claimed Megumi killed herself in 1994, but the cremated remains sent back to Japan in 2002 did not match her DNA, according to Japanese officials.

Megumi's family believes she is alive and has campaigned publicly for years for her return. Megumi reportedly married and had a daughter while living under the totalitarian regime. Her husband has reiterated Pyongyang's assertion that she died, but the family believes the statement was made under duress.

Megumi's story has emerged as a cause célèbre in Japan, and, Trump, during his 12-day visit to Asia last November, met with her family, as well as the families of other abductees. Barack Obama met with the family in Japan during his presidency, while George W. Bush hosted her family in the Oval Office in 2006.

WHAT COULD HAPPEN AT THE SUMMIT?

On one hand, experts say, Japan wants closure on this chapter in its recent history. Megumi's parents maintain their daughter is still alive and want her returned. And the families of other abductees, who North Korea claims are deceased, want proof of what happened to their loved ones.

On the other hand, with the prospect of a denuclearized North Korea on the table, the issue has reemerged as a key point in negotiations for Japan, which like several other nations, has begun exploring the terms of how to normalize relations with Pyongyang after a decadeslong freeze.

When Japan officially normalized relations with South Korea in 1965, Japan paid Seoul, as part of the deal, millions of dollars in aid and reparations (which stemmed from Japan's imperial history on the Korean Peninsula).

According to Schoff and Park, North Korea wants a similar deal as part of any normalization talks that would hypothetically follow denuclearization.

But Japan wants something, too.

"As part of a broader deal, Japan wants total satisfaction on the abduction issue, which of course, is a terribly important domestic political imperative," said Schoff, of the Carnegie Institute.

Abe, however — unlike Trump and the leaders of China and South Korea — has not yet had a bilateral meeting with Kim. As a result, Abe wants his goal articulated to Kim by Trump.

"He basically told Trump, 'When you see this guy, you tell him we haven't forgotten about this,' and, 'We're not going to support the normalization process and economic engagement process until we see this issue resolved to our satisfaction,'" Schoff said.