LONDON — Along the southern coast of England on Wednesday, President Donald Trump helped commemorate the 75th anniversary of the launch of the D-Day attack on Germany — the most celebrated maneuver in Western democratic military cooperation, and a turning point that led to the demise of the hyper-nationalist Nazi empire.

Back home, at the same time, the insider political news outlet Axios reported that his campaign planned to hit former Vice President Joe Biden, the leading Democratic presidential contender, as a "globalist."

The tension in Trump — seemingly eager to buff his credentials as a bare-knuckled nationalist after rubbing elbows with royalty and celebrating multilateralism — reflected the much deeper crisis confronting leaders on both sides of the Atlantic.

For many European officials, the new nationalism is that crisis.

Queen Elizabeth II, who has reigned since 1952, hinted at the fraught nature of the moment diplomatically as she toasted Trump on Monday at a state dinner at Buckingham Palace.

"After the shared sacrifices of the Second World War, Britain and the United States worked with other allies to build an assembly of international institutions, to ensure that the horrors of conflict would never be repeated," she said. "While the world has changed, we are forever mindful of the original purpose of these structures: nations working together to safeguard a hard-won peace."

The question facing voters and political leaders is whether the people of their respective countries are better served by a model of interdependence — featuring collective security, a shared (if evolving) culture, and relatively free trade and movement — or one that emphasizes the strength of individual states, defined first by strong national borders, unique cultures and self-determination.

While the past is not always predictive, there are obvious risks to a European continent full of competitive states with nationalistic tendencies.

"Nationalism, and its embrace by rulers and policymakers in Europe up through World War II even in nondemocratic polities, pushed leaders toward policies that made war more likely," Walter Russell Mead, a distinguished fellow in strategy and statesmanship at the Hudson Institute, said in testimony before the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence in 2014.

And yet it is undeniable that many voters have felt a profound sense of loss because of, or at least alongside, the fortification of intergovernmental relationships. Trump has pushed, with some effect, to get NATO countries to put more of their budgets into defense spending as a means of reducing the burden America shoulders as part of the alliance.

For the U.S., the money is relatively small, but the president clearly believes the principle and political value are worthwhile.

The United States and the United Kingdom have witnessed similar popular backlashes against internationalism — and to some degree multiculturalism — in recent years, turning toward stronger national sovereignty, against alliances perceived to be disadvantageous and, in some cases, against certain minorities.

In America, that meant the ascent of tea party Republicans and Trump, who campaigned on an "America First" platform that included ripping up and renegotiating trade deals, threatening to pull out of NATO, banning Muslims from entering the United States and ending illegal immigration.

Three years ago, shortly before Trump was elected, British voters opted to leave the European Union, a powerful economic partnership that has reinforced the security blanket of NATO. Similar to Trump, successive leaders of the U.K.'s ruling Conservative Party have tried to crack down on illegal immigration. Outgoing Prime Minister Theresa May has been a vocal critic of anti-Muslim bigotry but has been criticized for suggesting terrorism could be countered with education in "British values."

There is no conflict between the celebration of the defeat of Nazi nationalists and the resurgence of nationalism in Western democracies now, said Liah Greenfeld, a Boston University professor and author of the book "Nationalism: Five Roads to Modernity."

"I do not see much irony in that at all," Greenfeld said in an hourlong telephone interview with NBC News. "There is a huge difference between what we see now and what we saw then, which goes back to the nature of nationalism itself."

The basic concept, which she traces to the elevation of common folk to positions of power after the War of the Roses eradicated the English aristocracy in the late 15th century, allowed for the people to think of themselves, for the first time, as members of an elite with their own proud identity.

In England, and later in the United States, nationalism expressed itself in the development of equality, popular sovereignty and individual freedom. During the French Revolution, nationalism manifested as democratic authoritarianism and the Reign of Terror. Nazism, the most extreme brand of nationalism — one defined in large part by a belief in racial superiority and a desire to dominate the world — also resulted from democratic elections.

Steve Bannon, a former strategist for Trump who has tried to rally conservative nationalists in Europe, responded tersely to a question about what distinguishes the nationalism of Germany and Italy 75 years ago from the brand that's more en vogue now.

"Bullshit," he wrote in an email. "Imperial powers."

For Bannon, global influence involves the export and import of political ideology rather than the movement of armies across physical borders.

There's another important distinction, Greenfeld said, that gets lost when the word "nationalism" is thrown around in political debates.

"There is a lot of confusion today. First, people don’t realize that nationalism implies democracy and that this democracy can be both liberal and authoritarian," she said. "But without nationalism you don’t have democracy and they do not see any difference between racist and not-racist nationalism. The difference is tremendous. ... They should not be at all confused, but they are all populist and they are all nationalisms."

Trump appears to have benefited from any lack of clarity about his brand of nationalism. He won the vocal support of many white nationalists during the 2016 campaign, even as he has claimed in the past to be unaware that anyone would take the term "nationalist" to connote any racial preference.

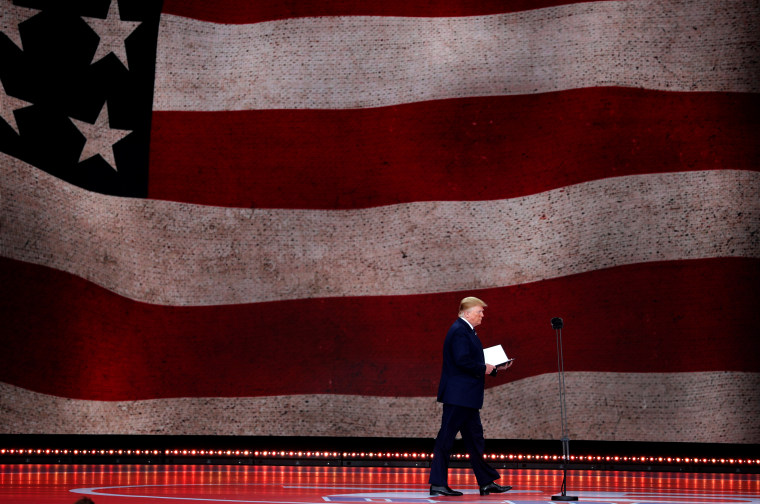

"You know, they have a word — it’s sort of became old-fashioned — it’s called a 'nationalist,'" Trump said at a campaign rally shortly before last year's midterm elections. "And I say, really, we’re not supposed to use that word. You know what I am? I’m a nationalist, OK? I’m a nationalist. Nationalist. Nothing wrong. Use that word. Use that word."

Nigel Farage, the conservative leader of the Brexit Party who campaigned on behalf of Trump three years ago, once said nationalism is best served in moderation.

"I think nationalism is a bit like alcohol," he said. "A little bit of it actually seems to make the world a better place and makes people feel pretty happy and pretty good about themselves. Too much is disastrous and leads to negativity and perhaps possibly in very extreme cases even hatred."

And, like alcohol, the question of how much is too much varies by person and situation. But on the 75th anniversary of D-Day, displays of nationalist sentiment were limited to the preview of a line of domestic political attack.

Asked whether the 2020 campaign would indeed paint Biden as a globalist — in contrast to the nationalist president — Trump spokesman Tim Murtaugh declined to confirm or deny the Axios scoop. “We don’t discuss strategy,” he said in email.