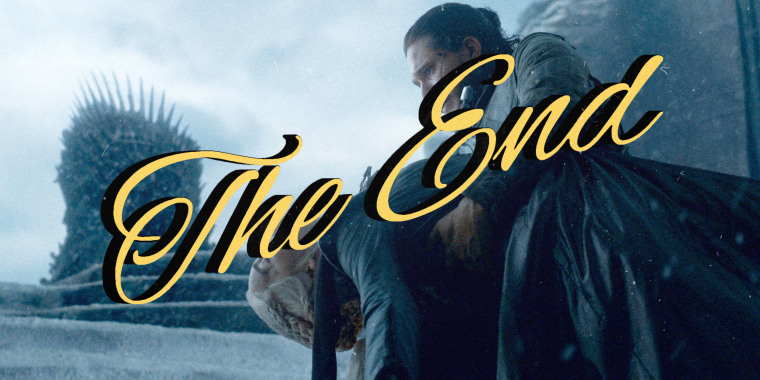

After eight seasons, lots of murder, wild conspiracy theories, and a couple of shots with accidental water bottles, "Game of Thrones" is over. For people who are sick of hearing their coworkers discuss Westeros on Monday mornings, it comes as a relief.

But diehard fans of the series had a lot of feelings to work through after the final episode Sunday. Between the shock, the praise, the memes, and the vindication for those who correctly guessed the ending, the prevailing sentiments about the finale seemed to be disappointment, and even anger.

The finale was bad, much of the Internet decided. In fact, the entire final season was under fire, as hundreds of thousands of people signed a petition asking HBO to remake the final season.

Now, "Game of Thrones" joins "Seinfeld," "Lost," and "The Sopranos" as the latest beloved show with a finale hated by most fans.

“When an invested fan's favorite show ends, they can feel a tremendous sense of agitation, loss or in extreme cases, even a loss of life purpose,” Dr. Laurel Steinberg, a New York-based fandom and relationship expert, told NBC News.

Steinberg said that the negative reaction can serve as a crutch for a person’s difficulty confronting the end of something that was a major part of their life.

“No matter their level of satisfaction with the plot’s outcome,” she said, zealous reactions can reflect a person’s “inner angst, turmoil, or general conflictedness about the show ending.”

Part of why people have such strong reactions is because dedicated viewers have “parasocial”— one-sided and imaginary — relationships with their favorite characters.

In a paper entitled “Parasocial Break-Up from Favorite Television Characters,” communications professor Jonathan Cohen of the University of Haifa studied 381 adults to understand how they process the loss of their favorite TV characters.

It turns out, Cohen found, viewers' reactions to TV weren’t so different from how they react to real-life relationships.

“If imaginary relationships with television characters fulfill attachment needs, then their breakup is likely to cause distress, especially among those viewers most vulnerable to separation anxiety,” Cohen wrote.

Cohen’s study showed these intense relationships don’t compensate for a lack of social relationships; instead, “parasocial relationships should be seen as an extension of viewers’ social relationships,” he explained.

If a show is done well, viewers should feel like they really know the characters they watch on their screens — they see them grow, change, evolve, and suffer. TV can make these relationships more intense than other mediums, because viewers follow characters for years, carve out time in their lives for them every week, and often watch them in intimate settings like from their couch or in bed, Caroline Framke, a TV critic at Variety, said.

When these relationship suddenly end, problems can arise because, as Cohen explains, “it is generally thought that parasocial relationships are functionally equivalent to social relationships.”

It’s possible, Cohen speculated, that "people simply have not developed separate ways of thinking about relationships that are imaginary rather than real.”

Steinberg agrees. “When people are invested in a show, they can feel as close, or closer to the characters as they do to their actual family members — they want them to end up safe, sound and successful.”

In this way, series finales can feel like breakups. All of a sudden, a major part of your life is no-longer. People get sad and angry. Steinberg said those feelings should be viewed as a “reflection of the intensity of the audience's affiliation with the characters and plot.”

And like in real life relationships, as a show comes to an end, viewers often seek closure.

"For a show you're really invested in and passionate about, whether you want to or not, you go into the end of it with a wish list," Framke said. If all your boxes aren't checked, "the gap between your desires and the reality can be really disappointing."

That’s the challenge of writing a finale. Everyone has their own idea of what they want from the conclusion.

Framke said the “Games of Thrones” finale was a “near-impossible task” to execute while pleasing viewers.

“I do think that series finales are incredibly hard, especially for something as big as ‘Game of Thrones,’” Framke said, adding that making everyone happy “should never be a creator’s instinct.”

"Games of Thrones," she said, felt urgent, partly because the fan base is so intense and because the show got ahead of the books on which it was based.

When “The Sopranos” screen went black in the finale, viewers were left scrambling, thinking their TV broke, and wondering what happened to Tony. When “How I Met Your Mother” stuck with an ending they had planned from the beginning, viewers felt disrespected, and didn’t think the ending matched the way the characters had evolved over the show’s nine seasons. When everyone found out Dan was Gossip Girl in the show's finale and Michael Bloomberg made a cameo appearance, viewers were just confused.

“All you can do for a good finale is be true to the story and acknowledge how the show has evolved,” Framke said, “The finales that don’t work are the ones that get too stuck — committing to an ending too early — or they feel like they have to tie up everything.”

If you think about it, it’s not terrible relationship advice either.