If the meltdown at Japan's stricken nuclear plant goes total, experts don't expect to see a "China syndrome" scenario or a Chernobyl-style conflagration. But the situation would be worse than it is now — which is why Japanese authorities have been working so hard to stabilize the situation at the Fukushima Dai-ichi complex. Emergency operations were briefly suspended on Wednesday, Japan time, due to a spike in radiation levels.

Just how much worse could things get? That's a matter of debate.

Princeton nuclear physicist Frank von Hippel suggests that we're already seeing the major effects of the meltdown, in the form of periodic releases of radioactivity from the reactors as well as from a fire-damaged storage facility for nuclear fuel rods.

"In a sense, the worst has happened already, with the fuel releasing much of its volatile radionuclides," von Hippel said today during an msnbc.com chat about the nuclear crisis. "The major danger from a meltdown would be a low-probability steam explosion if the molten core fell into a pool of water."

On the other end of the spectrum, a big explosion is exactly what Masashi Goto, a former nuclear design engineer at Toshiba, is worried about. During a Tokyo news briefing presented by the Citizen's Nuclear Information Center, which is generally critical of nuclear power, Goto said the molten core could spark a steam explosion ... or another hydrogen gas explosion like the ones that have rocked the reactor complex over the past few days. He said a full core meltdown could also set off a fresh nuclear chain reaction, much like the one that occurred in 1999 at Japan's Tokai processing plant.

"It could trigger the resumption of criticality," Goto said.

Experts on nuclear power say that the seriousness of the Fukushima Dai-ichi currently rates somewhere between Pennsylvania's 1979 Three Mile Island incident, in which the reactor's core melted down halfway but was kept contained within the facility; and the 1986 Chernobyl incident in Ukraine, in which a raging, uncontained fire spread radioactive contamination throughout Europe.

Japanese authorities estimate that 70 percent of the fuel rods are damaged at the complex's reactor No. 1, with 33 percent damage to the rods in reactor No. 2. The storage pool for fuel rods at reactor No. 4 has weathered two fires and an explosion, which apparently led to the release of radioactive plumes through gaps in the reactor building's walls. Meanwhile, water levels are reportedly dropping in other storage pools.

Water is the key

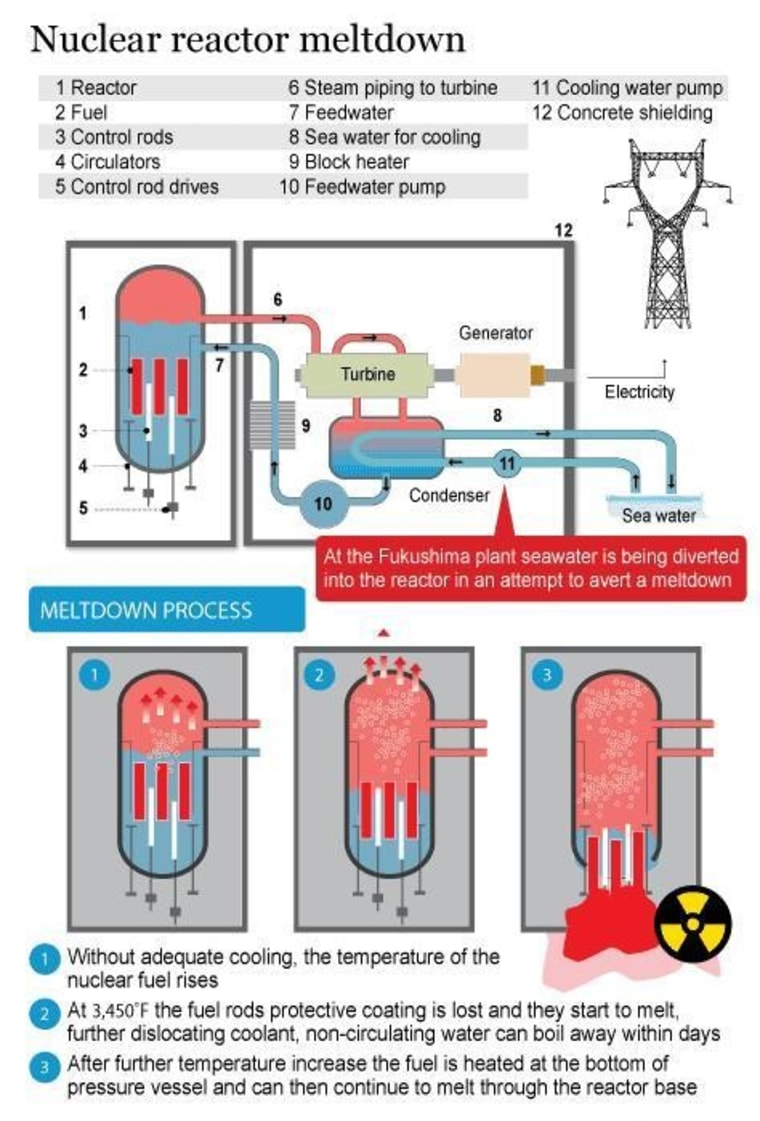

To head off further damage, Tokyo Electric Power Co. is talking about adding water and boric acid into the reactors and the storage pools, from helicopters as well as fire trucks. The water replaces the liquid that's boiling off because of the fuel rods' residual radioactive decay heat, while the boric acid helps slow down the nuclear fission rate.

Keeping the fuel rods covered with water is the key to heading off the worst-case scenario, said Elmer Lewis, professor emeritus of mechanical engineering at Northwestern University. "If you can keep any liquid at all in contact with them, they would probably not melt," he told me. Of course, you still have the problem of dealing with the radioactive steam released in the reaction. That's a problem the Japanese have become all too familiar with over the past few days.

"You don't want to be downwind, let's put it that way," said Norman McCormick, a professor emeritus of mechanical engineering at the University of Washington who is co-author of the soon-to-be-published book "Risk and Safety Analysis of Nuclear Systems." McCormick added, however, that the radiation risk would drop off sharply with distance.

"Dilution is the solution," he told me. "It's not a desirable thing, but it's the least undesirable thing."

Even under the best-case scenario, the messy cooldown process would have to continue for weeks. "It's going to be a long endgame, because they are going to have to keep cooling in there, and they will have to rig up something for the longer term," Lewis told Reuters.

The worst-case scenario

So what happens under the worst-case scenario? Let's assume for just a moment that fuel rods become exposed and go into full meltdown.

The fuel rods are actually long, hollow poles of zirconium metal, filled with pellets of uranium oxide fuel. That zirconium cladding is the first thing to go, melting at a temperature of about 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit (1,200 degrees Celsius). The uranium pellets' melting temperature is significantly higher — about 5,000 degrees F (2,800 degrees C). If the fuel pellets melt down, that creates a molten lava-like mess known as "corium."

Experts say it's possible for the molten core material to trap water in such a way to create a steam explosion, causing radioactive material to blast outward. That would be a bad thing, but as von Hippel noted, that's seen as a low-probability event. There's an even lower probability for a "China Syndrome" scenario, in which molten core material finds its way out of a reactor's container vessel and is released into the environment (supposedly falling all the way down to China, or in this case, New York). The reactors' containment shells are designed to catch the molten core material in a basin of steel, concrete and graphite.

But what if the containment shells have somehow become cracked or otherwise compromised, due to Japan's earthquake or explosions? "There's always been a debate within the technical community over whether [nuclear core material] can melt and mix with the soil," Lewis told me. "It's hard to model something that's never happened."

Physicist David Albright, a former U.N. weapons inspector who is now president of the Institute for Science and International Security, noted today on MSNBC that there's been a "slow bleeding" of radioactive pollution into the environment. The worst-case scenario, he said, would result in a release of radioactivity on a level that's "probably not as much as Chernobyl, but nevertheless a very significant release."

In the most extreme case, the Japanese might have to consider following the Chernobyl example and "dump sand or concrete on the open wound," Nathan Hultman, an energy policy expert at the University of Maryland, told me.

"We don't have a lot of experience with this," Hultman said.

The best-case and the worst-case scenario both end with years of cleanup and reconstruction, not only due to the nuclear crisis, but also due to the wider challenge of dealing with the other effects of the earthquake and tsunami. How will Japan cope? How will the wider world respond? Feel free to weigh in with your comments below.

More on Japan's crisis:

- Q&A: Clearing up nuclear questions

- Nuclear worries focus on spent fuel pool

- Robots to the rescue in Japan? Not yet

- Cosmic Log archive on the Japan crisis

- Special report on the disaster in Japan

Join the Cosmic Log community by clicking the "like" button on our Facebook page or by following msnbc.com science editor Alan Boyle as b0yle on Twitter. To learn more about Alan Boyle's book on Pluto and the search for planets, check out the website for "The Case for Pluto."