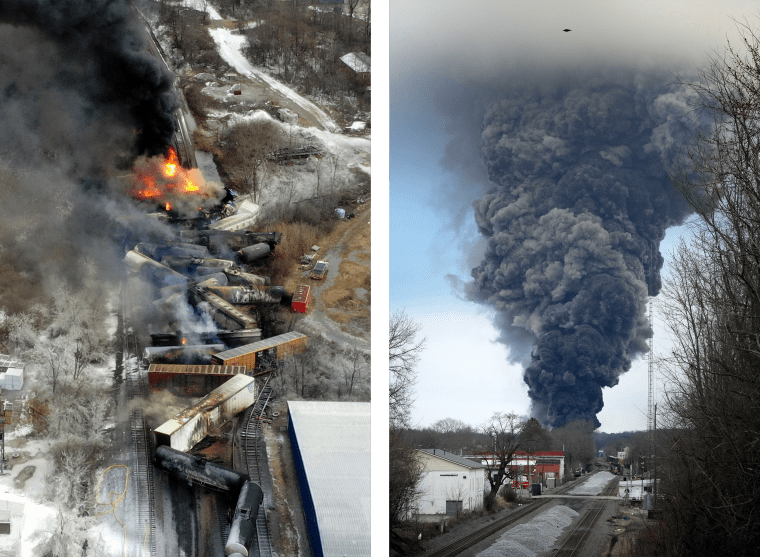

The sizzling wreckage of a derailed train. Toxic smoke pouring over a small town. Fearful residents fleeing their homes. The images of East Palestine, Ohio, could only be described as “déjà vu” for Bruce Bennett, a retired judge in Louisiana.

In darkness on the morning of Sept. 28, 1982, a train jumped its tracks and sent more than 30 tanker cars filled with hazardous chemicals or fuel crashing near a commercial strip of Livingston, Louisiana, about 20 miles east of Baton Rouge. Chemical leaks and smoke plagued the area for days.

“The cars were sitting there burning and smoldering, five, six days after the derailment,” Bennett said. “One of the cars just blew up. The damn thing went 600 feet in the air.”

Livingston’s derailment offers one of the closest parallels to the disaster unfolding in East Palestine. Both were major train crashes. Both involved some of the same chemicals, including vinyl chloride. Both communities saw train cars catch fire and chemical fires pollute the air.

And both communities have grappled with deep concerns about the safety of the air they breathe and the water they drink.

More than 1,000 train derailments happen each year in the U.S., according to Federal Railroad Administration safety data. Incidents involving hazardous materials are rare; railroads reported 12 hazardous releases in 2021.

Few have been as impactful as the one in Livingston, where cleanup efforts, health monitoring and water testing continued for at least three decades. It’s a situation that offers some sense of the future for residents in Ohio and also serves as a reminder that U.S. rail towns for decades have faced dangers as chemicals pass through.

In East Palestine, “a lot of things that have happened seemed eerily similar to what happened in Livingston over 40 years ago,” said Bennett, who as a local judge spent decades overseeing the aftermath of a legal settlement reached after the derailment.

The derailment and subsequent explosion stirred Livingston residents awake as it sent a fireball into the air that splintered a grove of pine trees and blew in the brick front of a nearby home. One Livingston resident had to jump from the window of a burning home and run to safety.

“We heard the roar,” said Jerry Cutrer, a businessman who lived less than a mile from the derailment. “It shook our house.”

The force cracked the foundation and burst the windows of the restaurant he owns, G&J Drive Inn.

“We loaded up and we got out of town,” Cutrer said.

About 2,700 people within 5 miles of the derailment evacuated at the behest of authorities. They left horses and pets.

Four days after the derailment, pieces of a train car exploded and rocketed into the air, smashing into a quadraplex building and setting fire to a mobile home, according to a National Transportation Safety Board report. Residents couldn’t return for about two weeks as chemicals within the train cars continued to explode, burn and seep into the ground.

In the end, 19 homes or other buildings were destroyed or severely damaged. About 200,000 gallons of chemicals spilled and were absorbed into the ground.

The NTSB found that members of the train crew had been intoxicated and drinking before the derailment. An untrained clerk had been at the train’s controls.

The derailments in Livingston and East Palestine share several parallels.

In Livingston, 43 of the train’s 101 cars jumped the tracks, including more than 30 carrying hazardous or flammable chemicals. In East Palestine, 38 of the train’s 151 cars derailed, including 11 with toxic chemicals.

Both trains were carrying vinyl chloride, a colorless flammable gas used to produce polyvinyl chloride (PVC) plastic. The chemical can cause disorientation, numbness and nausea, among other short-term medical concerns. It’s also a known carcinogen. Both trains were also carrying ethylene glycol, which can cause a sore throat and nausea at high concentrations.

In both locations, officials decided to vent and burn vinyl chloride to prevent more explosions, a process that polluted the air with toxic smoke.

“Some people complained of nausea and headaches,” Cutrer said of Livingston. The same has been true in East Palestine.

Wary residents in both towns turned to bottled water as officials scrambled to reduce the risk that hazardous materials would contaminate groundwater.

“They were very upset. They were having meetings all over the place,” Cutrer said of Livingston residents. “Air quality and water — that’s what the conversations were about. They were afraid to drink the water.”

Earlier this week in East Palestine, Gov. Mike DeWine and Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Michael Regan drank the local tap water in public to assure residents it was safe.

That demonstration only proves the water is safe to drink today. Regular water monitoring, something implemented for decades in Livingston, will be needed, said Abinash Agrawal, a professor of environmental sciences at Wright State University in Ohio.

“We don’t know how much vinyl chloride seeped into the ground,” Agrawal said. “Once it gets into the ground, it will travel.”

Agrawal said it could take months or longer to create a detailed, three-dimensional map of where the toxic chemicals entered the ground and if and how they’re spreading at the East Palestine site. It’s possible that seeping chemicals could travel toward East Palestine’s public well sites, Agrawal said, adding that more data and field evidence are needed to evaluate that risk to drinking water. Cleaning a contaminated aquifer could take five to 10 years, Agrawal said.

Years of environmental testing and legal wrangling likely lie ahead. At least 14 lawsuits have been filed over the derailment impacts in the East Palestine area.

In the weeks after the Livingston derailment, local attorneys filed a class-action lawsuit against Illinois Central Gulf Railroad, according to Calvin Fayard Jr., an attorney who led the coalition.

The class action, which was settled in 1985, ultimately guided the cleanup and recovery process and reshaped the town. The $39 million settlement paid out more than 3,000 residents, created a commission to make decisions about the recovery and set aside funds to pay for long-term impacts.

The settlement provided funding for 30 years of regular water monitoring and established a fund to maintain a health clinic in Livingston, where residents could get a physical and blood testing each year for contaminants. The clinic remains standing.

Some damages were handled separately. A jury awarded nearly $3 million to Terry Wisner, a state police officer who responded to the derailment and later developed headaches, difficulty swallowing and shortness of breath. Wisner retired at age 38 due to his symptoms.

The town’s environmental recovery became a prolonged affair.

As part of the remediation, workers dug out affected soil to a depth of 50 feet and replaced it, Fayard said. They also pumped out contaminated water. Additional remediation efforts against perchloroethylene, a solvent used in dry cleaning, continued into the 2010s.

Aside from cases involving first responders, Bennett said he was not aware of lawsuits in which Livingston residents years later claimed that long-term health problems stemmed from chemical exposures. Testing never identified specific concerns, though many residents skipped visits to the clinic.

“Taking that annual free visit for toxic monitoring just was not on people’s high-priority list,” Bennett said. “In retrospect, it would have been an outstanding opportunity for a long-term clinical study.”

Contaminants did spread gradually in the soil and groundwater, but within acceptable limits.

“There was concern it would bleed through different levels of aquifers,” Bennett said. “We never had evidence it entered into Livingston’s drinking water system.”

Cutrer said the emotional scars lasted at least a decade for his neighbors.

“Every time they heard a train go through, they’d think about it,” Cutrer said.

Fayard, who went on to represent dozens of other communities after derailments, is now working with East Palestine plaintiffs.

Today, a park sprawls over the derailment site in Livingston. JT Taylor, Livingston’s current mayor, said the settlement funding has helped the local economy and allowed for some investments the town might not have made otherwise.

“I see some positive things,” said Taylor, who was only 1 year old when the derailment shook his hometown. “Of course this is 40 years down the road. It’s hard to see that positive when it’s in your backyard today.”